El Cobre, Cuba

All content is copyright © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2022, and may not be reproduced without permission

El Cobre: Cornwall’s Caribbean Charnel House

El Cobre (Spanish, ‘The Copper’) is about 19 km north west of Santiago Bay in the Sierra Maestra Mountains of south eastern Cuba. It was the site of the first copper mine to be worked by the Spanish in the New World. Operations began on a highly visible gossan outcrop in about 1544. For over three centuries its Spanish owners mined the deposit using mainly press-ganged indigenous people and imported African slaves.

In the late seventeenth century, the mine was abandoned by its Spanish owner who was too heavily indebted to his government to work it. It remained idle until a revival of interest in Cuban copper mining occurred as a result of the 1825 overhaul of the country’s mining regulations. This permitted non-naturalised foreigners to denounce, register and form companies to work mines.

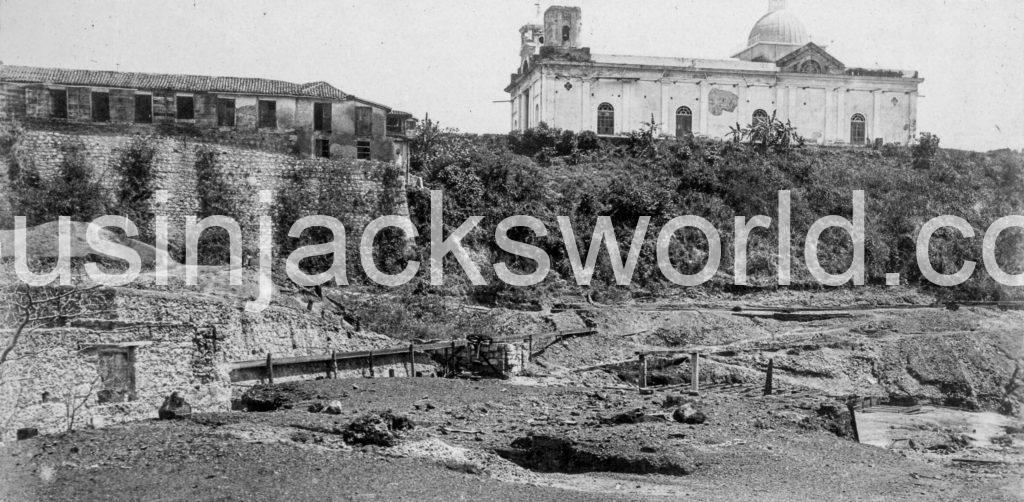

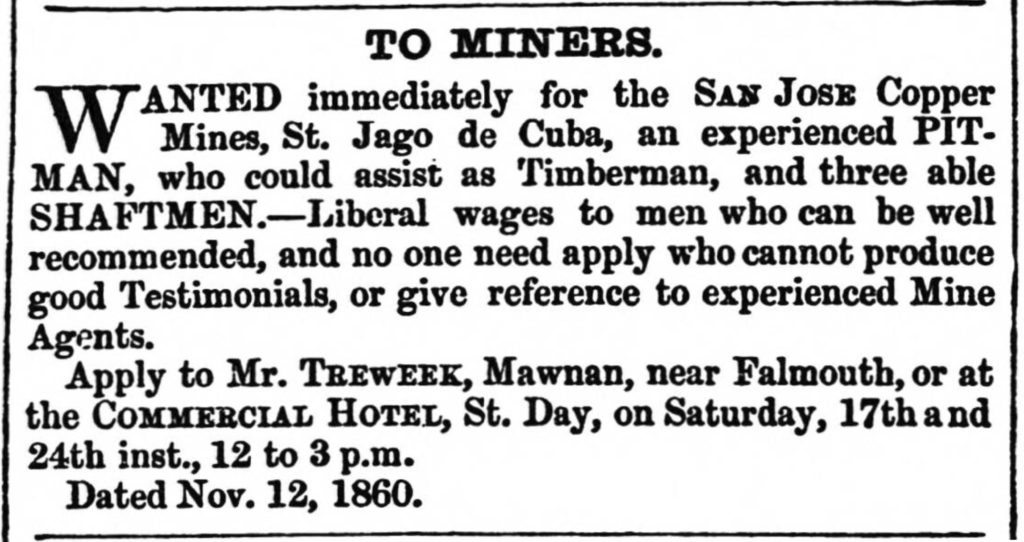

A company named the San José, set up in 1825 by two Cubans, was the first to exploit a mine located on the south face of the hill below the Basílica housing the famous Marian statue known as Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre, Cuba’s most important shrine and a centre of pilgrimage. A Peruvian miner was the first foreigner to register a copper mine in 1827.

Two years later a gentleman from Santiago de Cuba was attempting to recover a mortgage debt on a neighbouring property, and out of curiosity assayed some waste from one of the mines. It proved to be remarkably rich, leading him to denounce a mine in the vicinity of ‘Villa del Cobre’. The next year a Havana-based Spanish gentleman registered three more mine setts there.

British Capital and Cornish Skill

However, to fully exploit the copper deposits of El Cobre by deep lode mining methods, required large amounts of capital which was near impossible to raise in Cuba. Britain, which was capital-rich and had spearheaded the revival of mining in South and Central America, was the obvious place to seek large-scale funding.

The British Consul, John Hardy, and his son John junior, joined forces with the man who had discovered the ore deposit and a prominent Santiago merchant. After taking advice from a skilled Cornish mining captain, they acquired several additional mine setts at El Cobre. In 1830 they formed El Compañía Consolidada de Minas del Cobre and admitted the Havana-based gentleman to the company, believing he would prove useful in navigating colonial mining laws. Hardy then used his London contacts to create a limited company (the Royal Copper Mines of Cobre, also known as the Cobre Mining Company) with a capital of £480,000 in 12,000 shares of £40 each. Five thousand five hundred shares were automatically transferred to the partners.

One of the partners then sold his stake to set up a rival company called the Cubana Cobrera. This commenced operations in 1836 on a sett contiguous to one belonging to the Cobre Mining Company. A further British venture, El Real de Santiago (the Royal Santiago Mining Company) was announced in 1836. This was capitalised on the London stock market by the sale of shares after an initial outlay of some £35,000. This had been raised by the proprietors to send out experienced Cornish mineworkers, to develop infrastructure, and to purchase supplies. Among the Directors was Michael Williams of Scorrier House near Redruth, Cornwall. Indeed, one of the company’s mines was named Trevince after one of his Cornish estates.

Although some Welsh and Irish mineworkers were recruited, both of the British companies looked to Cornwall, the foremost mining region in Britain, to supply the bulk of their technological and labour needs. From 1836 to the end of 1839, at least 136 Cornishmen migrated as employees of the Cobre Mining Company alone. Many hundreds of Cornishmen worked at the El Cobre Mines from the mid-1830s until the decade-long insurrection against the Spanish government broke out in 1868.

Getting There

Their journeys began at the Cornish ports of Portreath and Hayle where they embarked vessels transporting Cornish copper ore bound for the smelters of Swansea, south Wales. Very occasionally men left from Falmouth on a Packet mail ship bound for the West Indies. From Swansea they journeyed across the Atlantic aboard a copper ore barque to Santiago de Cuba. A typical Transatlantic passage took around 6 weeks.

Once they had cleared customs at Santiago, the recruits travelled to the mines on horseback, a journey that took about 2 hours. In 1843, a 21km mule-driven railway was built to link the mines to the coast. Its terminus was at Punta de Sal which lay a boat ride away across the harbour. This railway was later converted to steam.

The El Cobre Mines

The El Cobre mines lay on a ridge that traversed the head of a picturesque valley that wound its way up from Santiago de Cuba. By the 1840s four main companies were mining there, two of which were solely British.

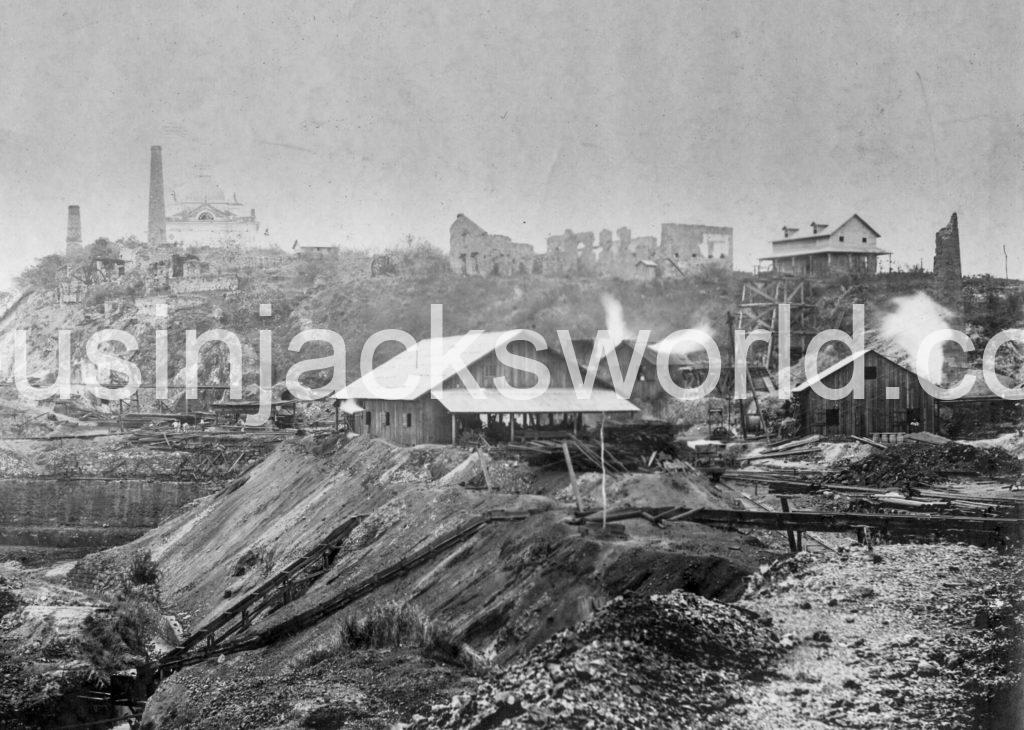

As the Cuban government placed no import duty on Welsh coal or British-made machinery, many tonnes of heavy mining equipment including steam engines, Cornish rolls, stamp batteries, calciners, waterwheels, whims, rising main, kibbles, iron rails, wagons and tools were imported. A significant amount of the specialist machinery was cast at the great Cornish foundries of Perran, Harvey’s of Hayle, and Sandys, Carne and Vivian. Other Cornish companies supplied sieves, safety fuse, ropes, chains, surveying equipment and even mineworkers’ clothing and hats.

The mines of the four companies were concentrated in a relatively small area, and all made use of similar machinery. The large number of engine houses and stacks, whims, extensive dressing floors and huge heaps of colourful mine waste, created a landscape that was remarkably similar to the heavily mined areas of Gwennap in Cornwall.

The Casa Grande (Mine Office) of the Cobre Mining Company, the biggest and most successful mining company, was sited atop a rocky prominence, with the Basílica at the opposite end of it. Both buildings overlooked a chasm containing the mine workings.

Some of the shafts at the El Cobre mines attained depths of over 400 metres. Because it was a sulphide ore body, it was not unusual for temperatures to exceed 30 degrees centigrade in places, and the water seeping out of the rock faces was acidic and warm. Mineworkers therefore worked half naked. The Cobre Mining Company had installed a two-tiered octagonal cage in one of their shafts to convey men to the surface. Although it did not reach the very bottom levels, this meant that heat-exhausted men coming off shift did not have to climb hundreds of metres of ladderways.

This company also provided a miners’ dry in a long wooden building furnished with bath tubs. Miners coming off shift were instantly immersed in a warm bath where they were washed and massaged by female black slaves which helped them to become accustomed to the abrupt change in temperature. However, the Resident Director, John Hardy junior, had a reputation for ruthlessness when it came to caring for men who fell ill, often refusing to repatriate those who were unable to work and were probably unlikely to fully recover.

The workings were characterised by enormous stopes where the rich ore had been mined out. These were shored up with a forest of timber by skilled Cornish timbermen to prevent collapse. The timberwork in one such stope resembled the vaulted ceiling of a cathedral. The cupreous waters pumped from the mine were conducted into wooden launders full of scrap iron where metallic copper was precipitated. The richest ore needed little treatment besides hand dressing, but the poorer ores were calcined, stamped and jigged before being exported to Swansea for smelting. After the Cuban government insisted that copper raised in Cuba was smelted there, the Cobre Company built a smelting works at the eastern end of the mines.

One of the more unusual sights at the El Cobre mines were the large number of camels. These were imported from Africa and were used alongside mules to haul the copper ore to the coast for shipment to Swansea before the railway was built.

The Mining Community at El Cobre

The town of Cobre was on a reverse slope to the west of the ridge, and on the south rose a range of mountains from Hardy’s Top to Monte Real, 295 and 591 metres respectively above the mines. The former sugar loaf-shaped mountain was named after John Hardy junior, British Consul and Resident Director of the Cobre Mining Company, who had a spacious villa built at its summit to catch the breeze. This was later used as a sanatorium by the officials of the Cobre Mining Company.

The immigrant workers lived in one-storey houses built close to the mines on the outskirts of the town. These were constructed of large posts driven into the ground at four corners and at the doorways and windows, with smaller posts driven in between. Branches were then woven around the posts and plastered on both sides with an adobe type of mortar. The exterior was painted in either blue, yellow or green and the roofs were made of semi-circular tiles. The windows had no glass, but were fitted with iron bars and wooden shutters. Nothing could be done to prevent flies and disease-carrying mosquitoes from entering.

The area was subject to earthquakes and flooding, and the climate was humid and unhealthy, with frequent outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever. Yellow fever proved particularly fatal, claiming dozens of Cornish lives each year. El Cobre earned the unenviable reputation as the Caribbean’s charnel house, and was undoubtedly one of the deadliest destinations for Cornish migrants. In 1864, about 44 per cent of ‘Englishmen’ who contracted yellow fever died at Cobre.

Those who returned to Cornwall with their health affected were known as ‘Cuba men’ due to their sallow complexions. Despite this, it was not uncommon for some men, especially among the senior management, to have their families with them at Cobre.

Life for the Cornish at Cobre was difficult, for besides the constant threat of disease, there was little in the way of familiar cultural distractions or entertainment. Some inevitably became addicted to the local rum, causing the companies to grumble about the prevalence of intemperance.

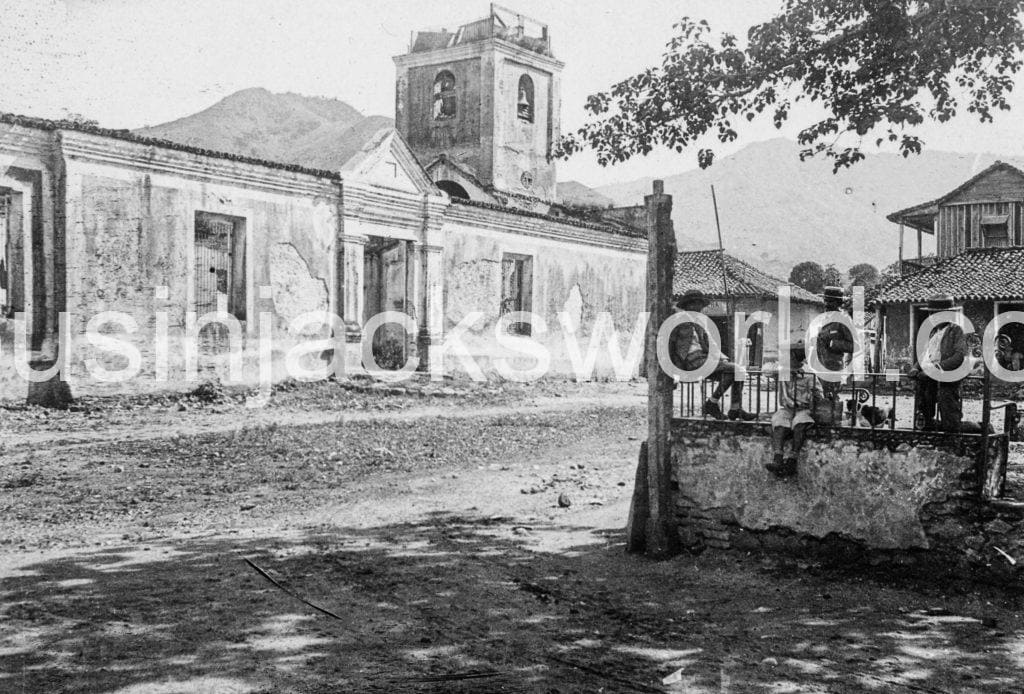

Most Cornish were disdainful of the Cuban pastimes of cock and bullfighting and their love of riotous fiestas, but more importantly there was no religious provision for them. No other religion but Catholicism was tolerated and the community was served by two Catholic churches. One of course, was the Basílica housing the famous Marian statue which had put Cobre firmly on the map as the very heart of Cuban Catholic devotion and pilgrimage. There was no way that Protestantism could be permitted to pollute this national bastion of sanctity.

But the Cornish, being mainly Wesleyan Methodists, wished to have their own prayer meetings and services and this created problems in the mid-1830s. Each Cornish recruit to the Cobre Mining Company was sent to Cuba with a Protestant Bible, which roused the suspicion of the Cuban authorities.

A diplomatic rift almost resulted in the mid-1830s when a company employee who was also a Wesleyan local preacher tried to minister to his fellow Cornishmen and was threatened with incarceration. Fearing reprisals, the company instructed their employees to show no outward signs of Protestant devotion and went to great lengths to remain on friendly terms with the local populace and authorities. They gifted a turret clock to the Basílica as a goodwill gesture in the 1860s.

As they were not permitted to be interred in a Catholic cemetery, a burial ground for Protestant inhumations was opened close to the mines. This was necessary given the unsanitary conditions and high death rate from disease at Cobre. Very few Cornish converted to Catholicism, and mixed marriages were rare. Yet the senior Cornish staff got along well with the Spanish planters living on neighbouring haciendas. They were grateful to them for their warm hospitality and invitations to hunt the wild game that abounded in the nearby woods.

For a time, the El Cobre mines were extremely well-known in the Cornish towns of Redruth and St Day and the mining villages ringing these settlements, due to the fact that the people involved in the recruitment of labour for the El Cobre mines resided in this area.

But fewer Cornish were recruited for the El Cobre mines from the late-1830s, when there were around 200 of them there. The wages on offer were not that attractive compared to those available in other, more salubrious mining fields, especially to married men who also had to maintain a family back in Cornwall. Miners received £9 per month, a blacksmith £10, and an engineman, £11. From these wages, they were expected to pay for food, laundry and accommodation. On top of that, some also paid a monthly sum into a ‘miners’ chest’, a type of insurance fund which paid out a sum of money to the mineworker or his family in times of incapacity or death.

The issue of poor wages coupled with the well-known dangers of disease, resulted in a fall in the number of Cornishmen working there. They were gradually replaced by miners from other parts of Europe, including Asturians and Isleños from the Canary Islands, who were considered to be more robust.

Numbers further declined after the Royal Santiago was wound up in 1858 following the calamitous collapse of its main engine shaft. The San José Company was acquired by the Cobre Mining Company in 1850, and even though it employed Cornish labour, this was mainly at highly skilled or senior management level. That said, during the British period, there was always a marked Cornish presence at Cobre.

The Issue of Slave Labour

As with the British-operated mines in Brazil, those in Cuba also employed slave labour. Britain abolished slavery in 1833 which had led to the emancipation of slaves in sugar plantations across the Caribbean. Yet at Cobre, mining companies registered, owned, and operated by the British were working around 700 slaves imported from Africa.

The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association with its goal of universal emancipation, campaigned for an end to this practice. But as the mining companies operated in Spanish jurisdiction where slavery was legal, there was little that could be done within the parameters of British law to prevent slave-based mining in Cuba.

Moreover, the British Mining companies were not short of support in high places, and could count several MPs, wealthy City of London businessmen and aristocrats among their Board of Directors and shareholders. So, it wasn’t hard to dilute the 1841 petition presented to Parliament by Lord Brougham, a prominent abolitionist. Although the purchase of new slaves was banned, supporters of the mining companies successfully lobbied lawmakers to strike clauses prohibiting the renting of slaves. Brougham’s Act of 1843 was rendered toothless by the British mining companies operating in Cuba, who simply switched to renting slaves from local plantation owners.

These white plantation owners brought and sold slaves at will, with no regard for keeping family members together. Cornishmen in senior management positions had the power of life and death over the company’s slaves, and were free to order beatings. Both male and female slaves were punished by being laid out or tied to a ladder and publicly flogged.

After being whipped, a further example was made of some slaves by placing them in the stocks where the lacerations on their backs oozed with blood. Runaways were punished by being chained to an enormous hardwood block which they had to pull around as they worked. But the ill-treatment of slaves at Cobre greatly distressed several Cornish eye-witnesses, particularly those who were Methodists. For back home in Cornwall, slavery had been roundly condemned in their local chapels.

Yet the stench of hypocrisy certainly hangs over the Grenfell brothers who were Cornish by descent, devout Anglicans, and shareholders and Directors of the Cobre Mining Company. Their father, Pascoe Grenfell, was a zealous supporter of William Wilberforce, and as a Cornish MP had spoken out against slavery. Yet his sons were prominently involved in a mining company that profited from slave labour. But not everyone turned a blind eye. When he learned of the company’s use of slave labour, the company’s main recruiting agent in Cornwall, a prominent Redruth Quaker, resigned his position.

Indentured Chinese

As criticism of slave labour caused unease among some shareholders, the Cobre and Royal Santiago companies decided to lessen their dependence on it by importing ‘Coolies’ – indentured Chinese labour. Their lot was not much better than the black slaves. The Cobre Mining Company accommodated them in a prison-like barracks. They were so poorly paid, they worked in virtual darkness so they could make extra money by selling the candles supplied to them by the company.

To alleviate the drudgery of their lives at the El Cobre mines, many resorted to smoking opium which was smuggled in from surrounding plantations that also employed ‘coolie’ labour. The companies did not take kindly to this as it lowered productivity, caused premature death (often by suicide), and resulted in high absenteeism. Those caught selling or smoking it were punished. On one occasion the Cobre Mining Company rounded up the Chinese and made them watch as they executed two of their countrymen who had been accused of murder. What was intended to be a salutary lesson to them did not change their attitude or behaviour.

Although they acknowledged them as hard workers, the Cornish were very wary of the Chinese, believing them to be sneaky, subversive and fanatical, unlike the black workers whom most considered to be infinitely superior men. Their poor opinion of the Chinese was merely reinforced when the Insurrection began and a group absconded from the mines and joined the rebels who were fighting the local plantation owners with whom most Cornish were on good terms.

The End of the British Era at El Cobre

The community was finally dispersed in 1869 when operations at the mine were suspended. This was the result of many factors. The ore body was said to be virtually exhausted and a local river that was the source of water for steaming the engines and for dressing ores had all but dried up. The high duty that the company had to pay to send its ore, coal and other supplies over the railway that was owned by a separate company, had long been a bone of contention. By the 1860s, the duty had become intolerable as the company’s profits were diminishing due to the declining richness of the ore. Legal proceedings were underway when the insurrection against the Spanish government began in 1868.

The company continued operations, maintaining a strict neutrality, but the fighting soon engulfed Cobre and the damage inflicted on the railway bridges dealt the decisive blow to operations. Soldiers ransacked the mines and did terrible damage to the steam engines and other machinery.

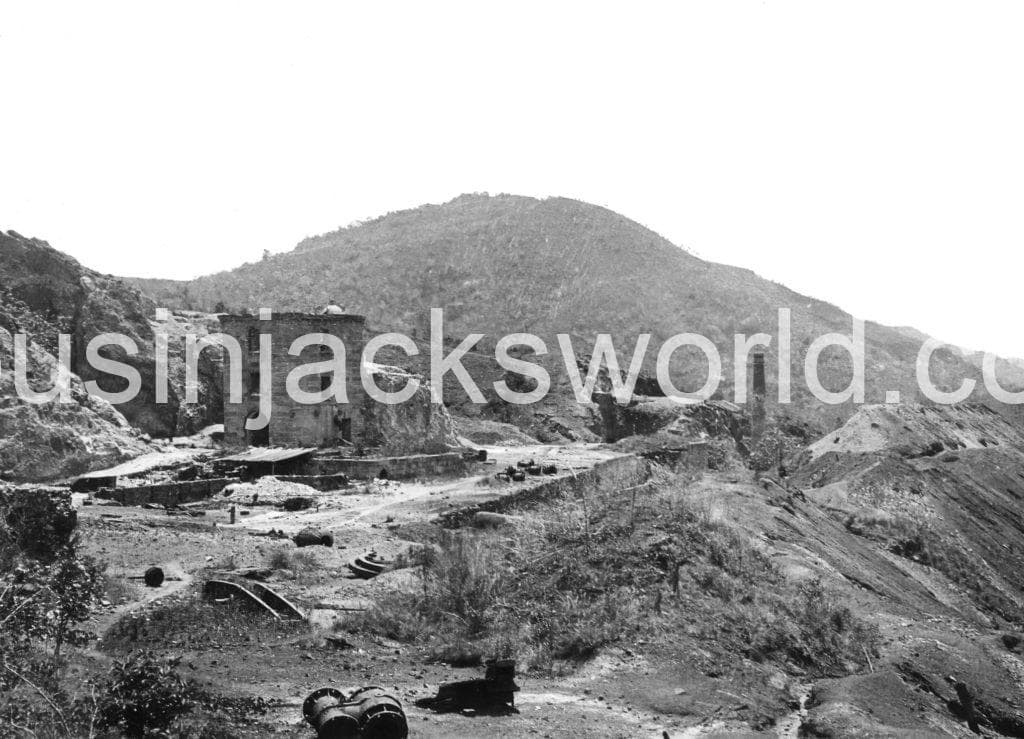

A futile attempt to re-open them was made in the 1880s, and apart from some small-scale precipitation of copper by local inhabitants, nothing significant was done at the El Cobre mines until an American company arrived in 1902. This employed some Cornish labour and made considerable progress in draining the old workings. Sadly, it was responsible for destroying virtually all of the Cornish mining features, including some rather splendid engine houses.

However, the company neglected to adequately secure the enormous stopes in the unwatered ground, and a large section of the workings collapsed, leaving the beautiful Basílica perched precariously on the edge of a chasm. This event ended Cornish involvement with mining in Cuba, as the deposit was open casted until its closure in 2001, which has destroyed virtually all of the industrial archaeology.

Further Reading

For more information and references, see S.P. Schwartz, The Cornish in Latin America: ‘Cousin Jack’ and the New World (Cornubian Press, 2016).

I am in the process of writing a book entitled The Cornish and the Copper Mines of El Cobre, Cuba. If your Cornish ancestors worked there, I’d really love to hear from you!

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2022.

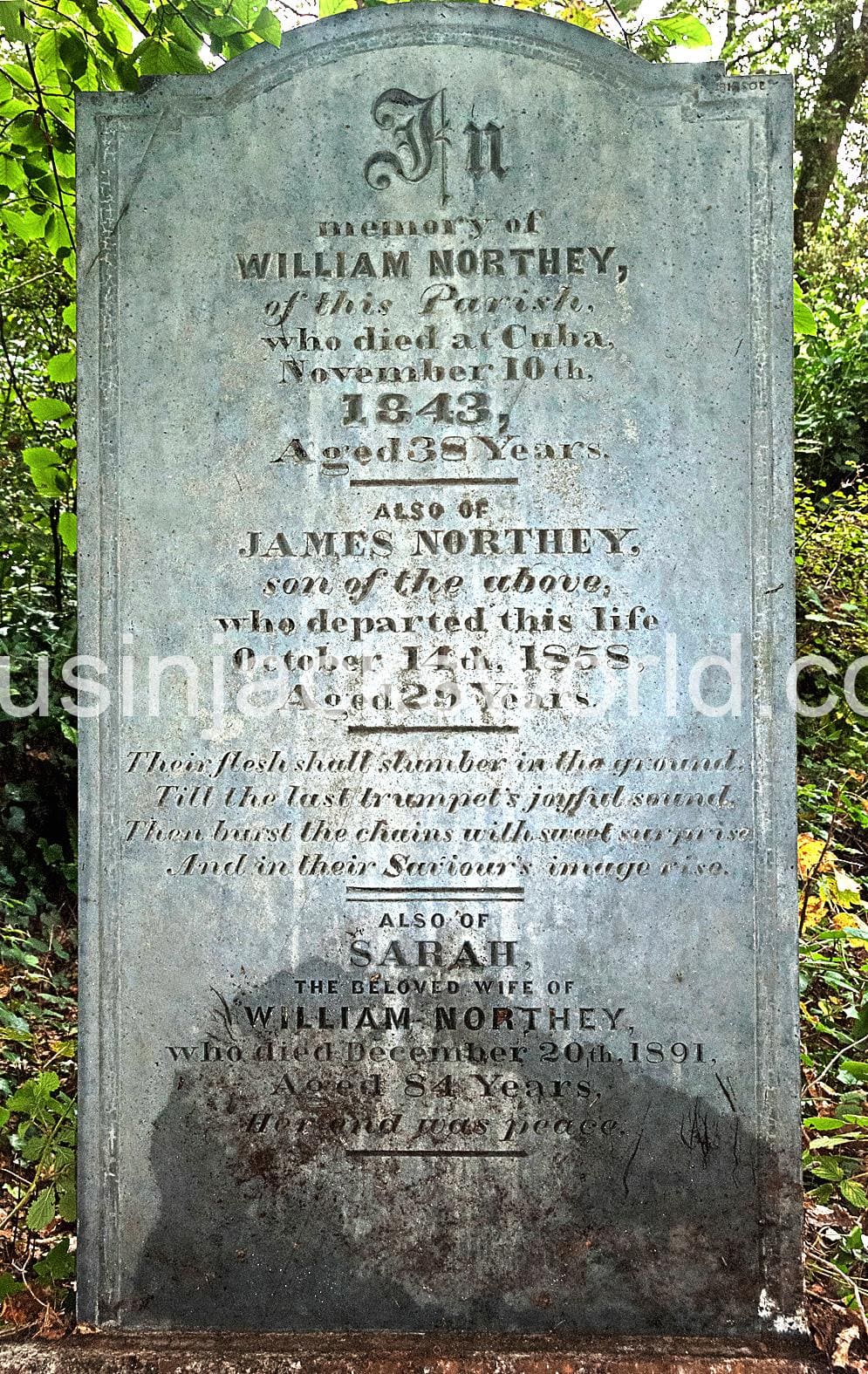

Hi Sharron. I have found out that my great grandfather was born in Santiago, Cuba on 24 May 1863. He also spent some time in Demerara, British Guyana. He became a mariner and then ships cook for commercial sailing vessels between USA and Liverpool, UK. He then married and settled in Liverpool. I also know that his father was Joseph Evans Northey and I am still trying to find his records, which I assume will point to him coming from Cornwall and emigrating to Cuba in the 1860’s.

It would be good to hear if you know more about this ‘Northey family’ and their exploits in Cuba and Guyana. Thanks, David Northey (in Wales, UK)