Kawau Island, New Zealand

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021, and may not be reproduced without permission

Kawau Island: An early Cornish Mining Community in New Zealand

Kawau Island lies about 49km north of Auckland in the Hauraki Gulf, and is the site of one of New Zealand’s earliest mining ventures. It later became the island home of Sir George Grey, one of New Zealand’s most influential and controversial political figures.

About ten per cent of the island is protected as a publicly owned historic reserve, part of the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park, administered by the Department of Conservation. The remainder of the island is privately owned with a small resident population. Ferries travel to Kawau island daily from Sandspit Wharf, near Warkworth. In summer, ferries operate from downtown Auckland.

Kawau was purchased from the Māori in 1840 by an Aberdeen-based investment company for farming purposes. Manganese and copper were discovered shortly afterwards, and for a short time, Kawau was the most productive mine in New Zealand, with a resident mining community that had a strong Cornish contingent. Two distinct phases of mining occurred: 1843-55; and 1898-1900.

From Farming to Mining

‘Kawau Paka’ is Māori for the white-throated or little shag-cormorant, a bird often seen around the island’s shores. The name reflects the island’s Māori heritage. For three centuries Kawau Island was occupied by the people known as Ngāti Tai who were later defeated by the Te Kawerau iwi. The island was eventually abandoned in the 1820s after a particularly bloody skirmish between warring Māori groups.

In 1840 the island fell into the orbit of the North British Australasian Loan Company, an Aberdeen-based company which was formed in 1839 for the purposes of investing money in the purchase of land and sheep. The original capital was £50,000 in shares of £1 each. Its directive was to turn a profit which would be returned to the largely middle-class investors in Scotland. James Forbes Beattie, a land surveyor and the company’s Manager in the Colonies, hired Henry Tayler to help purchase Māori land as an investment in New Zealand. After protracted debate over ownership, in 1840, W. T. Fairburn, acting on behalf of Tayler, purchased Kawau Island from the Crown for the North British Australasian Loan Company for the sum of £197.9.0.

In 1842 John Aberdein, another company agent, was sent to the island to investigate the possibility of establishing farming and pastoral settlements there. The Company soon introduced cattle, sheep and donkeys to the island. Interestingly, the donkeys were the first to ever arrive in New Zealand. But these plans were altered when minerals were discovered.

Mining on Kawau began in 1843 following the accidental discovery of manganese at Manganese Point near North Cove. In May 1844, a cargo of this ore arrived in Sydney from Auckland via the Tryphena. At this time, frenetic prospecting activity was taking place throughout the region, and copper and/or manganese deposits had been discovered on Waiheke Island, Coppermine Island in the Hen and Chicken Islands, and on Great Barrier Island.

In spring 1844, copper ore was discovered at South Cove by Alexander Kinghorn, the Superintendent of New Zealand’s first copper mine, which was being wrought on nearby Great Barrier Island. An overjoyed Tayler wrote to Beattie of the promising copper discovery, and could barely contain his excitement at the news that the place was thought to be worth from £20-80,000.

In the belief that this copper deposit would revive the fortunes of the Scottish investors, the North British Australasian Loan and Investment Company formed the Kawau Mining Company as a subsidiary company under the control of Mr Beattie. Beattie, who was the immediate grantee of Kawau Island from the Crown, authorised a conveyance to another company agent named John Taylor, making him a tenant in fee simple of the island.

John Taylor was instructed to engage a professional copper miner and to employ some miners to begin working the mine. Thus, on 7 September 1844, John Aberdein made an agreement (on behalf of Beattie and Taylor), with seasoned mineral prospector, Isaac Merrick, to undertake the mining of copper ore on Kawau Island.

Taylor inspected the workings in November 1844, shortly after the mine had opened, and then returned to Sydney, reporting to Mr Beattie that the copper prospects were good. His advice was passed on to the investment company back in Scotland where it was well received, and the capital was increased by £50,000 to £100,000 to facilitate mining development.

Notwithstanding the disadvantages they laboured under, from want of proper tools and knowledge of hard rock mining, the men employed by Taylor raised 750 tons of ore. The ores sold at Swansea during 1845 averaged around £11 12 s 5d per ton, and had not been selected by an experienced miner.

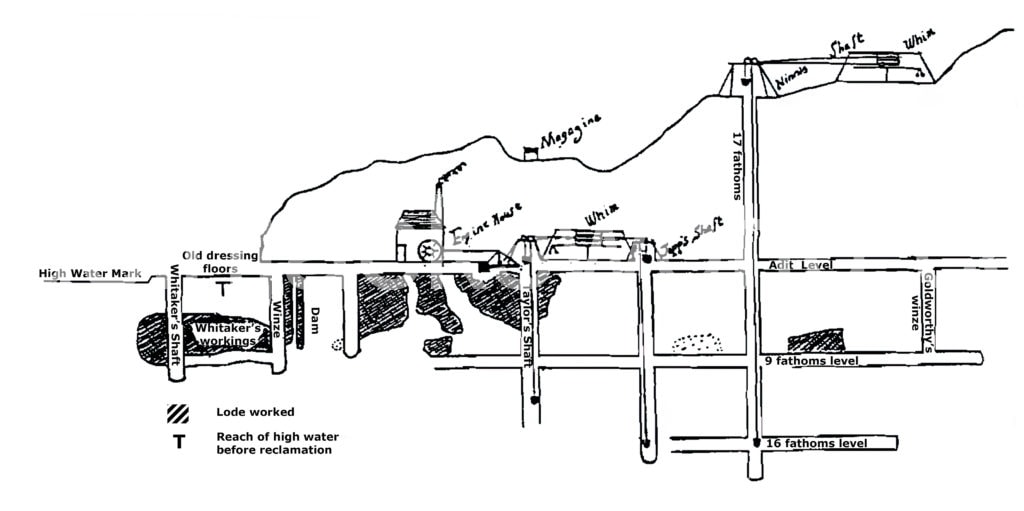

The copper lode ran roughly north-south, outcropping on a steep spur on the coast where the main mine adit was located. The cliffs hereabouts were blasted and the rubble used to create an area of reclaimed land separated from the sea by timber piling. This provided a platform for ore dressing and several copper ore hutches were constructed to store the ore prior to shipment from a nearby jetty. This reclaimed land, however, proved to be something of an Achilles heel for the Kawau Mining Company.

The Cornish Arrive at Kawau

Despite the promising early start, it soon became evident that skilled labour was required to further develop the mine. The company therefore recruited a group of Cornish mineworkers headed by Captain James Ninnis (1809-1879), a native of Goonvrea, St Agnes, who had enjoyed a peripatetic career as a Mine Agent in various mines in Cornwall and at Bere Alston, West Devon.

On 23 July 1845, Captain Ninnis and his party, which included miners and a carpenter, left from Falmouth on the Agostina with a proper supply of tools, equipment and machinery. The party arrived at Sydney in January 1846 where they were met by John Taylor, who accompanied the party to Auckland in the barque Isabella Anna. Captain Ninnis’s wife, Priscilla, one of his children and a servant, accompanied him.

Other passengers listed were: William ‘Billy’ Rowe (1816-1886) who had begun working in the mines of his native St Agnes at 10 years old, his wife Susanna and their two children (Susanna and Priscilla); J. Simmons; J. and W. Walters; J. Higgins; W. Baptist; and William Heath, his wife and three children. Captain Ninnis undoubtedly personally picked these men, as the Rowes were from his native parish of St Agnes, and the Walters’s were a father and son who had been living near him in Bodmin in 1841.

Something of Billy Rowe’s character can be gleaned from a letter sent during the long voyage by Captain Ninnis:

‘The weather has again been fine for several days and today we were again privileged with Divine service, then Mr Rowe gave us a very excellent discussion on the characters of ‘The Righteous and the Sinner’. He is often called the Parson but not always out of respect, but he does not seem to care for what men do say, he preaches Christ to all as the sinner’s friend, and pounds out in plain language the fearful consequences of a life of sin and open rebellion against God’.

The party finally arrived at Kawau on 14 January 1846, where Billy Rowe began work as a miner at £10 per month.

Getting There

Cornish mineworkers often left the Port of Falmouth on a ship bound for Sydney via Cape Horn. Some journeys began from English ports which became more the norm after Falmouth lost its Packet status in 1850. From Sydney migrants travelled by barque to Auckland and then proceeded by boat to Kawau Island. This was among the longest voyages endured by emigrant Cornish mineworkers in the mid-1800s.

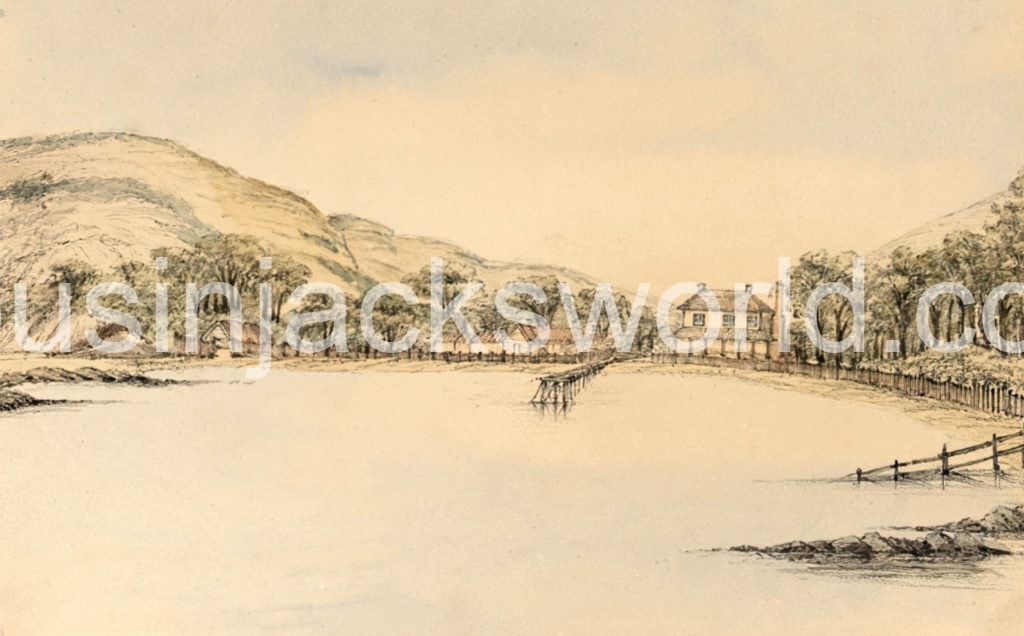

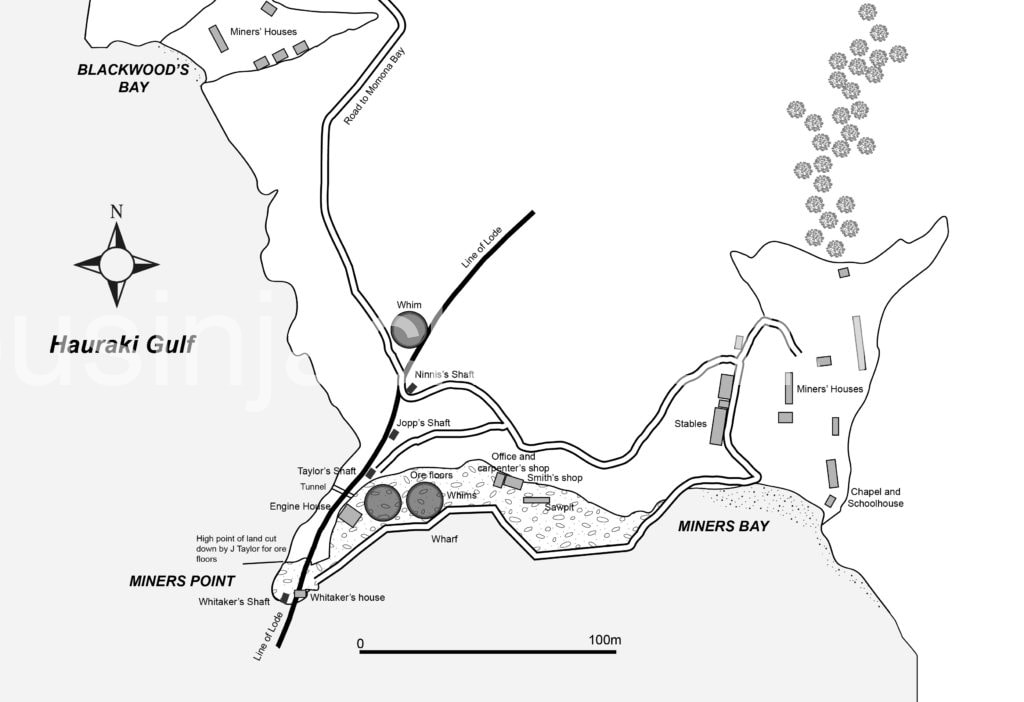

New Zealand’s First Significant Cornish Mining Community

The Kawau Mining Company spent around £23,000 building mining infrastructure, and creating a village for the miners and their families at Monoma Bay (later renamed Mansion House Bay). In 1845, tenders were called for the construction of a red brick house and offices consisting of eleven rooms at Monoma Bay for the future Mine Agent, Captain James Ninnis. This was sited at the chief mining settlement, consisting of company offices, assay house, stables and surgeon’s house. A street with timber houses on either side was laid out for the mineworkers and their families. This ‘English’ village was served by a jetty.

Additional settlements sprang up elsewhere on the island. These included Two House Bay, Sunny Bay, Dispute Cove, Schoolhouse Bay, (where the island’s first school was built in 1845, but destroyed by fire soon after), and Miner’s Bay, a large settlement that was just to the east of the mine workings, and close to another block of stables where the horses that drove the whims were located. By 1848 there were about 220 people on the island, and numerous children were born to their Cornish parents at Kawau.

The island community rapidly acquired a strong Cornish character. Captain Ninnis and Billy Rowe were both ardent Wesleyan Methodists, and a Chapel and new school house were soon built at Miner’s Bay. The Chapel quickly became the heart of the Cornish community, and Billy Rowe generally preached there twice every Sunday.

As many of the immigrant Cornish had their families with them, a flourishing Sunday School was established. The Chapel hosted various events, including Wesleyan Mission meetings, and bazaars in aid of the Auckland Wesleyan Chapel, which no doubt gave expression to the Cornish ladies’ organisational skills.

To counter the malign effects of Sabbath breaking and the evils of intemperance on Kawau, a Total Abstinence Society was set up in 1846, with Billy Rowe acting as its passionate and energetic secretary. This met with considerable opposition at first, but within a year 104 people had taken the pledge, and the scenes of drunkenness, riot and debauchery that greeted Captain Ninnis on arrival had been much reduced. Annual public tea parties associated with the society were held at the schoolroom, and visits were made by the Lord Bishop of New Zealand and the Rev. G. Daniel, a Wesleyan Missionary.

A cemetery serving the community at Boyd Hill was badly damaged by fire in the late-1880s. Cornish inhumations include Ellen Ninnis, the baby daughter of Captain Ninnis who was born and died in 1851, and Priscilla and Susan Rowe, the daughters of Billy and Susanna Rowe, who both died at Kawau in 1846.

Inflammable Issues

On arrival at the mine, the Cornishmen were kept busy building houses and sinking new shafts. By mid-March 1846, Captain Ninnis had set eight men to work driving a very well-defined lode, and an assaying house had been built to enable the copper content of the ore to be scientifically ascertained. It was found to average about 20-25 per cent of copper, with some parcels as high as 50 per cent. The dressed ore was sent to Sydney as ballast.

The Kawau ore body is contained in silicified greywacke and dips downward at a high angle. Beneath a well-weathered gossan cap is a leached horizon of variable thickness. Beneath this is a 20-metre thick rich oxidised zone, where copper from the weathered ore above has been transported and re-deposited. This then gives way to a 40-metre plus secondary sulphide enrichment zone, containing up to 12 per cent copper, and below that is a zone of primary copper ore, with a value of 1–2 per cent. The primary ore consists of massive pyrite with stringers of chalcopyrite and other minerals.

Problems began to occur when the company commenced transportation of the unaltered primary ore. In 1847, it was discovered that when released from the underground pressure and exposed to the air, it was prone to an exothermic reaction leading to spontaneous combustion. Conveying this ore in the holds of wooden sailing ships obviously presented grave dangers. Indeed, three cargoes of ore bound from Auckland to Sydney had to be jettisoned at sea, while another ship that had left Sydney for Portland Bay in New Zealand carrying Kawau ore as ballast, had to put into Launceston due to fears of a fire. As a result, the company began stockpiling Kawau ores in Australia.

To overcome these problems, in November 1848 the company decided to build a smelting works on Kawau fuelled by coal imported from Newcastle, NSW. The intention was to produce a regulus with a copper concentration of around 30 per cent. The resulting regulus blocks (around two cubic feet in volume), could then be safely shipped directly to Swansea for final refinement.

The company chose a bay dubbed Smelting Works Bay on the north side of the island as the location for the smelting works, and it was linked to the mine site by a cart track. Construction began in 1849 on two calcining furnaces, followed by the building of four flowing furnaces. A party of smelters was recruited at Swansea under Mr Jones, to man the new works. For six months the Welshmen experimented with smelting stockpiled Kawau ore at Port Jackson in Australia, before arriving at Kawau.

Operations at the smelting works produced quantities of sulphur dioxide fumes as the sulphide ore was smelted. To avoid the noxious fumes, the Welsh workers and their families built a colony away from the works, which they nostalgically named Swansea Bay.

However, more incendiary issues had been brewing at the mine for some time. The exciting discoveries of copper ore at Kawau and Barrier Island had attracted much attention in the contemporary press, and that of a devious lawyer named Frederick Whitaker. In exchange for a land allotment (No 16) in Auckland Town, which was wanted by the Surveyor General to build a defensive fort on Albert Hill, Whitaker and his colleague, Theophilus Heale of Auckland, succeeded in getting their friend, Governor Fitzroy, to grant them 36 acres of land between the high-tide and low-tide marks at Kawau Island. This parcel of land which they held as tenants in common under a Crown grant, was adjacent to the Kawau Mining Company’s workings, and on land that they had reclaimed from the sea to enable their mining operations to be conducted.

Whitaker and Heale lost no time in commencing their own mine. Their Superintendent, John Long Heyd’n, proceeded to cut down the ore hutches and dressing platform erected by John Taylor and to move about mine rubbish which obscured the precise location of the original high-tide mark. A shaft was sunk just above the water’s edge in order to mine the same copper ore lode as the Kawau Copper Mining Company. According to custom returns, up until 17 November 1846, Whitaker and Heale had already exported 469 tons of rich copper ore valued at £7,840.

Very soon suspicions grew that in addition to exploiting their submarine workings, Whitaker and Heale had begun to drive levels inland, and were encroaching on the Kawau Mining Company’s property. Billy Rowe swore that he could actually hear Whitaker’s men breaking ore very close to a pillar of ground containing rich copper ore. This had been deliberately left intact to protect their workings, as Whitaker’s Shaft was only protected from the sea by a timber collar at the surface, thus exposing the Kawau Company’s mine to the risk of flooding should the workings have been holed through.

Protracted litigation ensued for two years as the Kawau Company desperately sought an injunction to stop the theft of their ore, and to prevent Whitaker and Heale from working in a manner that was prejudicial to their own mine. Captain Ninnis actually entered Whitaker’s mine in June of 1846 and dialled the workings. He judged them to have already encroached 10 feet beyond the high-water mark.

In order to prove their deception, John Taylor ordered his men to drive the workings towards the sea to within a few inches of Whitaker’s workings, which were by now 12ft inside the company’s boundary. Captain Ninnis went down the mine to knock down the last thin wall of rock with his own hands to catch Whitaker’s men red-handed in the act of removing the Kawau Mining Company’s ore.

The Kawau Mining Company had petitioned Governor George Grey, who had replaced Governor Fitzroy at the end of November 1845, and via their London agent, they also petitioned Gladstone on the injustices they had sustained. Gladstone forwarded a copy of the Kawau Mining Company’s complaint to Governor Grey with the opinion that if their statements were true, the company had every reason to complain.

Governor Grey agreed and after taking advice from the Attorney-General, in 1847 an application was made to the Supreme Court successfully repealing the Grant to Whitaker and Heale. The Court recommended that the land between high and low water be included in the grant to the Kawau Company. This was carried out, defining the title boundary of Kawau Island as the mean low water mark, much to Whitaker’s chagrin.

However, the Company’s legal headaches didn’t end there. In 1849, the very future of the mine lay in the balance, as Governor Grey instructed the Attorney General to sue out a scire facias against the Kawau Mining Company. A similar ruling had already caused a cessation of mining activity at Whitaker’s mine, and a 12hp steam engine that he had brought out to Kawau in the Elora in the summer of 1848 had not been installed (and it appears, never was). The Kawau Mining Company had already spent between £30-50,000 building surface infrastructure. This had included sinking 4 shafts (Taylor’s Jopp’s, Ninnis’s and Shand’s); erecting a 12hp rotative engine in 1847 on Taylor’s Shaft to keep the mine workings dry; and the construction of a very costly smelting works.

Now they feared that their Crown grant might be withdrawn, the reason being, that when New Zealand was attached to the government of New South Wales, an ordinance was made by Sir George Gipps ‘that no white man could alienate from the natives to himself a greater quantity of land than 2,560 acres’. The Kawau grant was in favour of the manager of the Company (Taylor), to whom it belonged, and by this means gave the fulcrum to the Executive to try and deprive the Kawau Mining Company of their holding. Fortunately, matters were settled in favour of the company.

All of the legal wrangling and negative publicity that this generated caused the shares of the North British Australasian Loan and Investment Company to plummet, and at one time they were selling for as little as 10 pence each. The situation wasn’t helped by adverse publicity in prestigious publications such as the Mining Journal, which began to question the competence of the Kawau mine management, accusing the board of shameful mismanagement, and suggesting that they should concentrate on the farming side of their business. Their blushes were spared somewhat by the announcement in October 1849 of a discovery of rich copper ore at the Bon Accord Mine in which they held a third share. This property adjoined the famous Burra Burra Mine in South Australia, which caused their shares to rally.

However, Whitaker and Hearle, who recommenced mining operations, kept up a feud about their rights for years with the Kawau Mining Company, and their agents retarded the company’s operations at every opportunity. Eventually, Whitaker managed to secure £5,000 to stop his operations in order to save the Kawau Mining Company from destruction. Crucially, the act of taking down the protective pillar of rock between the two mines to uncover Whitaker’s deception led to the flooding of both mines when the timber collar on Whitaker’s Shaft inevitably failed.

A New Beginning: Mining Resumes on Kawau Island

In 1851, Captain Ninnis left Kawau, probably at the same time as Billy Rowe. Both men remained in New Zealand, and after several years operating a carrier’s business together in Auckland, they took on the management of the Great Barrier Mining Company. They were later associated with the Waikako coal mines and the Karunui Mine at Thames. Ninnis became involved in the manufacture of flax in the 1860s, and was jointly the owner of New Zealand’s first patent for a machine used to manufacture rope and woven fabric. He later returned to mining as Captain of the Kapanga Mine on the Coromandel Peninsula. Rowe later captained the famous Caledonian Mine at Thames, and was returned to the House of Representatives, serving from 1875-79, where he was an acknowledged authority on mining matters.

Ninnis’s position of Mine Captain was filled by a German metallurgist named Beeger (variously spelt Berger or Begher). He made modifications to the smelting works, replacing the Welsh method for a simpler and cheaper German process. He immediately encountered problems in retaining men at the mine due to the irresistible lure of the gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia, and was consequently forced to pay higher wages to keep men at Kawau.

As the mine approached the 24-fathom level, the water ingress began to overwhelm the 12hp steam engine. Plans were made to improve its power by building a flue to a new chimney higher up the ridge above the mine to increase draught to the boiler. But it was too little too late. The lower levels of the mine continued to flood and working was suspended in 1852.

But Beeger was not about to throw in the towel. Over £40,000 of copper ore had been raised from a depth of only 24 fathoms, and he believed the mine still had a future. He set sail for Aberdeen to convince the Board of Directors of the necessity of injecting sufficient capital to purchase a more powerful steam engine to solve the flooding issues.

His plea didn’t fall on deaf ears, and in order to better effect their mining operations, the North British Australasian Loan and Investment Company recruited well-known consulting engineers, Messrs. John Taylor and Sons of London, as the managers and cashiers of their mining affairs. The company was renamed the North British Australasian Company with its head office in London, and 65,000 new shares of £1 each were floated on the London Stock Exchange to raise the necessary capital to revive the fortunes of the Kawau Mine.

Beeger had travelled to Cornwall, probably on the advice of Messrs. Taylor who were great advocates of Cornish steam engine technology and Cornish labour, to recruit the men, machinery and equipment that would usher in a new era at Kawau. A powerful 36-inch cylinder engine capable of draining the mine to the 80-fathom level was purchased in Cornwall. It is not known whether this was a second-hand engine, or one that was purchased new, possibly from the Perran Foundry. A new barque named the Baltasara (330 tons register) had been purchased by the company to convey the company’s ores to Swansea.

The Baltasara sailed from Falmouth on 9 September 1853 with the steam engine, a complete set of pitwork, mining implements and stores, accompanied by a portion of the mining staff. Some of these men had their wives and children with them and their names were as follows: S and Mary Elphick; W.G. Sedgwick his wife Charlotte and daughter Charlotte; Captain Anthony Bray, a copper Mine Agent from Sunny Corner, Gwennap, and his two sons, John and Anthony junior; Josiah, Phillip, John and Henry Jeffrey; Jeremiah and Edwin Blight; miner William Whitford and his wife Alice, a newly married couple from Carharrack, Gwennap; Thomas Bray, a miner from Carharrack, Gwennap, with his wife, Harriett, and daughter Harriet Jane; William and Catherine Edwards; miner William Williams, his wife Caroline and their daughter Caroline; James Vigus; Thomas and T.A. White; N. Chennalls; James Dean; John Hancock; Daniel Blamey; William Skewes; J.B. Ward; Sarah Thomas and A. and G. Allen.

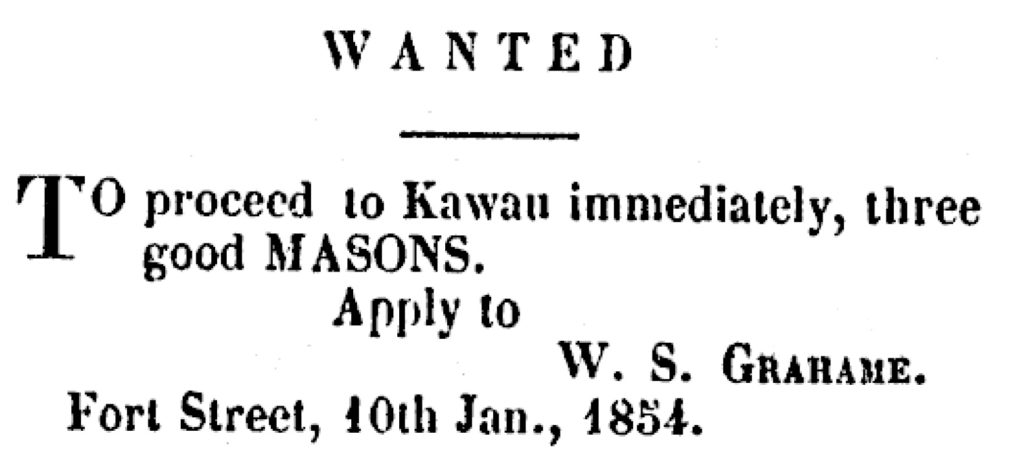

Another party of recruits (14 in number), had already left Gravesend on 14 June 1853 on the Joseph Fletcher which arrived at Auckland on 30 September. On 14th October, a vessel named William left Auckland for Kawau with the 14 miners, 4 women and 2 children. On arrival, this party were engaged in readying the mine buildings in preparation for the second party’s arrival. The Baltasara arrived at Kawau on 18 January 1854, where her precious cargo was discharged in excellent condition.

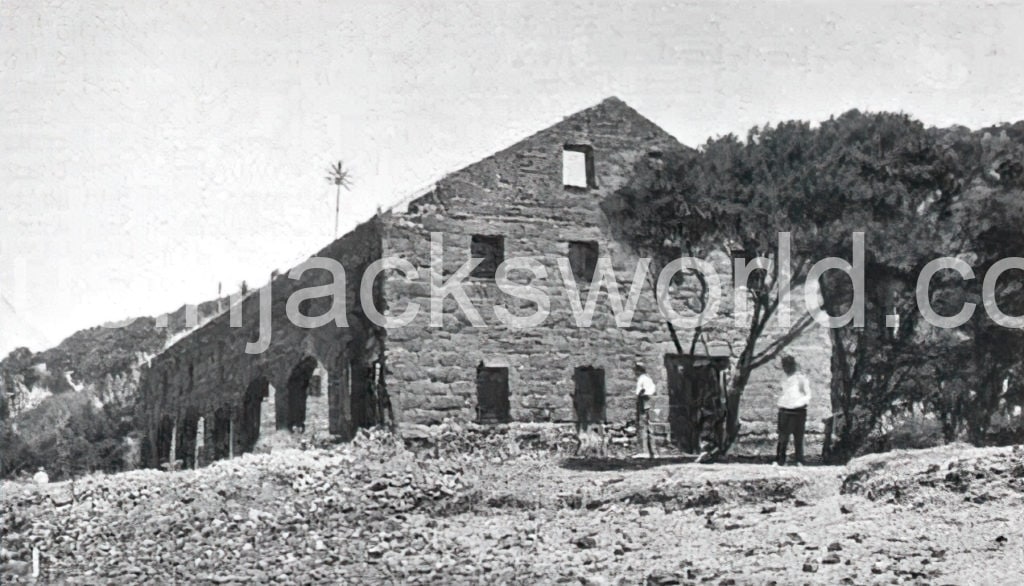

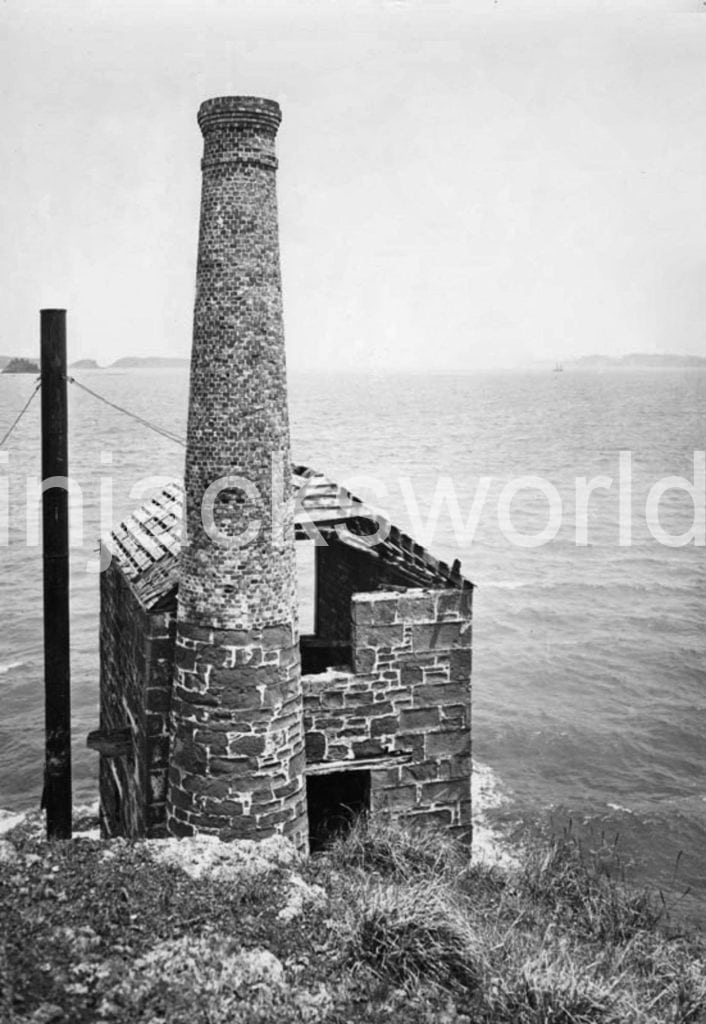

In January of 1854, the company advertised for 3 good masons to proceed to Kawau immediately, a sure sign that an engine house was being built on Whitaker’s Shaft to accommodate the new Cornish steam engine. This was constructed of sandstone blocks quarried at Matakana on the mainland, and despite delays due to poor weather, by late April 1854 it had been built to the level of the spring beams. The engine was started in early September.

On 9 February 1855, six more miners from Cornwall arrived at Kawau, and the following month Captain Bray commenced sending ore to the smelter. However, the ground at depth became harder, troublesome to work, and the ore was heavily mixed with ‘mundic’ (arsenopyrite) which made dressing it difficult. The poorer ores were cast aside as the cost of imported coal made it uneconomical to refine them. Costs began to escalate and further trials in the mine were suspended.

The 34-fathom level was finally reached in September 1855, only to find that the hard rock had completely impoverished the lode. Additionally, Beeger had grossly over-estimated the quantity of easily workable ore left standing at the 24-fathom level. Soon afterwards the Company’s Sydney agent began refusing to honour Beeger’s heavy drafts on the company.

In April 1856, the shareholders were informed at an ill-tempered meeting that Beeger had called time on the venture and was engaged in winding up the concern with as little further loss as possible. Over £28,000 had been expended in the second trial of the mine, and all that was to show for this was a shipment of 32 tons of regulus and a single dividend of 1 shilling in the pound.

By April 1857 the total loss on the property was estimated at over £78,000. In order to recoup some capital, the machinery had been stripped from the mine and placed up for sale, the barque Baltasara had been sold in London at a loss, and the new engine had been removed from its house and shipped back to ‘England’.

In fact, this 36-inch cylinder 8.5 foot stroke, equal beam engine, its associated pitwork and sundry items had been unloaded at Devoran in Cornwall, and was offered for sale by auction on 13th October 1856. What became of it is currently unknown.

With the mines’s closure, the Cornish community of over 50 people at Kawau was dispersed. Some of the men and their families, including Captain Anthony Bray and his sons, returned home to Cornwall.

Epilogue

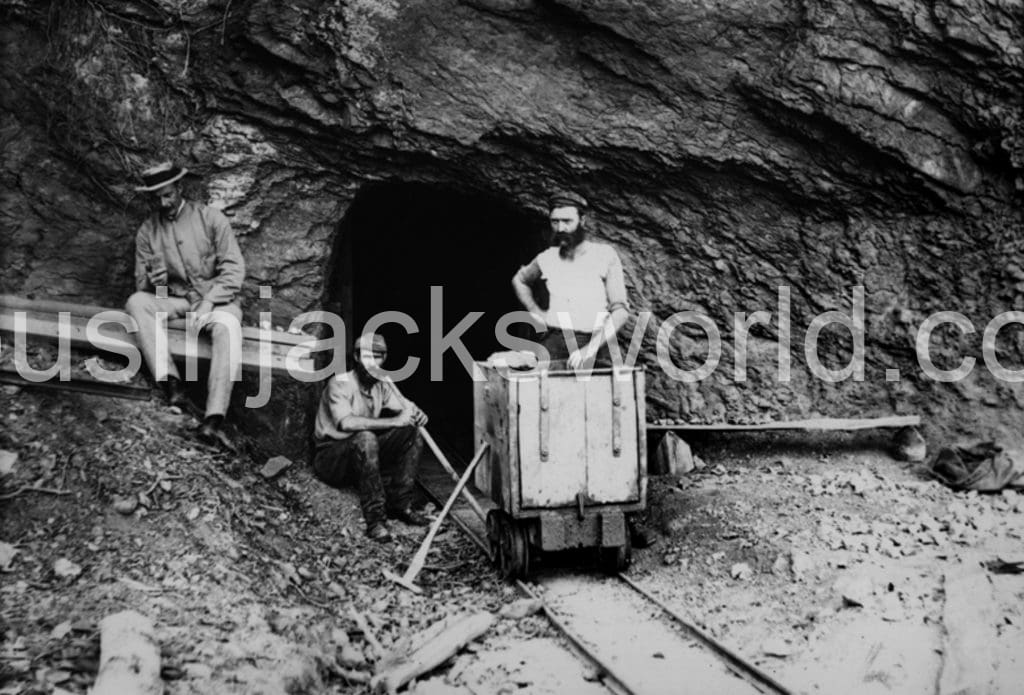

There was one last unsuccessful attempt to rework the mine by the then island’s owner, William Holgate, who in 1899 was noted to have raised a substantial sum to enable it to be opened up and worked, and the island prospected. This venture was captured in a series of striking images by photographer, Henry Winkelmann.

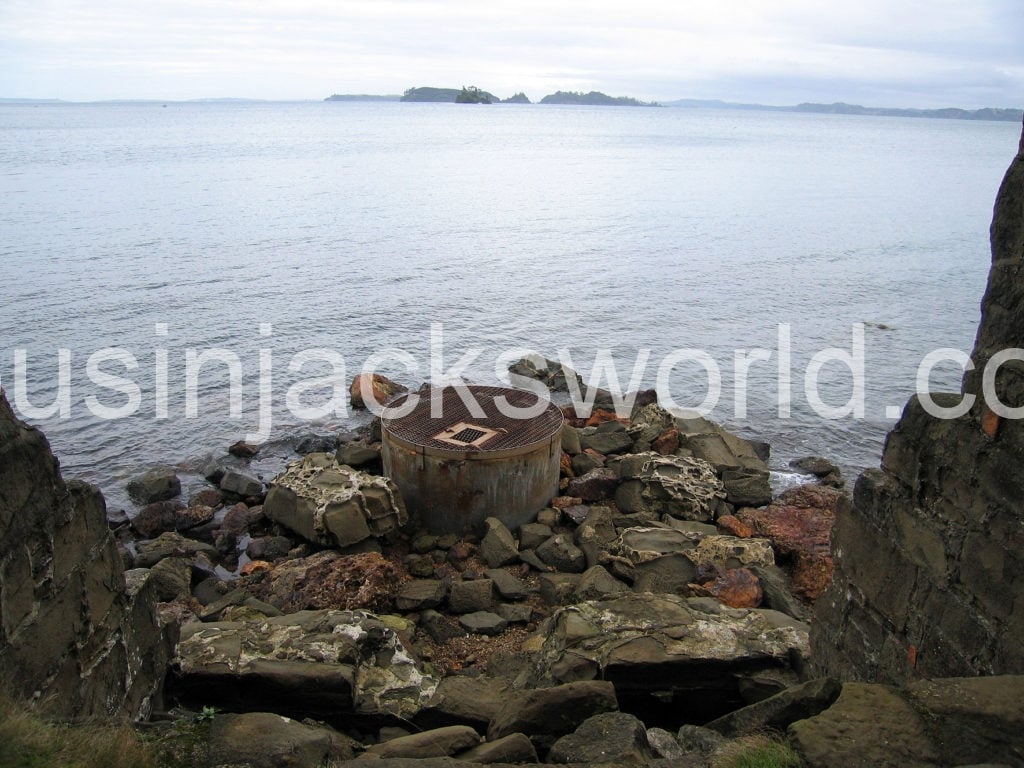

A horizontal boiler was brought to Kawau from A. and G. Price Ltd., engineers of Thames, to supply Cameron and Tangye steam jet pumps in Whitaker’s Shaft. However, no production resulted and the mine has remained flooded since.

Visit Kawau’s Industrial Heritage

In 1862, Sir George Grey purchased Kawau, taking Captain Ninnis’s old house as his residence. He embellished this building by adding a palatial new wing and landscaped gardens. Mansion House, a Category 1 Historic Place, has been in public ownership since 1967. The mansion and its historic jetty built for Sir George Grey in 1875 (believed to be the oldest New Zealand) have been extensively restored to their former appearance.

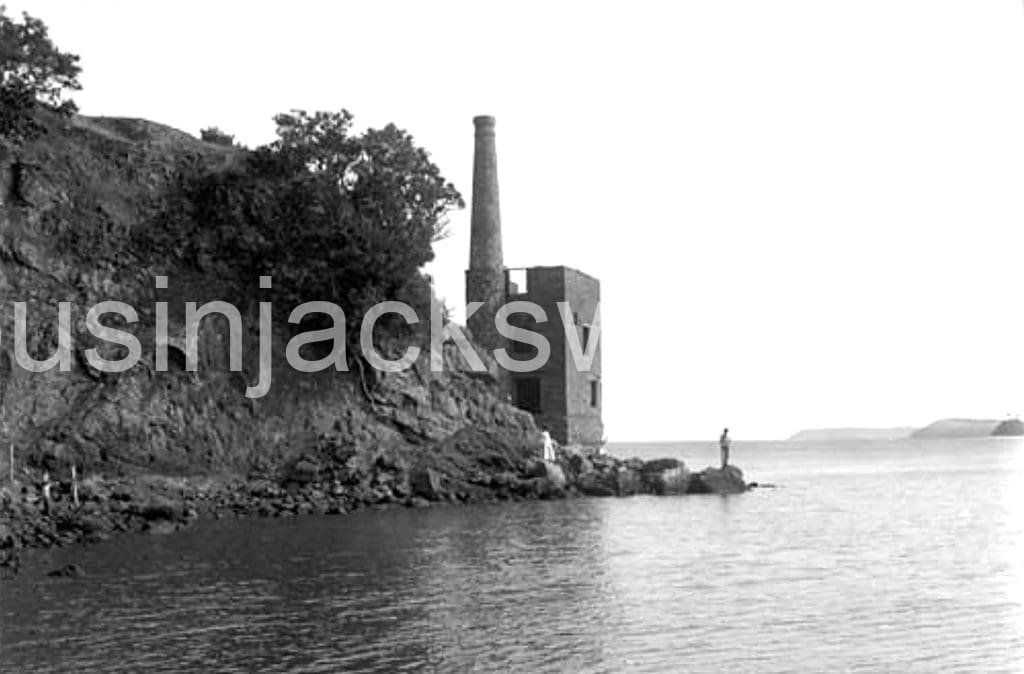

I visited Kawau in July 2005, and the rusting horizontal boiler used by William Holgate can be seen in front of the old adit behind the truncated remains of the Cornish-type engine house on Whitaker’s Shaft. This is marked by a concrete pipe collar surmounted by a precast circular cap just above the water mark. The Cornish-type engine house dramatically sited just metres from the sea must surely be the only one anywhere in the world to have been built so close to the water’s edge.

Very little remains to be seen at the surface of the mine, but archaeological excavations have unearthed one of the whim plats and a series of wooden structures with stone hearths in and near Miner’s Bay.

The Smelting House Historic Reserve on the north side of Bon Accord Harbour can be visited by boat, and some archaeological excavations at the smelting works have taken place. A busy industrial complex and village which once stood on this site, is now marked only by the sandstone walls of the smelting house building.

Further Reading

Rod Clough, ‘The Archaeology of the Historic Copper Industry on Kawau Island: 1843-1855, 1899-1901’, Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology Vol. 9 (1991, pp. 45-48).

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021.