Avoca, County Wicklow, Ireland

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz and may not be reproduced without permission

Avoca: A Cornish Mining Landscape in ‘The Garden of Ireland’

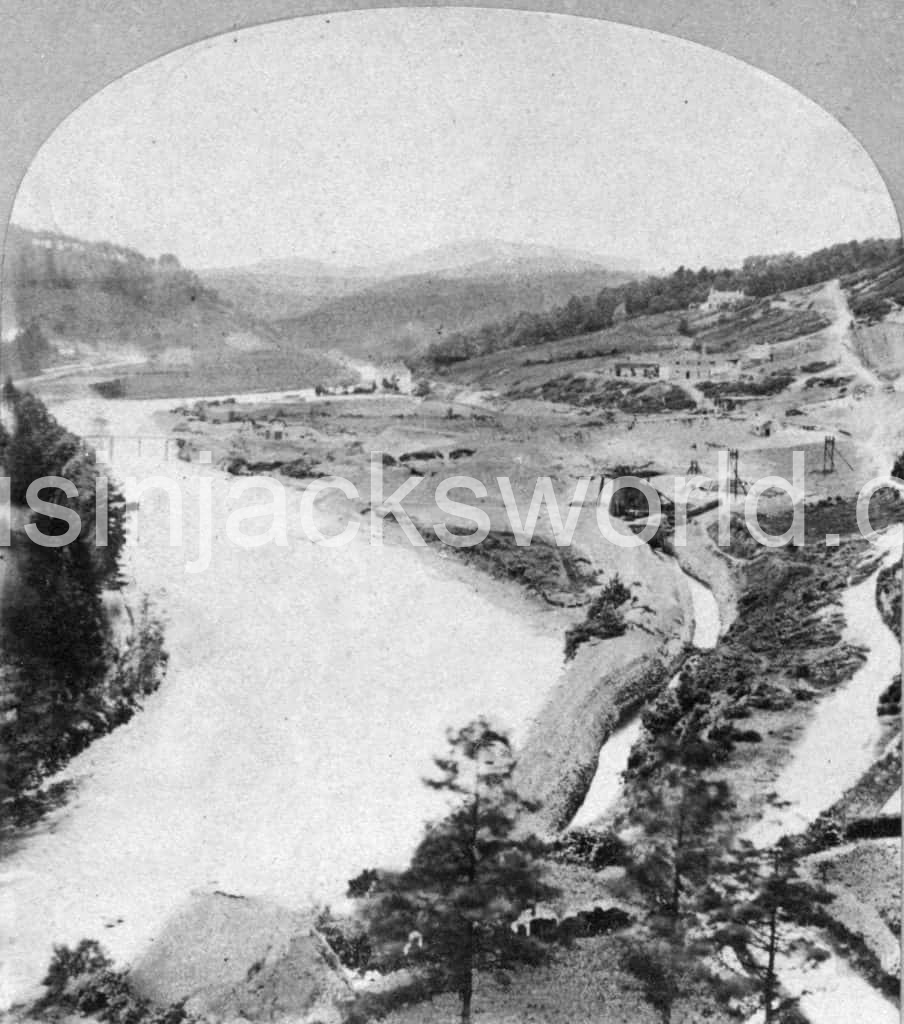

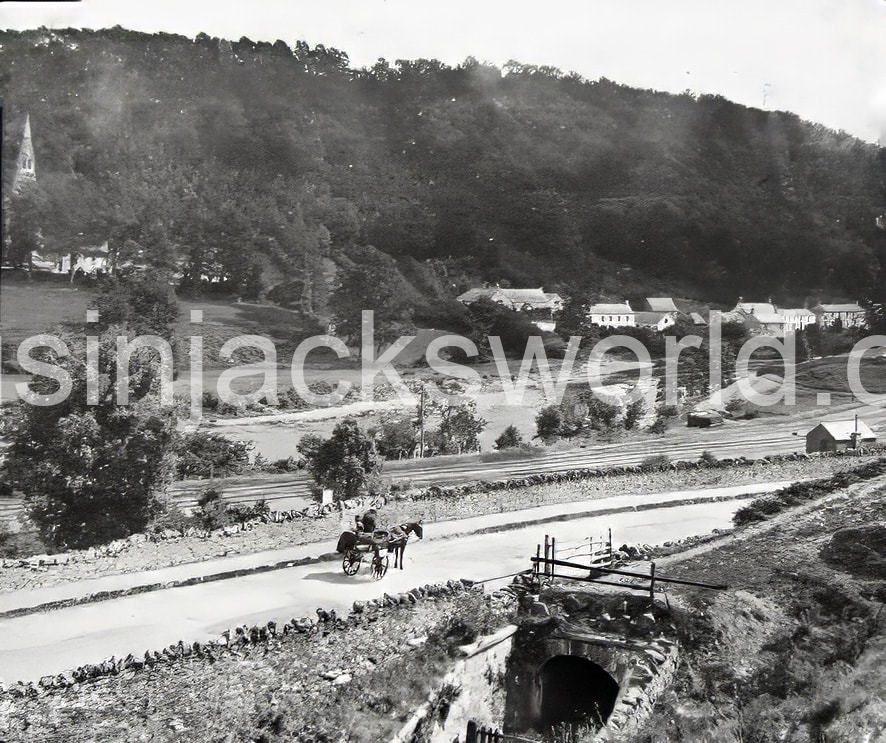

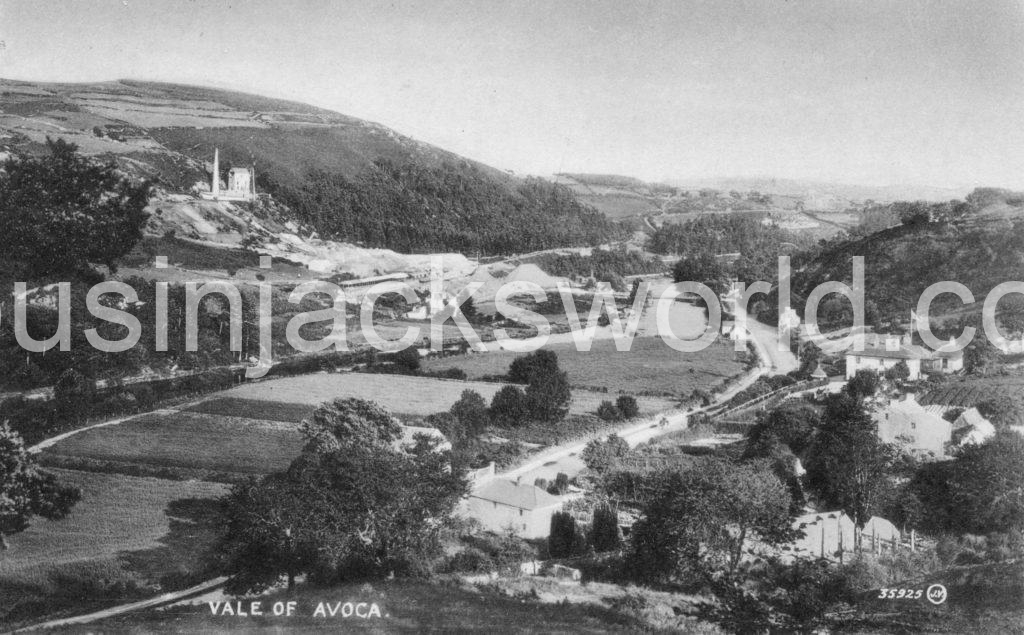

Made famous by the BBC TV series, Ballykissangel, the village of Avoca (Abhóca in Irish, and formerly known as Newbridge) is located some 55km south of Dublin. It lies in the eastern foothills of the Wicklow Mountains in County Wicklow, known as ‘the Garden of Ireland.’ The earliest verified documented history of metalliferous mining in the Avoca Valley, a mineralised area stretching for some 4km on both sides of the Avoca River, dates to the 1720’s. For the next two centuries, mining in Avoca flourished, triggered by the demands of the Industrial Revolution in neighbouring Britain.

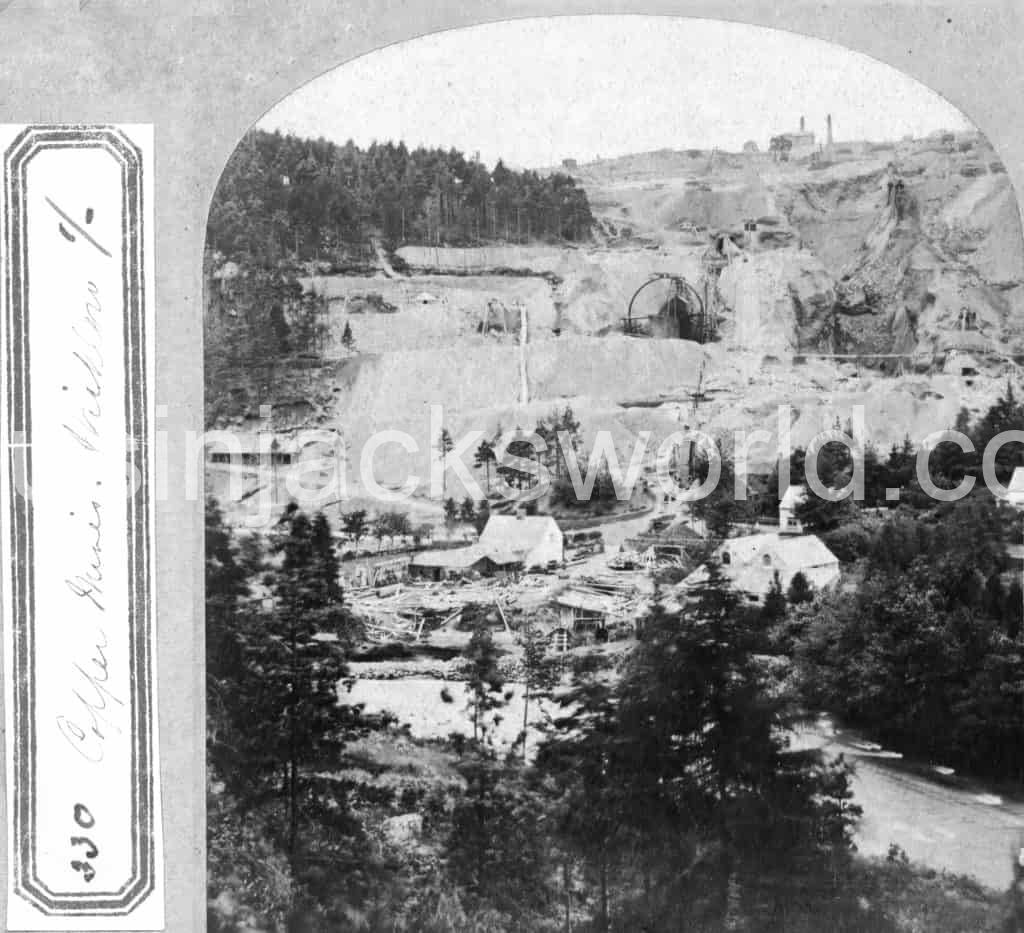

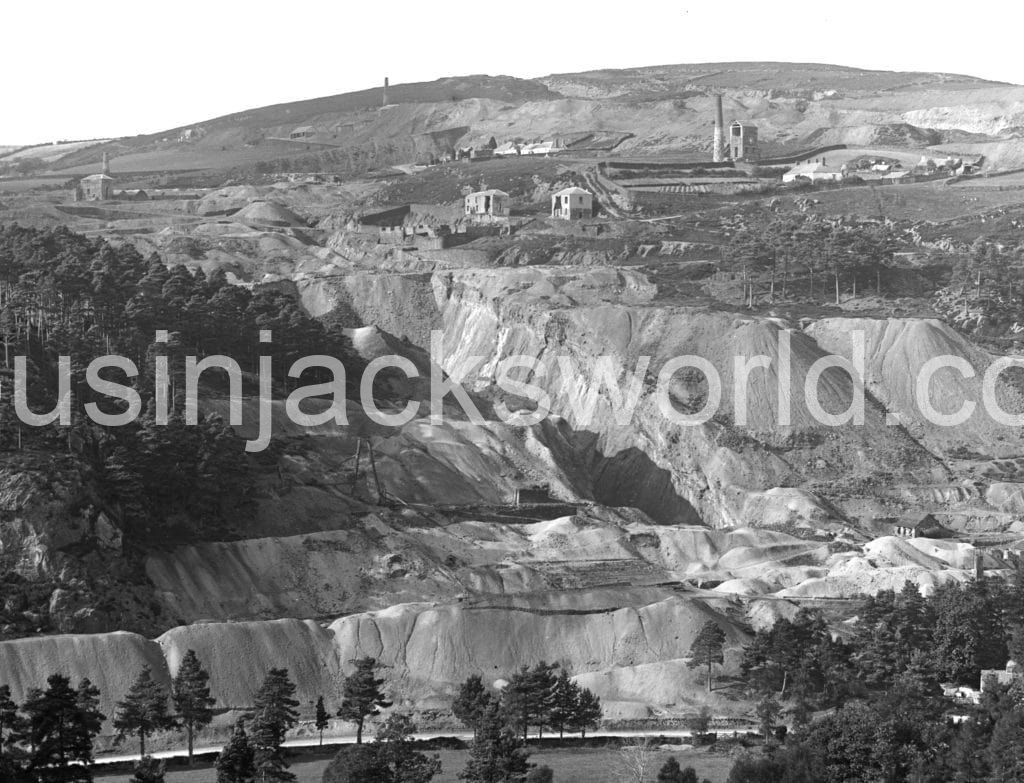

The mines of Tigroney, Cronebane and Connoree (Connary) on the east side of the river, and Ballymurtagh, Ballygahan and Ballymoneen on the west, were the most important group of metalliferous mines in Ireland. The exploitation of a variety of minerals, including copper, pyrite (sulphur), zinc and lead, resulted in rural industrialisation on a scale uncommon in Ireland. With the tips of attle (spoil), calciners, yards of launders, and forest of engine houses and stacks, Avoca was a mining landscape redolent of those in Cornwall. As many as nineteen steam engines were installed in the Avoca Valley at various times during the 1800s, most manufactured in Cornwall, including the largest engine ever set to work on an Irish mine.

Mining continued, with interruptions, until 1982. For three centuries, the Cornish played a significant role in Avoca’s mining industry.

Mining in the valley is undoubtedly of great antiquity, perhaps reaching as far back as the Bronze Age. Spectacular evidence for prehistoric mining has been confirmed across the Irish Sea at Parys Mountain in Anglesey, Wales, which shares identical geology with Avoca. The mineralisation at both sites is comprised of volcanogenic sulphide deposits emplaced on the sea floor during the closure of the Iapetus Ocean. Ptolemy’s map of Ireland in AD 150 includes ‘Oboka,’ suggesting that the Romans knew of the area, possibly due to its visible gossan outcrops.

Sparse texts attest to iron working at Avoca in the second century, and later in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when small-scale iron workings flourished across the eastern half of Ireland utilising gossans from Avoca, as well as other sources of ore. By the early 1700s, the iron industry was much reduced in Ireland, primarily due to the depletion of hardwood forests, the trees of which had been felled for the production of charcoal for smelting the ore.

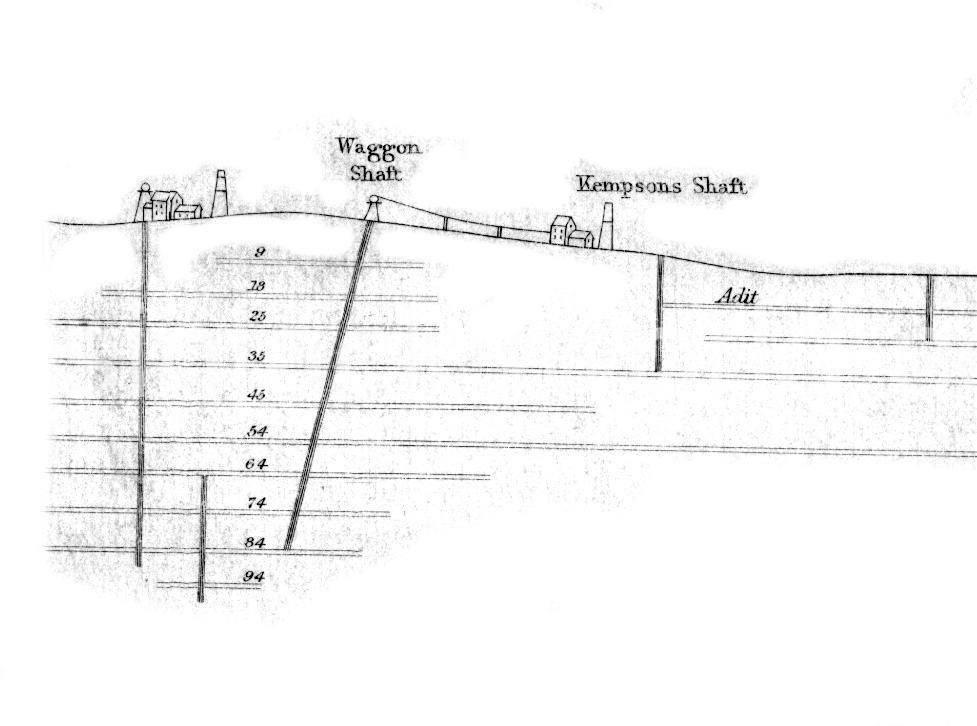

The first phase of verifiable exploitation for metalliferous ores at Avoca, which lasted until the late-nineteenth century, began in the early eighteenth century and consisted mainly of small-scale underground extraction of narrow high-grade copper veins yielding up to a few thousand tons of ore a year. This produced a warren of interconnecting shafts and levels throughout the Avoca area. Pyrite extraction became significant during the mid-nineteenth century, when 1.5 million tonnes was produced mainly from underground, but also from some surface workings. Twentieth century working switched from underground to open casting methods, creating huge excavations which can be seen today.

During the Victorian period, the Avoca Valley was lauded for its picturesque qualities, immortalised in the ballad by Thomas Moore written at Woodenbridge near Castle Howard, entitled The Meeting of the Waters:

“There is not in the wide world a valley so sweet

As that vale in whose bosom the bright waters meet“

Moore was here referring to the confluence of the Avonmore (Abhainn Mhór, Big River) and Avonbeg (Abhainn Bheag, Little River). But this narrative deliberately airbrushed out the tell-tale signs of mining degradation downstream, for as early as 1832 it was noted that the Avoca River which flows southwards to the fishing port of Arklow, had become so polluted as to decimate the salmon fishery.

Indeed, Avoca rapidly became the most significant mining area in the island of Ireland and its most visibly industrialised, as immortalised in the words of Sir Warington W. Smyth F.R.S, in 1853:

“There is, perhaps, no tract in the British islands which exhibits, even to the eye of the uninitiated, an appearance so strongly stamped with the characteristics of the presence of metallic minerals. For a considerable distance on both sides of the deeply-cut valley of the Ovoca the face of nature appears changed, and instead of the grassy or wooded slopes, or the gray rocks which beautify the rest of its course, we see a broken surface of chasms, ridges, and hillocks, glowing with tints of bright red and brown, or assuming shades of yellow and livid green, which the boldest artist would scarcely dare to transfer to his canvas. Here and there from among the ruins peers the white stack and house of a steam-engine; or water-wheels stand boldly projected against the hill-side, – some still and neglected, others whirling round in full activity; long iron pump rods ascend the acclivities to do their work at distant shafts, and as long as daylight lasts, the rattle of the chains for raising the ore, and the clink of the separating hammers attest the vigour of the operations.”

The sweet waters of Moore’s poem were heavily polluted with metals which had leached from the heaps of surface waste rock and from numerous adits draining the workings. In 1868 the Wicklow News-Letter reported that the river was ‘vitiated by the infusions of mineral poisons, destructive of all fish who enter it.’ In 1898 the same paper reported how the opening of the mines had destroyed the salmon and trout fishery that had developed in Arklow. The fish were poisoned by the river water that was:

“… charged with the particles of sulphur, iron, and copper degraded from the exposed lodes and heaps of mineral and refuse which had been raised. These then became and still remain fatal to the salmon and trout, so that when in the season the fish visit the river they do not—under normal conditions—survive for more than a couple of days, gradually becoming choked and weakening from the time they enter the harbour.”

The Avoca River is one of the most polluted waterways in Europe and acid mine drainage continues to be an environmental issue to this day.

Cornish Miners in Eighteenth Century Avoca

Cronebane was said to have been discovered in the early eighteenth century. By 1752, it was a substantial operation employing 500 men and in the ownership of Mr. Thomas Smith of Drumcree, Co. Westmeath. It was probably this mine that was the scene of a disaster in 1737, when eight men driving an adit were entombed by the collapse of ground. Only one of them survived. In 1756, Smith advertised the sale of all the royalties of the copper, lead and ochre mines, as well as the mineral water, on the ‘Lands of Cronebane and Tigroney, being the most remarkable Mine and Water in the Kingdom of Ireland.’ The present company had ‘about 15 years to come, paying the Landlord the Tenth Dish clear of all expenses and after the expiration of said Lease to be sold for ever.’

Smith also had a mineworking in the vicinity of Kilmacrea, and this is likely a reference to Connaree Mine which had also been worked by a former company, probably that active at Tigroney and Cronebane. Silver obtained there from the ochre and lead had sold well and the quality of the cupreous waters was most surprising, ‘it alone making fifty Tons of pure Copper yearly, at least.’

The Cronebane, Tigroney and Ballymurtagh Mines were purchased by William Johnson of Shillelagh near Carnew for a term of 61 years from 5th September 1757. In 1765, Johnson was anxious to sell shares in his mining concern, and as a result he leased the Ballymurtagh Mines for 31 years from 1st August 1759, but he reserved Cronebane and Tigroney. The Johnson family held these mines for close on a century.

By 1755 Ballymurtagh which had previously been rich but had undergone a period of closure, was being successfully worked by Smith for copper. In 1768 it was taken on by a man named Whaley and a smelting works was established in Arklow. Sometime prior to 1780, Ballymurtagh was acquired by John Howard Kyan, and in 1783 and 1785, he successfully sought parliamentary grants to implement the smelting of the ores, which was unsuccessful. He later came to a leasing agreement with Roe and Company who had a smelter at Macclesfield and had just lost their lease to mine at Parys Mountain. This company purchased the mineral rights of Tigroney and Cronebane and began operations. By 1787, they had over 100 men employed in East Avoca.

That year the company changed its name to the Associated Irish Mines Company (AIMC). It was primarily English-run, and involved Abraham Mills, William Roe, Thomas Weaver, Thomas Smith, Charles Caldwell and Brabazon Noble. After having done some work at Ballymurtagh, the AIMC ignored it much to Kyan’s annoyance. Kyan then formed a partnership with Turner Camac, Colonel John Camac and John Howard Kyan, styled the Hibernian Mining Company. Irish-run, it became a rival to the AIMC and both companies issued their own copper tokens, which are highly collectable today.

The first mention to the Cornish working at Avoca is in relation to cementation (a process in which water containing copper forms a deposit on iron). The waters of the Cronebane Mine were very rich in copper in solution, and according to Henry Kenroy writing in 1751, the process of cementation was accidentally discovered sometime around the mid-eighteenth century when an iron shovel had been left in a cupreous outflow.

However, evidence points to the fact that the knowledge of cementation was brought across from Cornwall, where the precipitation of copper from the salts contained in mine water had been observed at Chacewater Mine (Wheal Busy) in the early 1820s by John Costar, who was responsible for introducing an hydraulic engine into Cornwall. He made some experiments at Wheal Crofty soon afterwards, but the process never caught on in Cornwall.

Shortly after Costar’s discovery at the Chacewater Mine, a group of miners migrated from the mine to work at Cronebane. This was then under the management of Captain Thomas Butler of Redruth who had moved there with his wife, Constance Paynter and two young daughters, sometime after 1825 and before 1830, when his daughter Grace died at Newbridge. A Madam Butler’s Shaft and a Madam Butler’s Vein, the workings thereabouts noted by Philip Argall in 1879 to have been of great antiquity, are undoubtedly named for Captain Butler’s wife. At Captain Butler’s insistence, a chain of stone-lined oblong pits were constructed into which iron bars were placed onto suspended wooden beams to attract the copper. After frequent agitation by scraping, the iron was eventually dissolved, the water was turned off and the copper mud shovelled out of the pit to dry in heaps.

Cementation soon caught on in the neighbouring mines, where at Ballymurtagh in 1787 Captains James Jones and William Penrose (of Welsh and Cornish parentage) were experimenting with placing low grade pyritic ores into mine water, comparing the strength of the resulting cupreous liquid with that observed at Parys Mountain in Anglesey where the technology had been introduced. The unusual mineral properties of the waters from Parys Mountain had been known since the early seventeenth century, as a letter of Sir John Wynne of Guydir dated 1607 attests, although nothing beyond a few experiments had been undertaken at that time. Nearby Ballygahan had decided to calcine the ores prior to washing, and the water from the washing floors was directed into settling pits and then run onto iron scrap. Cronebane’s copper pits were noted to have been making copper well in September 1787.

Above £12,000 worth of copper had been obtained by the cementation at Cronebane, and the resulting precipitate was shipped from the Port of Wicklow to Macclesfield and later Liverpool for smelting. Cornishman, Captain James Treweek of Gwennap, managed the Mona Mine at Parys Mountain where cementation had been introduced from the Wicklow copper mines, and his son took this technology to the El Cobre mines in Cuba. From Cuba it was ‘reintroduced’ to Cornwall in 1854 (where it had never been turned to practical account), by a return miner who set up plant on the Great County Adit in Gwennap.

But the precipitation of copper salts was not novel. Cementation had been practised in mining areas across Europe working suphuritic ore bodies from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including Agordo in Italy, Waldeck in Germany and Rio Tinto in Spain. What is beyond doubt is that Cronebane Mine witnessed the first practical application of this process in Britain or Ireland.

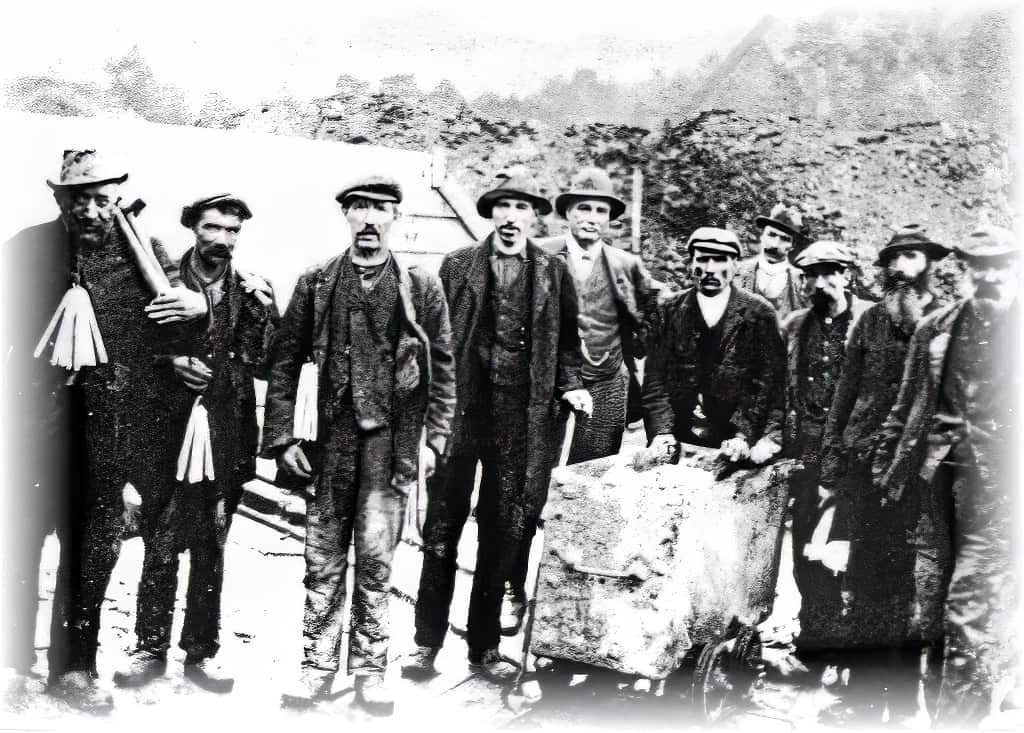

Numerous Cornishmen were working for the English-backed AIMC in the late eighteenth century, for at Cronebane in August 1788 a bargain was noted as let to three Cornishmen at a high rate who had recently arrived in Avoca. The mines were being worked Cornish fashion, on tribute and tutwork. Names that appear in the contemporary cost books of probable Cornish derivation include Bailey, Bamfield, Bennett, Carew, Daniel, Harris, Harvey, Hill, Holman, Laity, Martin, Mitchell, Paul(l), Penrose, Tonkin and Vivian. One of them, Nathaniel Holman, appears to have been from Gwennap Parish.

Trouble broke out when the Cornish miners expected subsist as was the practice in Cornwall, and were refused. They then attempted to fix the cost of the bargains for various pitches let to tribute pares (groups of miners) at prices which suited them. Several were dismissed for organising a ‘combination,’ and the names of those who had agreed not to bid for each other’s pitches on setting day were thrown off the mines. Their names were circulated in the vicinity so they would be unable to secure work elsewhere. An agent, who had been bribed and who was in collusion with the bargain takers, was also sacked. There is less evidence that the Cornish were employed in any significant numbers on the rival Irish-run mines of West Avoca.

That there was a divide between the English and Irish companies became even more apparent in 1798 when the Camac Brothers and John Howard Kyan who owned the mines at West Avoca were leaders in the Irish Rebellion, while the East Avoca Mine Captains were strictly loyal to the Crown. The Wicklow mines were a perfect training ground for the United Irishmen (UI) Rebels who came from all over posing as miners. They joined the mine militia, received arms and training, and then returned to their own UI cells.

M.P. Sir John Parnell, described the mine militia as a most dangerous body of men to the peace of the country. In fact, the mine militia were found to be so infiltrated by the UI that they were actually disbanded by the government as the rebellion began. The Hibernian Mining Company was poorly managed, expending money on useless surface works and a smelter at Arklow, and utilised primitive methods of pumping and drainage. The West Avoca mines were abandoned before 1800, while the East Avoca mines creaked on through the years of economic uncertainty in the copper market, followed by the post-Napoleonic depression.

Getting There

Cornish fishermen made frequent visits to Howth, Skerries and Arklow where they traded herring caught in the Irish Sea with Irish buyers, and there was a well-defined maritime trade between Cornwall and the eastern ports of Ireland, including Arklow, Wicklow and Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). Mineral ores were exported from these ports to Liverpool or Swansea. The Cornish-operated mining company (see below) maintained an ore yard on Wicklow’s South Quay as did the Connaree company. The ores of West Avoca were exported from Arklow. Passages could be readily obtained aboard vessels plying the Irish sea from Cornwall, Liverpool or Swansea.

The ‘Sulphur-pyrite’ Boom Years: Hodgson in West Avoca

The nineteenth century fortunes of the West Avoca mines were largely dominated by businessman, Henry Hodgson, a native of Workington, Cumberland. He took over the abandoned Hibernian Company’s workings in 1822 and mined Ballymurtagh and Ballygahan. In order to work Ballymurtagh thoroughly, Hodgson was obliged to bring in capital, and he set up the Wicklow Copper Mining Company in 1827. This enterprise was managed by his nephew, Edward Barnes, while Hodgson maintained direct control of the Ballygahan Mine.

Up until 1839, most of the sulphur used in the production of sulphuric acid was produced in Scilly, Italy. Due to this near monopoly, the King of Naples increased the price of sulphur from £6-10-0 a ton in 1836 to about £14 a ton in 1839. A rapidly industrialising Britain was importing around 45,000 tons in 1838.

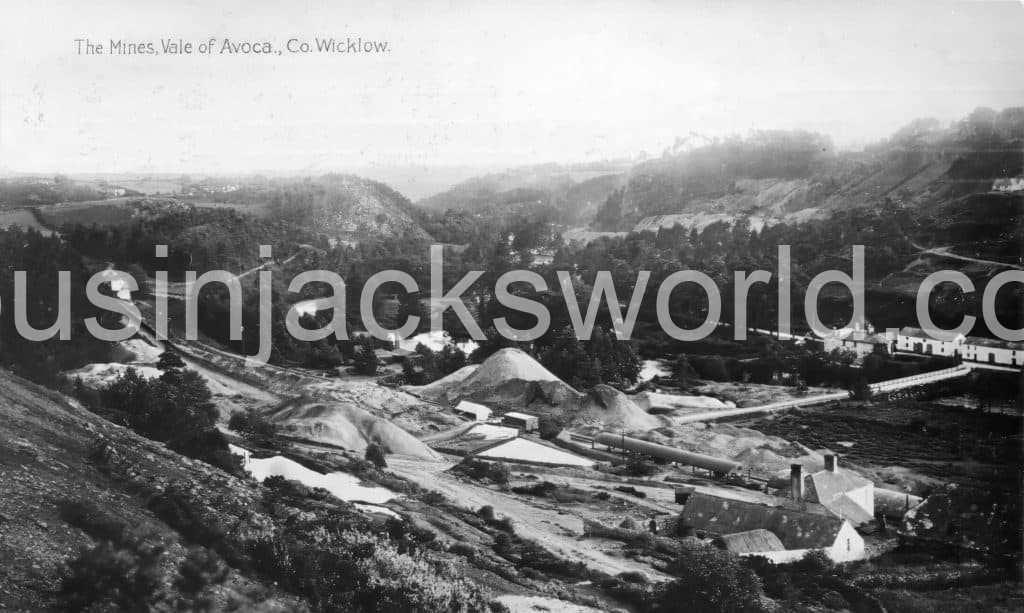

This drastic increase in price spearheaded the need to source alternative sources of sulphur. Avoca had a locational advantage, in that it contained the only commercial deposits of bisulphuret of iron in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Hodgson and the other mine operators seized a golden opportunity to supply the British market and the low-grade sulphur pyrites of Avoca, previously thrown away as attle suddenly became very valuable. It was reported that the mine roadways were even dug up to extract the sulphur. The first cargo of sulphur pyrites was dispatched from Ballymurtagh in December 1839, and annual production ran at around 20,000 tons thereafter. Unlike mining in East Avoca which was exclusively underground, a large iron sulphide (pyrite) lode was mined at the North Lode open pit in the 1850s. This open pit was, for a time, reputedly the largest open pit in the world.

These were the boom years of the Avoca mines, which made a fortune, as captured by the Tipperary Vindicator in September 1844:

“It is highly gratifying that the favourable position in which the mines of the Avoca Valley were placed by the force of the sulphur monopoly in Naples has been sustained up to the present day the judicious enterprise of the proprietors and the steady improvement of the produce. Mr. Roper states the number persons employed in this district to be about 2,000, and that from 500 to 1,000 carts are daily employed in bringing the ore to Wicklow and to Arklow for exportation.”

Indeed, the provision of horses for transporting ore was a constant problem, as the British army were constantly commandeering mine horses, so Hodgson developed a mineral tramway using horse drawn wagons to Arklow. The original dry stone mineral tramway arch still exists to this day at West Avoca and is the only original one of its kind in Ireland. The Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford Railway Act of 1859 authorised the Dublin and Wicklow Railway to extend their line to Gorey via Avoca and to buy up the tramway and stock for £30,000. The mainline railway could be laid along the route of the tramway and in 1861 the railway company took over the tramway. For a period, the tramway from Avoca to Ballyraine was worked by locomotive, but from there to Arklow and the mines of Avoca, it continued to be worked by horse.

Hodgson developed the harbour in Arklow through a poor law famine relief scheme and maintained control of the port until the local government act of 1872. He never allowed his competitors in East Avoca to use the port. Their ores were shipped from Wicklow or Kingstown.

When the sulphur market declined due to the opening of vast reserves of pyrite at the São Domingos Mine in south west Portugal, Hodgson decided to develop his own chemical works at Arklow to process raw sulphur from his mines. He could not obtain a site from the local landlords but found some ground at Arklow subject to flooding which belonged directly to the crown and applied for, and was granted a lease for it. His factory was the forerunner of Kynocks and Irish Fertiliser Industries, and gave Arklow its legacy of chemical plants. The Templerainey area of Arklow in particular resembles an English town in design, and was constructed to accommodate the specialist technical staff Hodgson brought across from England to run his chemical plant.

The chill wind of competition from the mines such as São Domingos, Rio Tinto and Tharsis in the Iberian pyrite belt, and the innovations made by those companies in sulphide ore processing and chemical production, delivered a body blow to the West Avoca Mines. Ballymoneen closed in 1861, Ballygahan Mine in 1879 and the Wicklow Copper Mining Company was wound up in 1886.

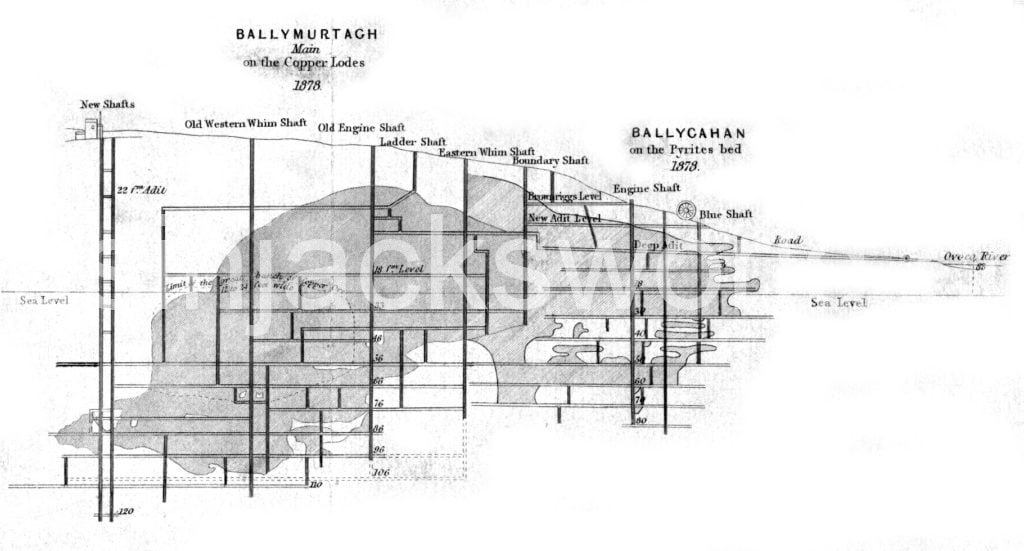

One of the most visible signs of industrialisation during this period was the erection of steam engines for pumping, crushing and winding, that replaced horse whims, waterwheels and water pressure engines from the mid-1830s onwards. With the exception of Ballygahan, which was worked by waterwheel, the West Avoca mines deployed steam engines and the majority of these were manufactured in Cornwall. Ballymoneen installed a 22.5 double acting rotary engine for pumping and winding prior to 1861. Ballymurtagh alone installed nine engines, including a 50-inch manufactured by Harvey’s of Hayle, and two winding engines, a 20-inch on Old Eastern Whim (1836) and a 30-inch on Forge Shaft (1860), both also manufactured by Harvey’s of Hayle.

The ‘Sulphur-pyrite’ Boom Years: Messrs Williams in East Avoca

Mining Engineer, Richard Griffith, visiting mines throughout Ireland in 1829, stated that one of the Copper Mines of Avoca had already been wrought to the depth of 100 fathoms, which he stated, ‘must stagger the opinion of some learned Cornishmen, who ventured to predict that all the Irish Mines would fail in depth’ (Dublin Evening Post, March 1829).

Far from believing the mines would fail at depth, the potential of the Avoca copper mines had caught the attention of people in Cornwall, including Thomas Petherick of Penpillack near Lostwithiel, who conducted a series of experiments on the electro-magnetism of metalliferous veins at the nearby Cornish-managed Connoree copper mine, which were noted to have been the first of their kind in Ireland. The Connoree Company had already installed a 30-inch engine for pumping in the early 1830s, and a further three would be erected on this mine; two for winding and one for pumping, before the mine closed in 1875.

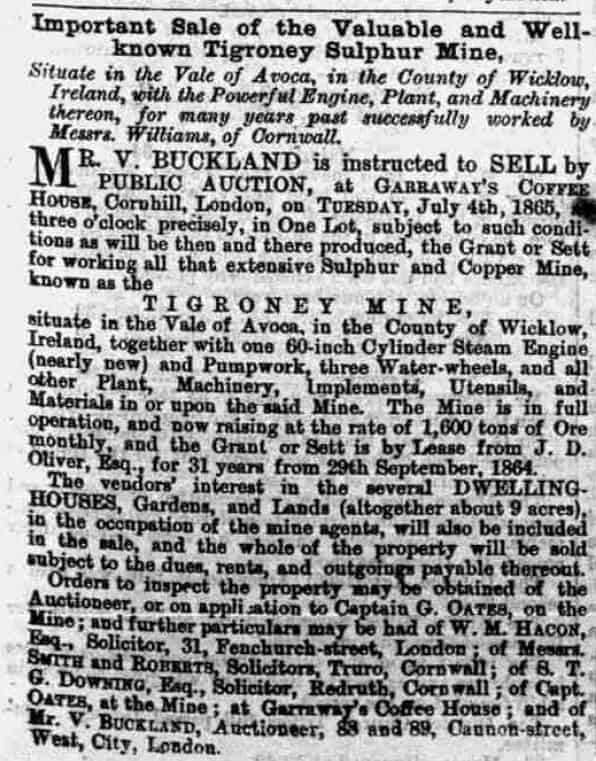

But most significantly, mining magnates, the Williams of Scorrier, who acquired mining ventures outside Cornwall including in Wales, Gongo Soco in Brazil, and El Cobre Cuba, decided to enter the Irish mining market. In 1833 they acquired a 31-year lease of the Cronebane and Tigroney Mines from the Associated Irish Mining Company (AIMC), after the previous proprietor, Richard Johnson, had failed to work them adequately. The purchase of the lease for the sum of £14,000 was a milestone in the history of Avoca mining. In June 1861, the Wicklow News-Letter stated:

“… bad management and ignorance of the first principles of mining by the native agents made it a ruinous affair to its former proprietor; but the introduction of Cornish skill, and the more advanced modes of working mines soon altered the scene—large returns immediately followed the change of proprietary, and the first year’s operations very nearly repaid the purchase money. Since this continuous success has followed, and we shall not be accused of exaggeration if may say that between £100,000 and £200,000 have been realized from the property. The present raising exceeds 40,000 tons annually, and profits £20,000 to £30,000; this has been one of the sources that has added to the immense wealth of the Williams’ family, whose world-wide fame as miners, merchants, bankers, and landed proprietors needs no comment.”

The purchase of the leasehold proved to be highly fortuitous, as the Williams’s benefitted from the sulphur-pyrite boom years. They immediately brought in skilled Cornish mineworkers, engineers and managers to rehabilitate the mines. During their management, the Williams’s adopted scientific methods of mining, including having the mineral property thoroughly surveyed and reported on by Captain Charles Thomas senior of Dolcoath Mine, in order to plan the future of mining operations.

In 1836, a 24-inch cylinder steam engine for stamping at the Tigroney Mine, built in 1832 by Sandys, Carne and Vivian of Copperhouse Hayle, and purchased with a grant given to Johnson by the Commissioner on Public Works, was placed up for sale due to a legal case. The sale also included 48-head of stamps and other equipment, as well as the engine house, stack and boiler shed. The engine had only been in operation for two months.

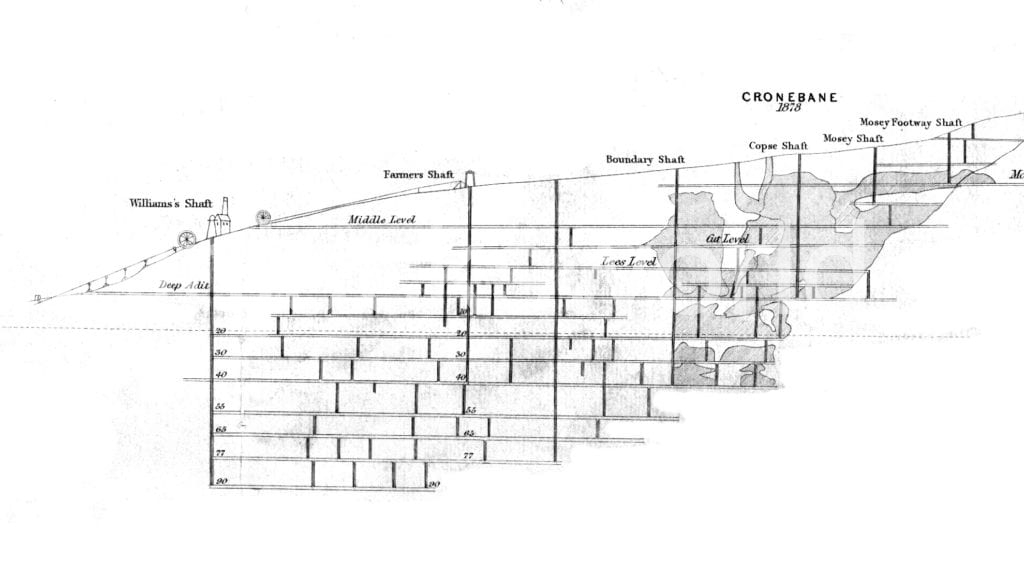

The Williams’s introduced improved methods of working and installed three new steam engines. Two of these were winding engines: a 24-inch at Boundary Shaft, installed sometime before 1853, and a 40-inch at Baronet’s Shaft, erected in about 1860. The latter engine (and very possibly the former) was manufactured at the Perran Foundry in Cornwall, an enterprise in which the Williams held an interest. The other was a 60-inch cylinder pumping engine, installed at Tigroney’s aptly named Williams’s Shaft, also manufactured at the Perran Foundry. This was the largest steam engine set to work on an Irish mine, and the pride in its installation may be glimpsed by the fact that its engine house sports an ornate brick chimney.

Prominent mining engineer, Philip Henry Argall, began his illustrious mining career on the Tigroney dressing floor as a teenager labouring ten hours a day, receiving a penny an hour in payment. At nineteen he was appointed a shift-boss in the Cronebane Mine, and two years later was promoted to the rank of assistant manager, earning him the title of Captain. In December 1875 he was considered sufficiently experienced to be appointed Agent in charge of the Cronebane Mine. His careful and novel experimentation with cementation in launders underground saw the world’s first monorail installed inside a metalliferous mine. His remarkable career as pioneer in cyanidation is described here.

Argall’s experimentation was impacted by a feud that erupted between John Michael Williams (1813-1880) and his uncles and cousins. This resulted in a legal case in 1862, after which their intertwined business interests were re-divided to enable the grandsons of old John Williams (1753-1841) to go their respective ways. In 1865 the Tigroney Mine was placed up for sale, which included the nearly new 60-inch engine. However, the Tigroney sett remained under John Michael Williams’s control and was managed by Captain C.F. Williams.

In 1872 Williams and Co. relinquished Cronebane which reverted to the Associated Irish Mine Company (AIMC). Frederick Martin Williams (1830-1878) and Michael Williams (1839-1905) then obtained control of the AIMC and decided to work Cronebane themselves. In 1872 the offices of the AIMC were transferred to Perranarworthal in Cornwall. Engineer, John Hocking of Redruth, was instructed to travel to Wicklow to arrange with Captain George Oates for the erection of a 22-inch whim engine on Boundary and Copse Shafts.

Argall and his father-in-law, George Oates, remained at Cronebane, working for one half of the Williams family. Tigroney commanded the main adit (Deep Adit) into which most of Cronebane’s waters drained from Mosey Adit (later known as Cronebane Deep Adit) down Copse Shaft and into the Tigroney sett. Argall knew from repeated analyses of the mine waters that Cronebane Mine was furnishing its principal copper content, which did not matter when the two setts were being worked by the same company. But times had changed and after convincing Captain Oates, Cronebane’s Agent, of this fact, a demand was made on the Tigroney company for a share of the profit from Tigroney’s precipitation plant. This was ‘turned down hard’ by Cornish Agent, Samuel Uren, and Captain Williams. Arguably, it was the feud in the Williams’s family which drove the novel nature of Argall’s underground cementation process.

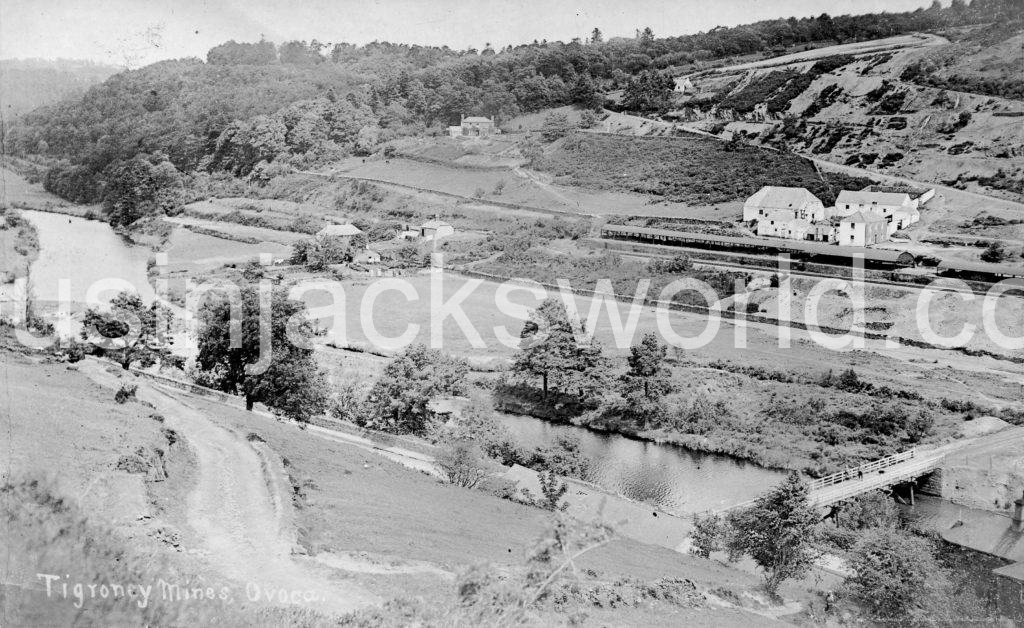

On John Michel Williams’s death in 1880, a meeting of the AIMC resolved to offer the company’s freehold land and machinery for sale. Tigroney was sold, and the 60-inch engine was purchased by Harvey’s of Hayle and Loam. They moved it from the mine in 1881. In April 1882, Captain Higgins advertised a 30-inch engine and a 12 ton Cornish boiler for sale at Tigroney Mines. By 1882, it appears all the steam engines had been removed from the East Avoca mines, for the Bray and South Dublin Herald notes that Cronebane’s ores were being lifted by horse whim. The machinery for pumping the water from the mine was driven by an undershot water-wheel of upwards of 20 horse power.

In 1881 the company sold their interest in the Cronebane Mine for the sum of £2,000 to Mr Thomas Rivington, and in 1882 the dissolution of the AIMC was undertaken and the company was legally dissolved by 1884. In 1896 the Cronebane and Tigroney Mine was being operated by the Cronebane and Tigroney Mining Co. of Dublin, with James Higgins as Mine Captain, employing 29 underground and 11 surface workers.

The Cornish Community

Although there was never a discrete Cornish community as in settlements such as Moonta, Real del Monte or Morro Velho for example, by 1861 scarcely a local mine had not been under Cornish management. Examples include Captain Silas Evans, formerly Agent at the Newtownards Mine who captained Ballymoneen. In the 1840s, Captain Henry Thomas F.R.S and Captain Stephen Roberts, were at the Connoree (Connary) Mine. Stephens went to the Bruce Mines in Canada but returned to Connoree. He died on 17 April 1853 aged 66 after a long illness. This mine was later captained by George W. Maynard. There were a succession of captains at the Tigroney and Cronebane mines, including James Higgins who originally arrived as a purser, and Captains Argall senior and junior, Darlington, Goldsworthy, Hodge, Oates, Reed, Thomas, Uren, and Williams.

Another captain was William Lean, an Agent at Cronebane and resident at Ovoca Cottage who was formerly of Carharrack. He and his wife Elizabeth Tuckfield moved to Avoca in about 1841 where three children were born and baptised in the Rathdrum and Castlemacadam parishes by Wesleyan ministers. Lean sent his sons Francis and John Henry, home to be educated at the Trevarth House Grammar School in Gwennap in the late 1840s and 1850s. Captain Lean died on Saturday 23 August 1856 in a mining accident in the Cronebane Mine at 6.45am. He is buried at the Castlemacadam churchyard.

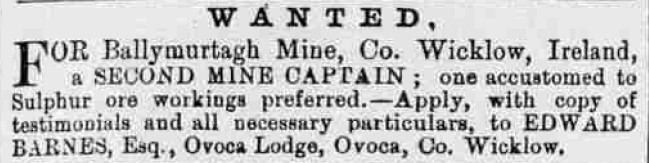

The Cornish presence was not as prominent in West Avoca, where men from Cumberland predominated. In 1871, an advertisement was placed in the West Briton for a second mine agent for the Ballymurtagh Mine, and in January 1886, Thomas Uren of Chacewater died aged 71 at the Ballygahan Mine from heart disease.

The Cornish were a relatively closed community, bound by a shared religion (predominantly Methodist) marriage and kinship ties. Thus, we find Captain Samuel Goldsworthy of the Cronebane Mine marrying Jane, the second daughter of Captain Stephen Roberts of Camborne and the former manager of the Connoree Mine, at St Andrew’s Church of Ireland in Dublin in December 1844. His wife Hannah was a Goldsworthy, so there was undoubtedly a family connection. Captain Robert’s eldest son Stephen worked at the mines as did his son William, who took over at Connoree after his death. Philip Henry Argall, whose family were related to Silas Evans, the manager at Ballymoneen, married Frances Ellen Oates, the daughter of Captain George Oates of Cronebane, who had been born in Kenwyn Parish.

The Cornish were dispersed among the various mines and mainly resided on the mineral setts in dwellinghouses surrounded by gardens that were owned by the various companies, including of course, the count houses. At Connoree Mine, the agent and head engineer resided in houses provided by the company, which also owned the lease on nine cottages built to house its workers.

By contrast, around one third of the Irish mineworkers lived in crude one-roomed botháns (cabins) on the roadsides, or on wasteland close to, or on, the mineral setts. Around eleven percent of these housed more than one family. There were once 274 such dwellings clustered on the Tigroney-Connary Hill in East Avoca and a further 63 on the opposite side of the valley in West Avoca. At the townland of Ballymurtagh, in 1833 the smallest house was let at 12d a week, equivalent to a day’s work for a labourer. However, many miners preferred to reside in a bothán than pay the rent on a better class cottage built by the mining company. With over two thousand people employed at the mines towards the mid-nineteenth century, housing was at a premium and conditions were grim for many. A French visitor to the mines in 1836-7 wrote:

“Along the Avoca Valley I saw cottages so miserable they are impossible to describe. Most of them have neither the size nor the type of organisation that one would find in sheds to house animals. They are propped up against the ditches which line the road and are, without a doubt, the most unfortunate of structures, scarcely having a wall that merits the name, without chimneys or windows and none without a small heap of straw and farm dung – the traveller would never suppose that these are human habitations.”

Today, there is little evidence that the cabins that sheltered the hundreds of Avoca mineworkers ever existed, as the majority of these dwellings were constructed of cob and thatch, and have long since melted back into the landscape.

Conditions underground were poor. Captain Argall recalled that huge falls of ground on the great pyritic lode in Tigroney and Cronebane were common and the temperature in the stopes of both setts was intense, seldom below 100 degrees F., and in some cases attained 140 degrees F. The water drops that fell from the roof of the stopes ‘were simply saturated solutions of sulphate’, and he recounted how this acid water caused nasty sores on the backs and arms of the semi-naked miners, adding that one man lost the sight of his right eye by the corrosive action of a single water drop. The bad air was also noted to have caused bronchitis.

In common with many other mining regions, there were numerous incidents of fighting and rioting, the cause of which was amusingly described by the Wicklow News-Letter in 1864: ‘…they all knew the character of the Irishman when under the influence of a little drop who “comes out, meets a friend, and for love knocks him down.”’ Sometimes this culture of heavy drinking due to the presence of numerous beer shops and shebeens, led to grievous bodily harm and the occasional murder. But the Cornish, many of whom were teetotal, seem not to have been molested by the Irish miners of either Catholic or Protestant persuasion, and the communities lived peaceably enough together.

This was undoubtedly because the Cornish were viewed as having brought a degree of prosperity to the valley, as noted in the Waterford Chronicle in February 1834:

“Edward Legh, of Lewesham House, Kent, Esq., chairman of the associated Irish mine company, accompanied by his co proprietors, Captain Jefferies, of the Navy, and Charles Hoghton, Esq., of the Regent’s Park, arrived at Gresham’s hotel on Tuesday, with the view of extending the works at their very valuable mining district at Cronebane, County Wicklow. We understand that the chairman has recently granted a lease of the royalties of Cronebane to that highly respectable and enterprising firm, Messrs. Williams and Brothers, of Truro, Cornwall, bankers. These gentlemen having truly the interest of Ireland at heart, have strongly evinced (contrary to the general custom adopted in this country) their beneficent views towards the welfare of the surrounding neighbourhood, by making most liberal weekly payments, which system is duly appreciated by a most grateful and industrious peasantry.”

Besides giving decent wages, the mine proprietors ensured that their workforce and their families were shielded from the worse effects of An Gorta Mor (the famine) of the late-1840s. Therefore, it was not as acutely felt in the Avoca mining district as it was in the mining districts of West Cork for example. A memorial at St Saviours, Arklow, to Henry Hodgson and his wife, includes the words: ‘… and with special remembrance for their help and work during the Irish famine of 1847.’

Later in the century, it became harder to source local labour for the mines, as many men had gone over to the Cumberland iron mines seeking work. In 1872, Captain Oates grumbled that he had been left with sluggish beings – the castaways from other mines, but he intended ‘to knock them to their senses.’

Cornishmen such as Captain James Higgins of Scorrier, noted by the West Briton in October 1886 to be, ‘the right man in the right place,’ was very well-respected. In the autumn of 1886, he arranged for 150 men and boys employed at the Tigroney and Cronebane mines to have a day out at the Seven Churches at Glendalough in the Wicklow mountains. This novel event, undoubtedly modelled on the much-loved Cornish tea treat of home, saw the employees enjoy a splendid luncheon followed an afternoon of cricketing and boating on the lake, accompanied by music and song. The day was brought to a close with tea and cake served on the green by Captain Higgins’s wife, Sarah Jane Luke, who had been born at the Morro Velho Mine in Brazil.

In July 1898, the Wicklow News-Letter reported that Captain Higgins’s mineworkers proved worthy competitors to the tenantry of Mr Wynne, who had laid on a variety of sports at the cricket ground at Tigroney, including cricket and a tug of war in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. This was followed by refreshments, and tea and cake at the pleasure grounds, after which the crowd engaged in spirited dancing. Proceedings were rounded off by a speech given by Captain Higgins and a hearty rendition of God Save the Queen. Higgins was undoubtedly the longest serving Cornishman at the Avoca Mines. At his death in 1920, he had spent 54 years in the employ of various companies at Tigroney and Cronebane.

Several published sources state that a small Wesleyan chapel had been built in the townland at Knockanode near the village of Avoca for the benefit of the English residing in the valley in 1840. However, it appears that the actual date of construction was much nearer to 1858. The ground was given by William Joseph Levinstone. Another Wesleyan Chapel had been built at Abbeylane in Arklow, where permission to perform marriages was granted in 1858. The Avoca chapel is set back from the road in its own grounds. It is a small, single storey building constructed over a basement (since sealed and disused), and is of plain classical style with round-headed Georgian style windows.

The Tigroney Mine adventurers and Messrs Williams subscribed to the fund to aid in its construction. In July of 1858, the Wicklow News-Letter advertised that two services were to be held in the chapel by Wesleyan minister, the Rev. Daniel McLefee. Tickets to attend his sermons cost one shilling and were obtainable from several Cornish residents of the area, including Captains Reed, Thomas, Hodge and Darlington, and Mr Williams of Ovoca. The trustees hoped that their numerous friends who had assisted in the erection of the chapel would continue to support their original purpose ‘not to rest until the building be free of debt,’ by purchasing tickets. The collections at the end of each service were to help achieve this aim.

In 1864, the Wicklow News-Letter noted how a Sabbath service was held every week ‘for the benefit of the English mining population in the Vale of Ovoca.’ It was at this chapel that two of Captain George Oates’s daughters were married: Ellen Frances, to Philip Henry Argall on 31 August 1876, and Martha, his eldest daughter, to John Tippett of St Agnes, in February 1878.

When the Cornish drifted away from Avoca as the mines declined from the 1870s, the chapel lost a good deal of its support. In 1902 it was noted that the congregation was much diminished from thirty or forty years ago, when several thousand miners found employment in the area, and Methodism was numerically strong. There were still two weekly services, but throughout the twentieth century the congregation dwindled. In 2019, permission was granted to turn the chapel into a three-bedroomed private residence.

An Anglican church was built at Castlemacdam in 1819 for the Church of Ireland community and was consecrated in 1821. This was superseded by the need for a larger church, opened in 1870 on two acres of land given by Lord Powerscourt, and a quarry of stone to construct it was offered by the Earl of Meath. Generous subscriptions were received from the miners of Ballymurtagh, its owner Henry Hodgson and his manager nephew, Edward Barnes. Messrs Williams of the Tigroney and Cronebane Mines, Sandys Vivian and Co., engine makers of Copperhouse, Hayle, which had supplied equipment to the Avoca mining companies, and Bickford Smiths of Tuckingmill, who sold their safety fuse to the local mines, were among the subscribers. The former church is now a gaunt ruin, but the old churchyard contains several Cornish memorials, including that of William Lean of Carharrack and John Paul Moyle, a native of Mingoose, St Agnes, who died aged 24 in 1841.

In August of 1859, the foundation stone of a new Anglican Chapel of Ease to Castlemacadam was laid at Connoree Mine close to the Count House, to serve the parishioners who resided some four or five miles from the church at Castlemacadam. The chapel named Saint Bartholomew’s capable of holding 120 persons, opened for divine service in September of 1861. The ground was given by Joseph Selkeld Esq. and the building cost £355, raised mainly by subscription among those connected with the mines, and a generous donation of £50 from Selkeld. It is not clear what support the Cornish gave this place of worship, as most would have been of Methodist persuasion. In May 1861, several leading Cornishmen did attend a presentation by the Protestant parishioners of Castlemacadam to the Rev. W.H. Brassington, including Stephen Roberts, Richard Thomas, John Hodge, Silas Evans, and John Michael Williams.

Twentieth Century Mining

Some of the mines, including Tigroney, East Cronebane and Ballymurtagh, were in small operation in 1919, but apart from some exploration, the area was largely abandoned until 1958. After that year, there were two periods of larger-scale mining. The first, by St. Patrick’s Copper Mines lasted from 1958 to 1962. A new decline was driven into West Avoca and a new level into East Avoca, both from the river valley. Mining was by open-stoping, sometimes with caving which extended to surface, and 3.1 million tonnes of ore grading 0.74 percent copper together with 120,000 tonnes of pyrite were extracted. The operation was not financially successful and the company went into receivership.

The mine was re-opened in 1969 by Avoca Mines Ltd. In addition to continuing underground extraction in West Avoca, using open stoping with backfilling, three open-pits were worked: Pond Lode Pit (West Avoca) from which one million tonnes of ore were extracted; East Avoca Pit from which 900,000 tonnes were extracted; and Cronebane Pit (East Avoca) mined for 500,000 tonnes. A total of 8.9 million tonnes of ore grading 0.73 percent copper, plus 540,000 tonnes of pyrite was mined before closure in 1982. Fittingly, the last Mine Manager was a Cornishman, Alan Thomas from Camborne.

Industrial Legacy

Unfortunately, many of the mining features of the nineteenth century have been destroyed by twentieth century open casting, including the miles of underground workings. At East Avoca, the remains of two engine houses – the whim engine house at Baronet’s Shaft and the splendid pumping engine house at Williams’ Shaft – are extant, the former in rather poor shape. At Connoree, the only visible remains are an engine house stack.

On the Ballymurtagh site are the remains of the fine drawing engine house at Twin Shafts and the engine house and its accompanying stack at Forge Shaft. Other remains include a tramway bridge at Ballymurtagh.

Sadly, despite considerable opposition at local and national level, the state, which owns the site, has further degraded this important mining landscape by undertaking intrusive remediation works, particularly in East Avoca. This work included sealing the various adits, and the landscaping and removal of spoil heaps, in order to ameliorate acid mine run off into the Avoca River. Unfortunately, this has divorced the discrete industrial features from their landscape context, while no funding (apart from that raised by independent heritage groups) has been forthcoming to conserve the extant remains of the Cornish engine houses. Read more about this here

Further Reading on the Avoca Mines

Cowman D (1994) ‘The Mining Community at Avoca 1780-1880’ in Wicklow History and Society, Dublin, pp. 761-768.

Wicklow County Council (ed. Martin Critchley) (2008) Exploring the Mining Heritage of County Wicklow. Download it here

Rev. P. Dempsey (1913) Avoca, a History of the Vale

Visit Avoca

The Avoca Courthouse Heritage Centre contains information on the mines. Beyond the public roads and pathways, access over the mine site is strictly controlled by the state.

Watch some aerial footage captured by 4k drone in 2016 of the Avoca mines prior to remediation works:

The Mining Landscapes of County Wicklow

© Sharron P. Schwartz