Bruce Mines, Ontario, Canada

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2022 and may not be reproduced without permission

The Call of the Copper: The Cornish at Canada’s First Commercial Copper Mine

The town of Bruce Mines is located on the Trans-Canada Highway on the northern shore of Lake Huron, and is around 50km east as the crow flies from Sault Ste. Marie, a city located on the border between the Canadian state of Ontario and the US state of Michigan. Toronto is approximately 460km to the west.

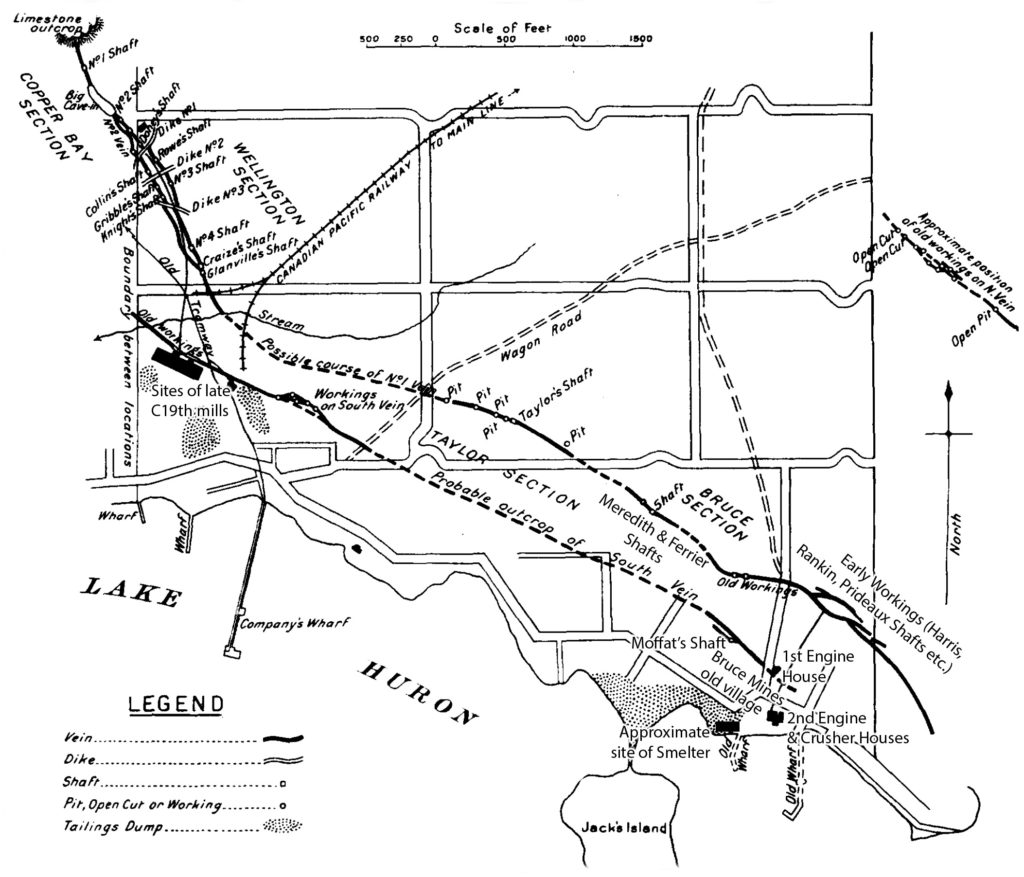

In 1846, rich copper ore deposits were discovered in what was then a very remote and isolated corner of Canada West (Ontario). The principal lode extends from the shore of the lake to the east of the old village of Bruce Mines for some 3km NW across the whole breadth of a greenstone outcropping. A series of mines in four distinct sections – Bruce, Huron Copper Bay, Wellington, and Taylors – were opened by various mining companies to work this, and other quartz-carbonate lodes, containing chalcopyrite and minor bornite and barite.

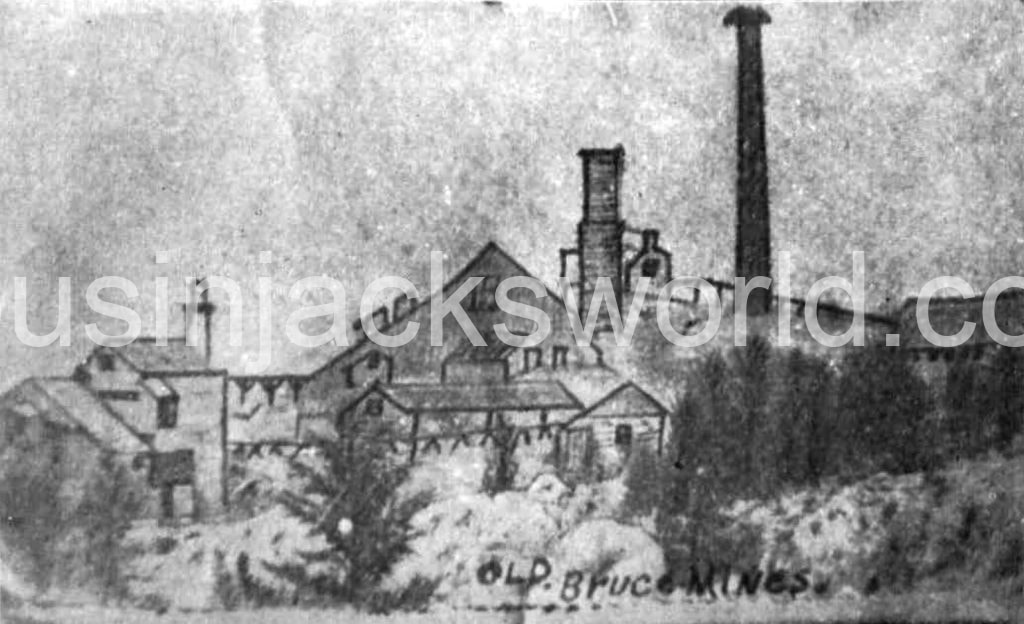

Bruce Mines was Canada’s first deep lode copper mine, and was only the second to be opened in North America, after the Cliff Mine in Michigan, USA. The mines utilised what was then state-of-the-art mining and smelting machinery, creating Ontario’s first large-scale industrial landscape.

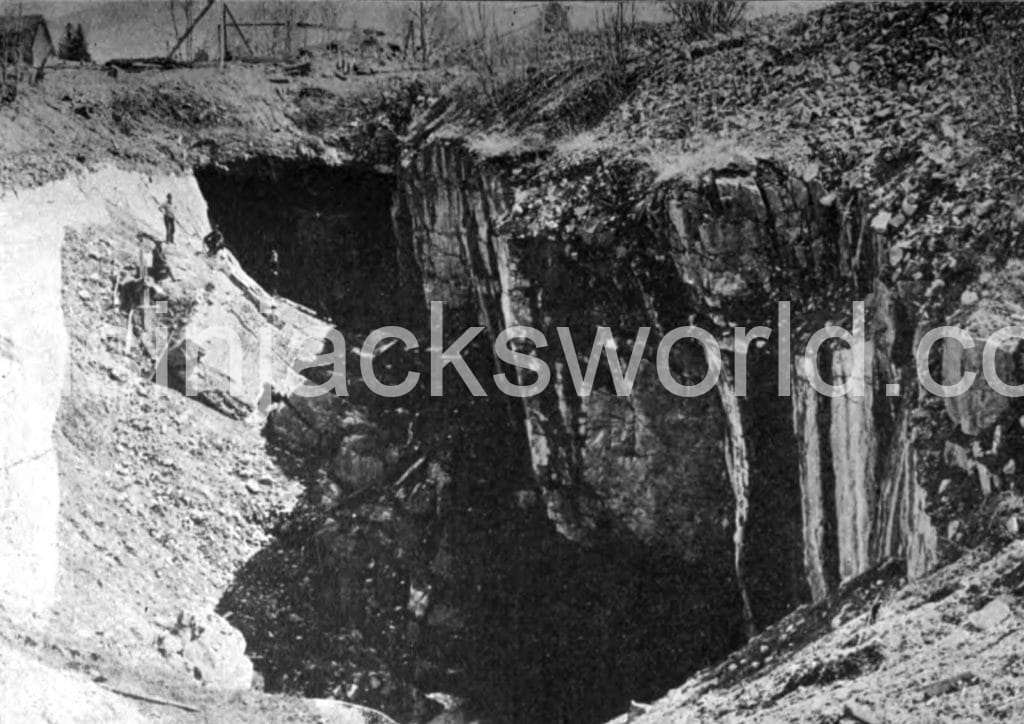

The shafts of some of the workings attained a depth of around 145m, considerably shallower than the average mine in Cornwall, and in places the ore was stoped out to surface. Where this occurred, the voids were housed with timber, rock, clay and earth. Although some of the timbers have since given way, remains of this work have survived in places.

The village of Bruce Mines, named after a former Governor General of Canada, James Bruce, was established to accommodate the mineworkers and their families. This community, which grew to around 2,000 people, had a significant Cornish presence, as they pioneered mining in the area.

The main period of mining was from 1846-76. Several attempts to re-open the mines in the early twentieth century saw only limited success, and they were decommissioned in 1944.

The Discovery of Copper

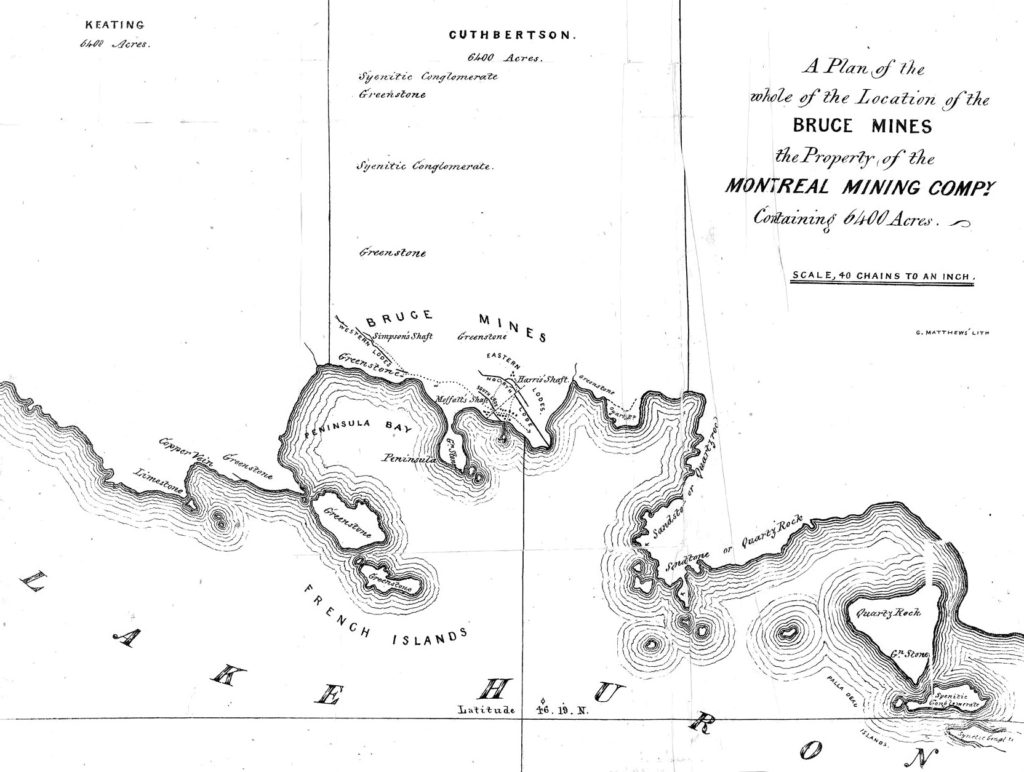

In the early-1840s, the discovery of incredibly rich copper deposits in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula prompted a wave of prospecting on the Canadian side of the border, where the copper deposits were thought to extend. In order to stimulate mining development and to secure revenue, the government of the new Province of Canada sold generous tracts of land each measuring 2 miles in front by five miles in depth for a total of 6,400 acres in the Upper Great Lakes region. Many of the purchasers were wealthy speculators who formed mining companies with interlocking directorates. However, the lack of sufficient capital, the remoteness of the region, the absence of transport infrastructure to support the mining industry, and land disputes with First Nations people, retarded initial mining development.

But Bruce Mines was an early success story. In the early summer of 1846, Captain John Keating (who was formerly connected with the Indian Department), was shown rich outcrops of copper ore on the northern shore of Lake Huron by the Ojibwa (the native inhabitants of the area) whose ancestors had been exploiting surface copper deposits throughout the region for centuries.

This land belonged to Montreal merchant, James Cuthbertson, who had applied for a license of exploration that year. The government was waiting on official reports of several surveys being undertaken to establish the mineral potential of the Lake Superior and Lake Huron regions, which delayed the issuing of licenses. Cuthbertson had therefore bought this block of land which was known as the Cuthbertson location, to prevent anyone else from making a claim.

In November of 1846, Cuthbertson, land surveyor Arthur Rankin, and Robert Stuart Woods formed the Huron and St. Mary’s Copper Company in Montreal to further explore what became the Bruce Mines area, and three other potential mine sites along the St Mary’s River. An Act to incorporate the company was passed on 28th July 1847 allowing £45,000 of capital stock comprised of 15,000 shares of three pounds per share.

Immediately afterwards, Captain Keating proceeded to Joseph Island with Arthur Rankin and an experienced Cornish miner, William Harris, to more closely inspect the copper outcrops at Bruce Mines. After spending two days on site, the party collected several blocks of ore and filled 16 barrels with ore specimens. Rankin took the last steamer from the Saute down to Detroit with the ore samples. Part of it was sent to Montreal and the remainder to Baltimore via New York for smelting. It was found to contain 20.5 per cent of copper.

Meanwhile, Captain Keating and Harris remained on site and began mining on 12 December with the help of four labourers. Despite deep snow covering the ground, they uncovered a lode about 2 feet 6 inches wide extending over a length of a least 40 feet. A stope 3 feet deep had been excavated, a shaft sunk 2.5 fathoms (about 4.5m), and about 60 tons of rich ore was recovered. A second lode of the same thickness and richness as the first had been found nearby, and a probable third lode had also been discovered on a ridge some 300 yards from the shore. Ore specimens that had been sent to Detroit had caused quite a sensation, and in March 1847 a delighted Keating wrote, ‘I would not give this location, which I think teems with veins, for any two on Lake Superior’.

Meanwhile, in 1846 Forrest Sheppard had undertaken a detailed survey of the northern shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron on behalf of the Montreal Mining Company. This company had been formed in 1846, and in 1847 had merged with the Canada Mining Company. Sheppard recommended the company’s acquisition of 16 locations, one of which was at Bruce Mines.

Captain Roberts, who had been engaged as the Company’s Mine Agent, visited the site in July of 1847. He was an experienced Cornish miner and the former Agent of the Connary copper mine in Avoca, County Wicklow in Ireland. He was moved to declare that the vast deposit of copper ore at the outcrop of the veins was incalculable and almost unparalleled: ‘It exceeds anything I have ever seen or heard of in Europe, and so strongly am I convinced of its value, that I would recommend that every possible means be adopted with a view to purchasing the mine, at even £100,000 if it cannot be accomplished for a smaller sum.’

As soon as the Huron and St. Mary’s Copper Company had proved the potential of the Bruce Mines, and a year after James Cuthbertson purchased the Cuthbertson location, it was sold to the Montreal Mining Company for 14,200 shares of their stock and £33,250.

The Huron and St. Mary’s Copper Company then focussed their attention on what became known as the Keating location in the Huron Cooper Bay section, which lay to the west of the area that the Montreal Mining Company was working. However, little seems to have been done there at this time.

Bruce Mines: The Cornwall of Canada

A mine and village quickly sprang up on the shores of Lake Huron in an area that was formerly almost untrodden forest. The climate is cold and temperate with relatively short, cloudy summers, and the winters are freezing, snowy, and mostly cloudy. The mercury falls to an average low of -7°C in January and Lake Huron can see ice coverage of around 50 per cent. In the mid-1800s, the provisions required by the mines over the winter months had to be brought in by steamers plying the route between Detroit and Saute Ste. Marie, before the seaways iced over.

Although the Bruce Mines area was rough and rocky, it had locational advantages. Vessels of any size could enter Bruce Bay, nearby forests meant that there was a ready supply of timber for fuel and mining purposes, and ample prairie land for growing food and fodder surrounded the settlement. A river immediately adjoining the property contained four falls of 4-13ft which made excellent mill sites, and a chain of canals connected Lake Huron with the Atlantic.

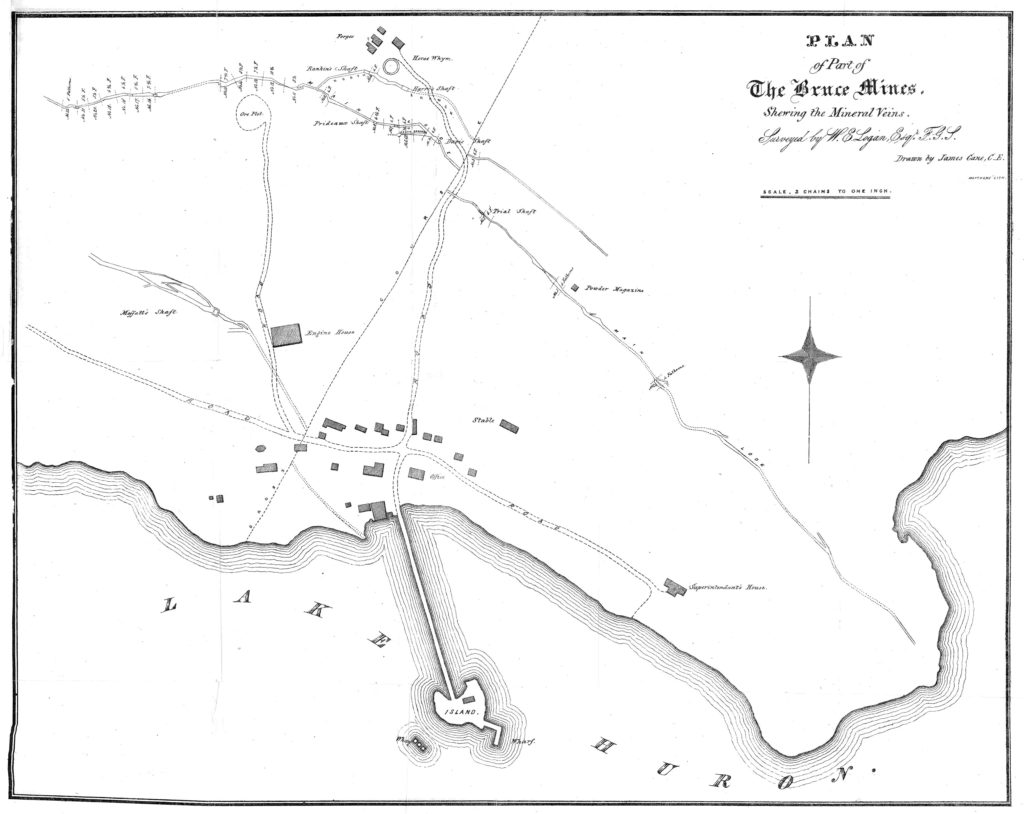

The Montreal Mining Company immediately set about building a plank platform road out to an islet where a wharf was constructed. Beyond this, three stone-loaded cribs were sunk for a further wharf to accommodate steamers and vessels frequenting the harbour. Close to the shore, timber frame buildings including an office, a warehouse, and stores were erected, and some 50 log houses were built to accommodate the mining population of around 250 people. From the water’s edge, the ground rose by gentle acclivity to one of the mines started by Keating and Harris which was some 70ft above the bay, and at a sufficient height to allow of the drainage in shafts at the 10-fathoms (18m) level.

Work clearing the ground and burning the brush had been carried on to a considerable extent by 1848. This was necessary not only to guard against fire, but also to prevent the great annoyance caused to the mineworkers by biting flies, which drove the men from their work on several occasions in 1847.

One of the lodes had been traced at the surface for over three quarters of a mile, and during 1847-8 over 1,400 tons of copper ore and undressed lodestuff was brought to the surface. The ores were sold in Baltimore. Many of the pioneer mineworkers were Cornishmen who had already made their way to the area from the Upper Mid-West lead mines of the United States.

The Montreal Mining Company was the first to introduce large-scale mechanisation into the Canadian hard rock mining industry. On the recommendation of Captain Roberts, a 30-inch cylinder Cornish steam engine with a 28-foot beam for crushing, dressing and pumping purposes arrived at the mines in 1848. This had been imported from Cornwall along with a consignment of ore dressing machinery (a Cornish rolls crusher and mechanised jiggers) and a battery of Cornish stamps. The engine had been manufactured at the Copperhouse foundry of Sandys, Carne and Vivian, and left the Port of Hayle on the 4 July 1848 on the barque Caroline bound for Montreal along with engineer, John Vivian. On board were 50 emigrants from Hayle and its vicinity.

This was a time of immense depression in the Cornish mining industry due to the unsettled political state of the Continent, and a lack of orders had resulted in men being laid off at the Copperhouse Foundry and its rival, Harveys of Hayle. It was a buyer’s market, and the Montreal Mining Company was pleased to have purchased the steam engine and other machinery at a price below what the foundry usually charged.

A further boon to the nascent mining operations at Bruce Mines was the availability of skilled labour due to unemployment in Cornwall as a result of the decline in the copper trade. This had induced men who would never have left home to migrate to Canada, and allowed the company to lower the enormous rate of wages they had been paying their workers since the mineral regions in Western Canada (Ontario) had been discovered.

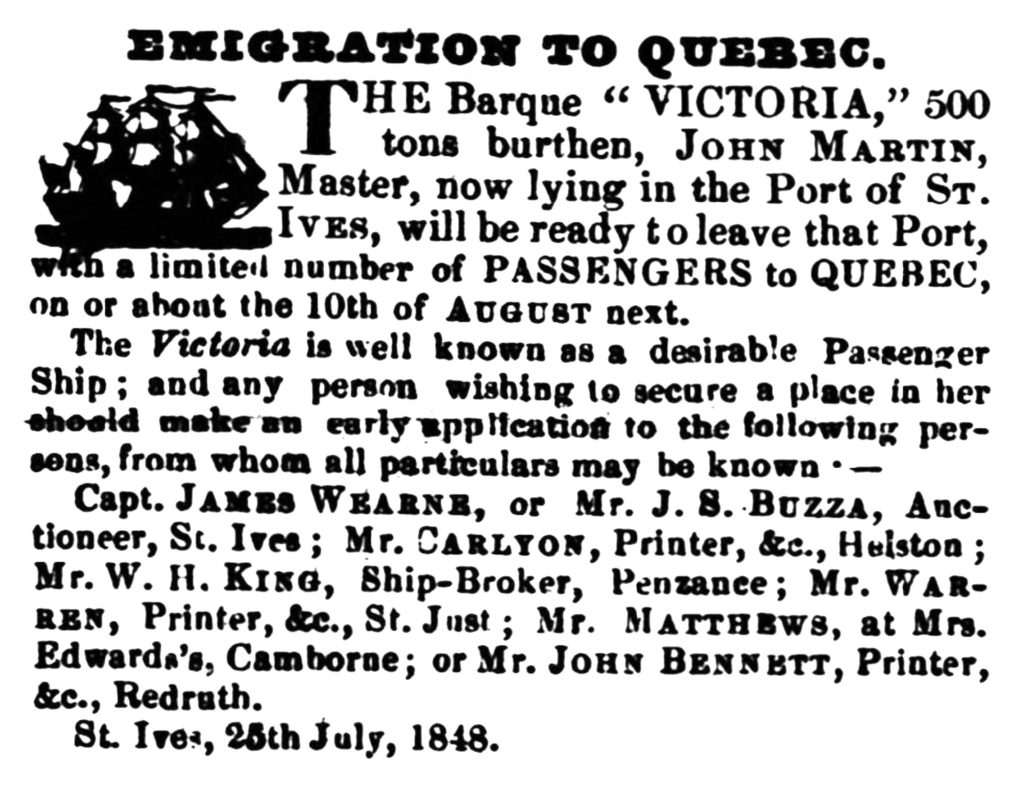

Indeed, the departure of the 50 Cornish mineworkers with the large consignment of mining machinery was noted in the local press:

So great was the respect and the sympathy felt for the emigrants, that a large concourse of people assembled on the wharf and on the Towans, to witness the departure of the barque, which was towed over the bar, and nearly across the bay, by the Brilliant steamer… When the tow lines were cast off, the whole of the passengers and crew of the Brilliant bade the emigrants adieu with three hearty and enthusiastic cheers, which were warmly responded to by those on board the barque. The hundreds of persons on the deck of the steamer, and the thousands on shore, constituted one of the most imposing sights ever witnessed at Hayle.

The Caroline arrived at Montreal in early October 1848, and the Montreal Gazette noted that many of the Cornish mining families were hoping to find employment in the Lake Superior mines. Some of these men were taken on at the Bruce Mines.

To avoid having to pay the heavy freight costs of sending the ore to be smelted at Baltimore or Swansea, the Company decided to build its own smelting works modelled on the Swansea system (using reverberatory furnaces). Mr Davis, head smelter, and three furnace men were brought over from Wales to help to erect the smelting works which consisted of 2 calcining furnaces, 3 melting furnaces, 2 roasting furnaces and one refining furnace. It was estimated 8 tons of copper could be produced in a week. The smelting works which stood on the lake shore around 50 yards west of the mine’s mill (see below) was fuelled by bituminous coal brought in by water from Cleveland, Ohio.

The Montreal Mining Company hoped that the state-of-the-art mechanised facilities it was constructing on the shore of Lake Huron would ensure that Bruce Mines developed into a regional concentrating and refining centre.

Getting There

Early Cornish migrants left aboard barques bound for Quebec City or Montreal, from a variety of ports including St Ives, Hayle, Restronguet, Malpas, Fowey, Padstow, and Plymouth. Later, people took steamers from Hayle to Bristol and thence to Liverpool for the Transatlantic crossing to Quebec City. From there, migrants travelled by railroad to Collingwood on the shores of Lake Huron, and then crossed the lake by steamer to Bruce Mines. Migrants coming from the USA took a steamer from Detroit to Sault Ste. Marie which stopped at Bruce Mines en route, a journey which took around 2 days.

Campbell’s Chaos

By 1849, Bruce Mines was home to nearly 300 people, over half of whom were employed by the Montreal Mining Company. However, the nascent community was hard-hit by cholera during the first weeks of September 1849, which claimed over 24 lives. So many mineworkers fell ill, that copper production ceased until cases began to wane in December.

On top of this, the validity of the ownership of the land being worked by the Montreal Mining Company at Bruce Mines was challenged by the Ojibwa people. In November 1849, a group of Métis and Ojibwa occupied a mine worked by the Quebec and Lake Superior Mining Association at Point Aux, Mica Bay, on Lake Superior. The mine was closed by its Superintendent and the mineworkers consequently departed unscathed, but rumours of a massacre there began circulating at Bruce Mines.

This caused great alarm, and the Montreal Mining Company’s President, George Moffat, requested a group of 100 men with arms and ammunition be sent to safeguard the mining operations. The men failed to reach there due to bad weather, but remained in Sault Ste. Marie until the following year, when the government concluded a treaty with the First Nations people and the situation was de-escalated.

However, these external influences were not the worst problems to beset the Company’s mining operations. The management was riven with disputes, and there had been frequent changes of personnel. Captain Roberts was the first to face the axe. His mining reports and forecast of operations were challenged after a visit by the company secretary, a banker turned lawyer from Scotland called Archibald Hamilton Campbell (1819-1909) who had arrived in Canada in 1845. In 1848 the Board of Directors consequently engaged the province’s geologist, Sir William Logan, to undertake a report.

In October of 1848 Captain Roberts was consequently fired for his ‘hasty and unguarded reports’ which were at variance with Logan’s findings. He was replaced by Walter William Palmer, a native of Devon, who had formerly worked as a surveyor with the Quebec and Lake Superior Mining Association. Cornishmen, John Semmens of Perran Downs, Perranuthnoe, was the Grass (surface) Captain, and William Harris, one of the underground Captains.

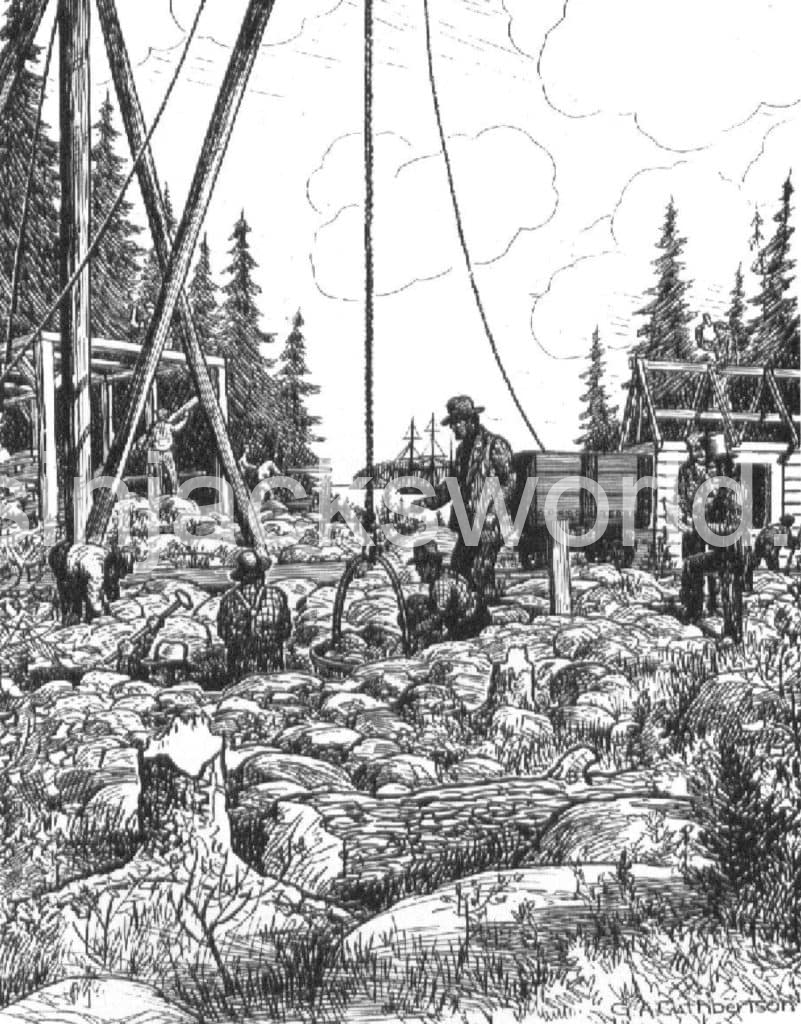

Campbell, who was promoted from Company Secretary to Mine Manager, also locked horns with engineer, John Vivian, and by all accounts treated him particularly badly. As well as operating pumps in Engine Shaft, the Cornish steam engine was to supply power to the mine’s mill, consisting of a Cornish rolls crusher, jiggers and concave buddles, at what was to become the mine’s primary dressing floors. As the engine house was the ‘frame’ for the engine, Vivian had to oversee its construction, along with the stack providing draught to the boilers, the boiler house and an adjoining crusher house, and then to manage the installation of the steam engine and other machinery.

Increased tonnages of ore were being raised to the surface, so Campbell made it clear to Vivian that it was imperative to get the machinery erected as rapidly as possible so that the ore dressing could be mechanised by the spring of 1849. This entailed constructing the engine house and auxiliary buildings in winter when the thermometer plummeted to -4°C, and the ground was frozen solid.

Severe frost and snow storms curtailed the building, and the extreme cold made it impossible to work outdoors, so progress was slow. To speed things up, and without consulting Vivian, Campbell wanted the top half of the engine house to be constructed of timber, but was forced to scrap the idea when he found that there wasn’t enough wood. The engine house, which was built 150 yards from the lake shore, was therefore constructed out of the local greenstone boulders to a typical Cornish design, and was probably the first of its type to have been built on a metal mine in Canada.

Campbell stated he was at first favourably impressed by Vivian, but gradually changed his opinion of him, describing him as ‘a headstrong man, threatening to give trouble’. The Scotsman, who had no training in mining whatsoever, resented the Cornishman’s ‘interference’ in mining matters beyond his duties as engineer, stating that the surface operations were the concern of Captain Simmons, and that ‘he [Vivian] must be managed and controlled until he is better acquainted with the climate and the manner of doing things in this country, or his English notions will entail upon us too much unnecessary expense’.

Vivian planned to build a reservoir located on a hill half way between the engine house and the mine to supply water to the engine’s boilers. But Campbell vetoed this. Vivian then resorted to sinking a shaft and an adit to supply the requisite water at a cost of £1,500, and Campbell acquiesced in this plan, although he later tried to claim the opposite. Work was retarded when a group of Cornishmen refused to take a bargain to sink the shaft at £25 per fathom. Moreover, Vivian had overseen the installation of enough engines in Cornwall to know that Campbell’s plan to work the pumps in a shaft some half a mile away via flatrods was not going to be successful.

Things came to a head when the ground began to thaw in late-February 1849 and the south west corner of the crusher house gave way. Alarmingly, the walls of the engine house were found to have settled a great deal, and fears for the stability of the structure prompted debate about whether or not the engine and machinery should be removed for safety reasons. Vivian was adamant that he had constructed an engine house that was well-built and fit for the purpose it was intended, but as soon as the machinery was set in motion it collapsed, killing a man.

Campbell tried to blame the calamity solely on John Vivian, when he had overall control at the mine, and then scrambled to build a new engine house and crusher house for the machinery. The new site was to the south of the collapsed engine house and nearer to the lake shore. This incurred considerable expense (over £2,000) and a loss of productivity to the company. He and the management then descended into a bitter blame game for the unfortunate state of affairs.

In July 1849, work on solid foundations for the new engine house which was 43ft high with external dimensions of 50ftx23ft, and a stack 54ft high, began with the placement of greenstone blocks weighing 3 tons apiece. Progress was retarded by the visitation of the cholera in the fall of 1849, causing some of the best miners, labourers and masons to flee Bruce Mines. The acute labour shortage was only remedied by the arrival of fresh hands from Toronto and Detroit, and experienced Cornish miners who had formerly worked at the Wisconsin lead mines and who had fled the disturbances at Mica Bay. The stone work was completed on 1 November 1849 and all the buildings were roofed before the onset of winter.

But the debacle with the engine house was only one example in a catalogue of errors perpetrated by Campbell. During his four-year tenure as Mine Manager, he spent nearly £100,000, leaving the company just short of £30,000 in debt.

He ordered company housing and stores to be built too close to the shoreline of the lake and these were subject to flooding as the level of the lake rose and fell. Despite having no ship-building experience, he hatched a hare-brained scheme to build a boat at Bruce Mines that would be used to convey freight on Lake Huron. This ill-fated vessel proved to be totally unseaworthy, and was nicknamed the ‘Wilful Murder’ by the inhabitants. It was eventually quietly retired to a bay near the smelting works. However, determined to have a vessel of some sort, Campbell then purchased a whaling boat in Boston which he had coppered and copper fastened, and which was delivered at the mines by railroad and steamboat at a cost of £175. It proved to be totally unsuited to journeys on the Great Lakes.

To avoid having to import firebrick and clay from Wales, he also ordered a brickworks to be built at great expense to supply the smelting works, when it would have been cheaper to import brick from Detroit. Finally, and rather surprisingly for a former banker, his book-keeping skills were also found wanting, and he refused to implement the Cornish tribute system, despite clear evidence that to do so would have been beneficial both to the company and the miners. The Montreal Mining Company’s financial future looked so bleak, that shareholders began offloading their shares, even going so far as to pay others to take these on, for fear of incurring heavy losses in the future.

As a direct consequence of his mismanagement, Mine Agent, A. Tregoning, a Cornishman with considerable experience of mining in Cornwall and Spain, resigned his position not more than 12 months into a 5-year contract, and the head smelter George Deer and his men who had been recruited in Wales around the same time as Captain Tregoning, also refused to remain at Bruce Mines, causing the smelting works to be shut up.

In the fall of 1850, Campbell realised that the game was up, and announced that he would be leaving the company to take a job as Manager at the Commercial Bank in Montreal. His position was filled by Edward Barnes Borron (1820-1915), who began his mining career in his father’s mines in Lanarkshire, Scotland, becoming the Manager at Leadhills in 1842. Another Cornishman, Samuel Tippett, replaced Tregoning as Agent. These men implemented the tribute system for ore dressing at once, and introduced the system underground shortly after.

A final stroke of ill luck occurred with the return of cholera at the end of the year, which incapacitated over a third of the workforce, claiming the life of Captain Penberthy, head of the tribute dressers, who was a great loss to the company.

Trials and Tribulations

Campbell’s chaotic years at the helm left the company in a precarious financial position, and in 1852, two mining companies had made offers to buy the Bruce Mine. The Commercial Bank, with which the company exclusively transacted its business, refused to advance £1,500 to pay off the balance of the winter wages, and began pressing for the settlement of its considerable debt. Fortunately, the Bank of Montreal was willing to take a risk with the company, advancing sufficient capital to save the mine from closure. A call of 5s per share was made on the shareholders in order to liquidate the debt at the Commercial Bank.

Under new management, the improvements at the mine were immediate. In October 1851, the former engineer, John Vivian, was invited back to inspect the steam engine and to make adjustments to it and the other machinery, which resulted in a considerable saving on coals. To improve throughput on the dressing floors, a new crusher with a double set of Cornish rolls powered by a large wooden waterwheel which had been purchased from the Quebec Mining Company, were installed in 1853. Additional dressing machinery was imported from Detroit. Ten new jigging machines were added to the 20 then in operation, and the amount of ore the dressing floors were able to handle was expected to be in the region of 3,000 tons per annum. In 1853, the company paid a dividend to its shareholders for the first time since its inception.

However, the smelting works, which had never performed in a satisfactory manner, had not been recommenced due to the lack of a suitable flux to smelt the refractory ores. Some of the furnace bottoms which were impregnated with ore were dug out and sold to a company in Troy, Ontario, and the rest were shipped to England. The best ores raised by the company were sent to Swansea for smelting, and the poorer ones sold in New York, but at a loss due to freight and duty costs. After 1853, the company therefore entered into an agreement to sell its ores to the Baltimore Smelting Company.

In order to recoup some capital, the company had agreed to lease a western portion of the Cuthbertson location which it wasn’t working, to Captain Sampson Vivian for 14 years on a royalty of five per cent of the dressed ore. He had begun preparatory work in the fall of 1853. Some log houses had been built and he had begun raising ore with the aid of half a dozen men. Vivian then assigned this ground to an English enterprise called the Wellington Copper Mine Company. This company, which began operations in 1853, was managed by John Taylor and Sons of London, great proponents of Cornish labour and steam engine technology. Indeed, in 1854 an engine house was being built in preparation for a steam engine, and the shafts sunk on their property reflect the strong Cornish influence: Rowe’s, Bray’s, Knight’s, Collins’s Gribble’s, Craze’s, and Glanville’s.

The Montreal Mining Company was forced to suspend the tribute system in 1853, as the Cornish miners declined to work on tribute bargains. They argued that the produce of the ground and the quality of the ore hadn’t been proven to their satisfaction, and for them to take tribute contracts entailed too much personal risk. Their wages as tutworkers might not have been as good, but a wage settlement was made within days of the end of their contracts. By contrast, tribute payment was only made after the ore was dressed, weighed, sampled and assayed, a process that could take several weeks. Many of these men had families who were financially dependent on them at Bruce Mines but also further afield, including US mining towns and back home in Cornwall. Delays in the receipt of remittances caused their families significant hardship.

In 1854, the Montreal Mining Company paid an average monthly wage of £10 for miners and engineers/fitters and £8-9 for an engine driver. A timberman was on £8-10, and the Captain of the ore dressers received £9. The reminder of the workforce was paid per day: stoker/oil man 5s; Kibble filler/lander 5s 6d; spaller, 5s; jigger, 4s 6d-5s; crusherman, 5s 6d; blacksmith, 6s 3d -9s; and carpenter, 5-8s.

Additionally, having to wait for the Montreal Mining Company to pay up meant that these men could not move on to better opportunities at mines elsewhere in the Great Lakes region. Many miners had already been enticed to the Saute where very generous wages were being paid to labourers building a canal for the locks, and in order to retain sufficient labour at the mines, the company had to begin paying higher wages. Early in 1853, the actual mining force did not exceed 45 men, when it was estimated a force of about 125 was required.

Consequently, Borron arranged for a group of mineworkers from Scotland to be brought out on a 3-year contract with the promise of a fixed high rate of wages. This proved to be a poor and premature decision, as sufficient ore ground had not been opened out to employ them all, and over the coming year they were set to work on stopes that didn’t pay. The company laid off many of these miners in March 1855 and got rid of those who would not work under the reintroduced tribute system, which this time, proved more successful.

However, 1854 was a disastrous year for mining at Bruce Mines. The Montreal Mining Company’s dressing floors were not running at full capacity as one of the Cornish rolls crushers had been stopped for vital maintenance, but the employee from the Ore Dressing Company (contracted to undertake specified dressing operations at the mine) who was sent to repair the crusher, died of cholera on his way to the mine. This company had been tasked with trying a new method of ore dressing in a timber frame building dubbed ‘The Yankee Mill’ sited to the east of the Cornish engine house. However, the mill worked for only a brief time before the contract between the Ore Dressing Company and the Montreal Mining Company broke down and ended in litigation.

Moreover, the company had ordered a steamer to convey its ores and stores, but the shipyard broke the terms of their contract by not delivering it as scheduled. This also resulted in litigation and the unnecessary expense of employing a schooner to transport the company’s ores on time to the smelting company with which they had a contract, in order to avoid a financial penalty.

After finally being delivered over 2 months late, the steamer, named the Bruce Mine, only managed to make a handful of voyages before she was lost on the night of the 24 November in a terrific storm on Lake Huron after leaving the Port of Goderich. She was heavily laden with gunpowder, a new set of crusher rolls and the majority of the winter stores required by the Montreal Mining Company. Also on board was a steam engine and other dressing machinery for the Wellington Mining Company, which severely curtailed their nascent mining operations and also had an adverse financial impact on the Montreal Mining Company, as it received royalties on the Wellington Mine’s ore sales.

To add to the Montreal Mining Company’s woes, the vessel and its cargo were found to be under-insured, and it was fortunate to be able to purchase sufficient gunpowder, steel and fuse from a company at Sault Ste. Marie to enable mining operations to continue over the winter. Over 500 people, the largest number ever at the mines, had to be supported until the opening of navigation in the spring, and the company were forced to buy replacement goods for the store at a time when the price of commodities was very high. These had to be brought in by sleigh and dog teams at considerable expense. Due to lack of feed for the horses (which worked the whims), and because there was plenty of flour, the company resorted to feeding them bread which was baked daily.

All of these problems caused a ruinous depreciation of the company’s stock. The only good news for the year was that the company erected a cupola furnace and managed to cast a few rollers and some geared wheels for the Cornish rolls crusher, to increase throughput on the dressing floor.

Over the coming years, the Wellington Mine proved to be the better prospect and in 1859 was employing 144 mineworkers, as opposed to the Bruce Mine’s 82. The mine worked the same lode as that running through the Bruce Mine, but large quantities of ore were also raised from a lode some 200 yards from the lake shore. This had been accidentally discovered after a bush fire had destroyed the surface vegetation, and it became known as the Fire Lode. In excavating a watercourse, an even wider lode was discovered. As these rich new lodes appeared to extend into the neighbouring Huron Copper Bay section, this too was leased by the company. The first dressing floors, powered by steam and built of stone, were sited in the vicinity of the Fire Lode, and a large frame mill was later built about a mile to the northwest.

From 1855, the Montreal Mining Company had resorted to allowing a few dozen miners to conduct operations on their own account. While in the short term the company saved money by not having to pay for supervision or materials, in the long term this system proved ruinous. The miners merely ‘picked the eyes out’ of the deposit, creating a maze of small workings in their quest to turn a profit. This ‘unminerly’ method of working compromised the potential of turning the mine into a payable proposition in the future, or of selling it as a going concern. Moreover, miners were leaving the Bruce Mine for the Wellington Mine, where wages were better. Ore tonnages reflected this: the Bruce Mine produced just over 456 tons, whereas the figure for Wellington was 1,400.

The smelting works, which had been shut up since Campbell’s time as Manager, were reopened in 1859 by Messrs. Fletcher and Williams of the Huron Copper Smelting Works. The beginnings were not promising, due to the poor quality of the coals used. Calamity struck in 1860 when the roof of the smelting house caught fire, rendering the company unable to fulfil its contract obligations to the Montreal Mining Company.

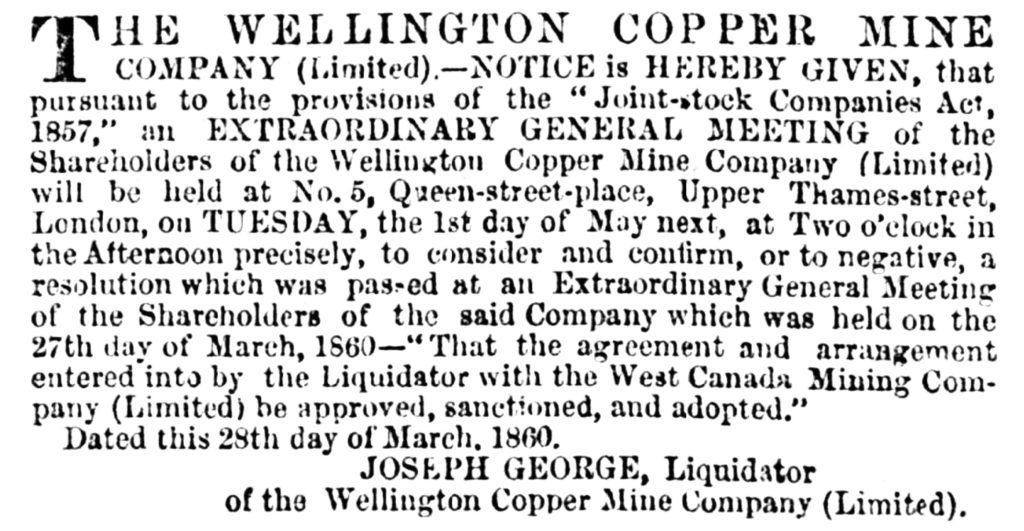

The West Canada Mining Company

In 1860, the Wellington Copper Mine Company was liquidated, and a new company, the West Canada Mining Company Ltd., was formed. Besides leasing the Wellington section from the Montreal Mining Company, it also leased the Keating location at Huron Copper Bay.

The mines were managed by an experienced and trusted Taylor mine captain, William Plummer (1819-1890). He was a Cornishman born at Mary Tavy in west Devon (his mother was a Davey from St Agnes, and his paternal grandfather was from the Parish of Kenwyn), and he ran the mines in accordance with Cornish principles of mining, ore-dressing and management. The company had constructed 92 houses of log or frame to house its workforce, and two engines, one of 36hp and another of 12hp, powered machinery and pumps. Wellington became the leading employer at Bruce Mines, with 260 employees, and supported over half of the entire mining population of Canada West (Ontario).

However, in the winter of 1864-5 when an attempt was made to impose new hours of work, a riot broke out, forcing the company to drop its plans. It regained some degree of control by dismissing 30 of the most troublesome men.

By the mid-1860s, the company had finally become profitable and the time was ripe for a major reorganisation. Sampson Vivian’s lease was due to expire, and the Montreal Mining Company was suffering from years of under investment and poor management at Bruce Mines, problems that were laid bare by declining global copper prices. Preferring to vigorously pursue some promising new ventures in the Lake Superior region, it sold the Bruce Mines to the West Canada Mining Company Ltd. in 1865.

A new concentrating mill was installed on the Wellington section to improve the dressing operations. The Cornish rolls crusher, Cornish steam engine (with a 25 ft beam) and Lancashire boilers were imported directly from England (possibly from the Sandycroft Foundry, near Chester, which was worked by Messrs. John Taylor and Sons).

In 1868, John Taylor Jr. visited Bruce Mines to examine the operation and to make recommendations for its future direction. He was concerned at the falling-off in size and richness of the lodes at depth, that the system of ore-dressing was far too expensive, and that large amounts of copper were not being recovered. The expense of mining was merely exacerbated by the high freight costs of shipping the ore to Britain for smelting, after the USA imposed a heavy tax on the importation of Canadian copper ore during the American Civil War.

Taylor recommended a return to smelting at Bruce Mines and the implementation of the Henderson ‘wet process’, which had been developed by the Tharsis Sulphur and Copper Company. In 1869-71, a state-of-the-art mill and lixiviation works measuring 150ft x 200ft and costing $200,000 were constructed a short distance west of the old mill, right in the centre of the new village of Bruce Mines.

Ten calcining furnaces were erected in which the milled ore was roasted. The roasted ore was then crushed, mixed with salt, and re-roasted. The re-roasted ore was washed and leached in hot, dilute sulphuric acid. The resulting leachate was drained into wooden vats containing scrap iron, where it underwent a process of cementation to produce a product containing around 70 per cent copper ready for smelting on-site.

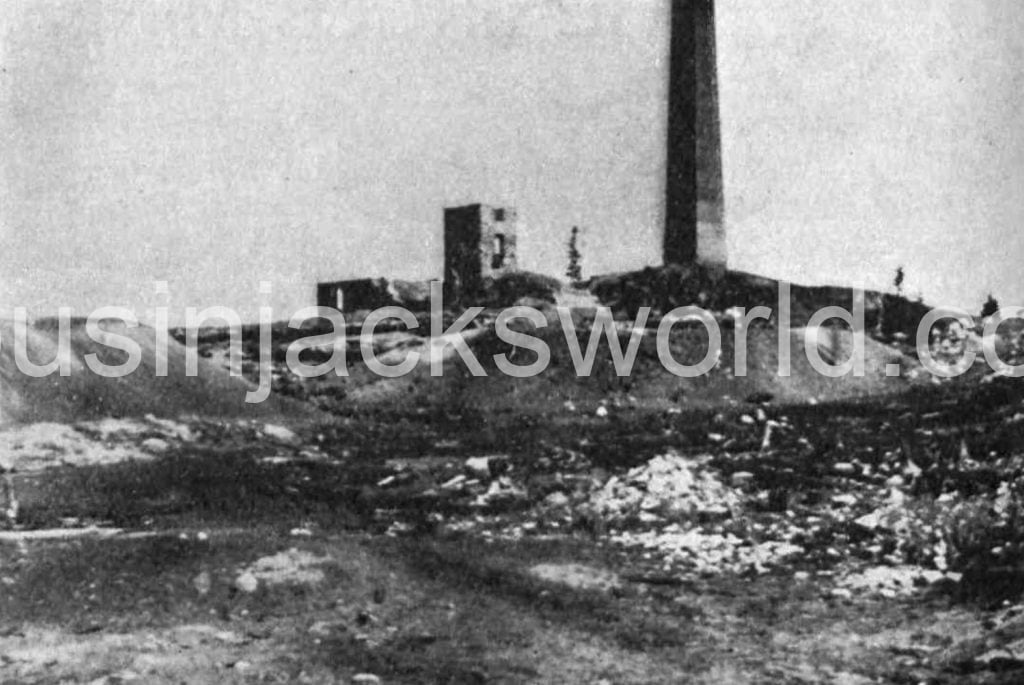

The tall brick-built chimney of the works was a landmark for miles out on Lake Huron and up the St Mary’s River. But the high cost of procuring large amounts of scrap iron, salt, and coals for roasting and smelting, commodities which were scarce in the region, meant that the new process was doomed to failure. The works operated for just two years before plummeting copper ore prices and soaring production costs resulted in their closure.

The company seemed to have attempted to recoup their losses by mining out all available ore, with calamitous consequences. A particularly rich shoot of ore, at one point reportedly 24ft wide, lay at at a depth of around 50 fathoms (just over 90m) at the junction of No. 1 and No. 2 Lodes, and was being stoped out by tributers for several months. However, the cavernous stoping caused the ground to become unstable, and fearing the worst, some of the men left the mine rather than run the risk of being buried alive. Their reservations proved accurate when on a Saturday night in March 1875, a tremendous cave-in occurred. No one was killed, but this event signalled the death knell for the West Canada Mining Company. Some small-scale tributing took place until the concern was wound up in 1876.

During its time at Bruce Mines, the Montreal Mining Company extracted copper ore valued at $3.3 million, and the Taylors raised between $6-7 million. Yet this pales into insignificance when set against the ore raised by the rich Michigan copper mines in just one year (1860), which was valued at $14 million.

The closure of Bruce Mines meant that the community rapidly dispersed. Many Cornish miners found work at the Silver Islet Mine on Lake Superior, and many more went to neighbouring Michigan. William Henry Richards of St Agnes and Thomas Carne Bice of St Columb Minor, who both migrated to Bruce Mines in their teens, moved to the Keewenaw copper mines, and Captain John Bartle migrated on to the Marquette Iron Range. Others like Thomas Youtlen moved to mining camps further afield in the US, in this case, Butte, Montana, or returned to Cornwall.

Some Cornishmen quit mining entirely to become prosperous farmers in the back country to the north of the mines which is connected by a beautiful chain of lakes. These included John Knight and John Trevillion (formerly of Camborne) who were resident near Bruce Mines; Captain J.S. Skewes and John Saunders (a native of Wadebridge) at MacDonald Township; William Harris at Day Mills; and John Crocker at Bar River. Edward Skewes, who visited some of these extremely affluent Cornish families in 1883, stated that John Knight, a miner who was from Scorrier near Redruth, was ‘living in such a style as I have not seen elsewhere for working people’.

Postscript

In 1898 a group of English capitalists formed a company called Bruce Copper Mines Ltd. They succeeded in erecting a concentrating mill, coal dock, and over a mile of railway line connecting mill, shafts and dock, before a fire laid waste to the newly erected surface plant. This setback coming hot on the heels of the outbreak of the Boer War eventually conspired to close the enterprise in 1904.

Further attempts to reopen the mines were unsuccessful until in 1915, the Mond Nickel Company purchased the Bruce Mines. The huge dumps of quartz tailings were shipped to Sudbury to use as quartz-copper flux at the company’s large Coniston smelter. The company closed the mines for good in 1921, bringing to a end over seven decades of mining. The mines were officially decommissioned in 1944, and tourism and forestry became the economic mainstays of the community.

In the early-1890s, the 30-inch cylinder steam engine imported to the Bruce Mine in 1848 from the Copperhouse Foundry was still in situ in its house close to the lake shore. The adjacent building which accommodated the Cornish rolls crusher was unroofed and part of the western wall had fallen. The remains of the long timber-frame jigging house that stood on the western side of the crusher house was also extant. The tailings dumps on the lake’s edge had been washed by wave action onto an extensive sand bar that extended about 200 yards from shore. The engine was probably scrapped in the early twentieth century, and its house and the adjacent buildings have not survived.

The same fate befell the three steam engines and associated buildings on the Wellington section. Large amounts of rock from the waste tips of the mines were taken away to ballast the track of the Canadian Pacific Railway, further eroding the industrial history and archaeology of Bruce Mines.

The ‘Jewel of the Huron’

The village of Bruce Mines was begun when the Montreal Mining Company built a number of frame houses on the lake shore to the east of the company’s mill, right below the mining operations. This helped to relieve the shortage of housing which had seen some residents having to live in tents. The early houses were unfortunately prone to periodic flooding when the level of the lake rose.

A well-paved road ran for about a quarter of a mile above the shore in front of two rows of timber frame buildings, some double fronted, which included the company’s store and offices. At the end of this road was the most imposing residence in the village belonging to the Mine Manager, sited close to the opening of the main dock. A parallel road led from the shore to the back row of houses. Some of the miners’ widows kept boarding houses to maintain their families.

Additional buildings in the village included a tavern (which was extended in 1854), a warehouse, a root house (for storing foodstuffs), a slaughterhouse and stables. The residential section was cheek by jowl with the industrial buildings, including the engine house, crushing house, jigging house, and smelting house. The powder houses stood at some distance apart to the northeast of the mine workings.

After the cholera epidemics of 1849-50 had passed, the area was considered to be very healthy, death rates were low, and a resident doctor took care of the community’s needs. A qualified teacher taught 30 children for 6d each per week, but by 1855, he had departed. There was a bowling alley and a Mechanics Institute Library with a reading room supported by a subscription of 1s 3d per person per quarter.

The community was quite a mixed one, with skilled miners from Cornwall, Scotland, and England, smelters from Wales, and labourers from Ireland, the United States, and elsewhere in Canada, some of whom were first nations people.

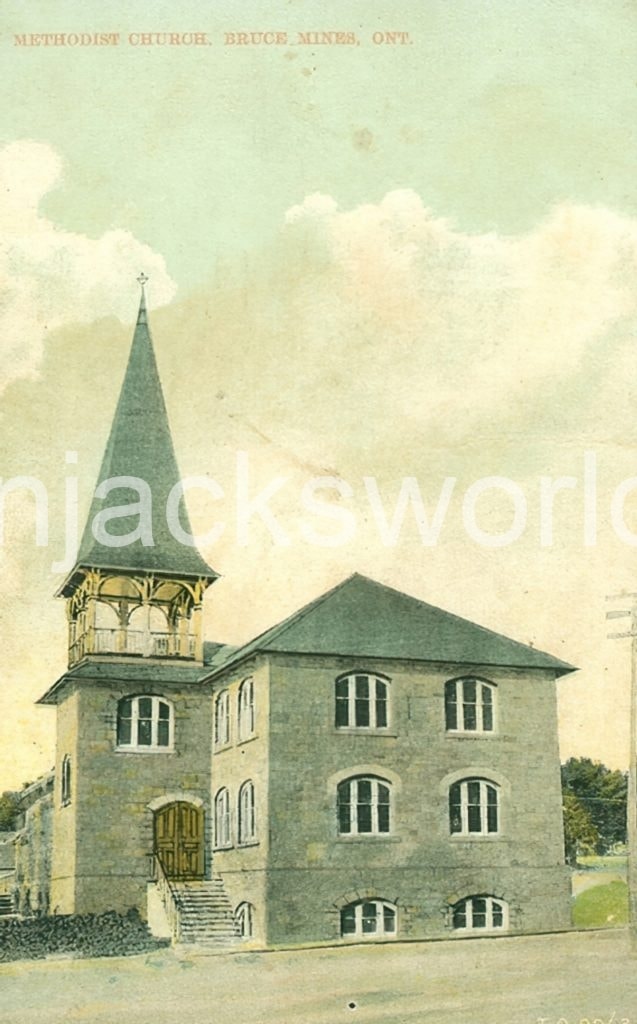

As the community had a significant Cornish population, a Wesleyan Methodist Church was started which operated out of one of the company’s houses, rent free. In 1851, the Rev. George McDougall, a missionary based in Garden River, would travel to this chapel for monthly services. Attached to it was a Sunday School which, in the immediate months after the schoolmaster had departed, was run by the Rev. Joseph Hall during the week days as a free day school for 60 pupils. He was assisted by Messrs. Pilgrim and Vivian junior, neither of whom took a salary. This school was much needed in a community which had around 200 children. A union church was subsequently built in the west of the village and was used for worship by Episcopalians, Presbyterians and Methodists. A small church was also built to serve the Roman Catholic community.

Only approved boats could use the Montreal Mining Company’s wharf and docks and, in that way, it was able to control what goods entered the village. The store was provisioned entirely by the company who stocked it during the summer months when steamers regularly called at Bruce Mines. It sold a wide variety of items, supposedly at reasonable prices. But as it was the only store permitted, it was little more than a truck shop, and unsurprisingly yielded a tidy profit to the company.

In order to break the company’s monopoly, during the summer the Marks brothers from Hilton Beach brought a barge to Bruce Bay from St. Joseph Island laden with fresh produce, meat and lumber. As it was not permitted to dock, the barge was anchored offshore, and the inhabitants visited this by boat or canoe to buy supplies at fairer prices. The company eventually relented and allowed the brothers to open a store in the village.

During the long, frigid months of winter, if people wanted specific clothing or provisions, they snowshoed to nearby St Joseph Island, and the mail was brought in twice a month from Penetanguishene by dog train. A miner from Teesside froze to death one winter just a short distance from his house when returning to Bruce Mines from a shopping trip to St Joseph Island. Indeed, the climate can be brutal at this latitude even in summer, when sudden storms on the lakes are not uncommon. One such storm in April 1855 threw down three of the smelting house chimneys, and damaged the wharves, jigging house, and some of the company’s houses.

In June of 1858 the Lake Superior Miner reported on the tragic accident to a group of Cornishmen who left the Wellington Mine en route for Saute Ste. Marie. Their small boat was overturned on Bear Lake some 16 miles from the mine by a strong gust of wind. Five Cornishmen drowned within minutes, and three were saved. Several of them were en route to their families in Dodgeville, Wisconsin, which further highlights the degree of Cornish movement between mining fields in the USA and Canada.

The fatalities were brothers, Richard and Thomas Terrell, the former a married man with a wife and two children in Dodgeville; William Angove, also with a wife and four children at Dodgeville; Robert Lord with a wife and two children at Wellington Mine, and James Johns who was single. The fortunate men, who were returning to their families at Dodgeville, were John Richards, married with a child, and John Johns who had a wife and four children.

In 1854 there were 67 dwellings belonging to the Montreal Mining Company at Bruce Mines and these were divided into 78 tenements which were rented to the mineworkers by the company. Some of the houses were quite small, measuring just 20 x 25 feet. Maintaining the log cabins cost the company a considerable amount, so in 1855 it reduced the rent on them by 20 per cent, and bound its tenants to make necessary repairs, and to pay for all materials except lime.

The settlement began to expand when the Wellington company built its own wharfs, stores, and accommodation to the west of the old village. In 1854 the Montreal Mining Company noted that there were 212 men, 94 women and 209 children under 17 at the village, and a further 56 men at the Wellington Mine, making a population of 571. By 1858, the village had grown to include 75 homes and 300 miners, and was the main settlement on the northern shore of Lake Huron.

Passing steamers often made stops at Bruce Mines, and visitors were conducted around the mine workings in an early form of mining tourism. By contrast, Sault Ste. Marie was still a mere trading post with few white settlers. However, a less than flattering report of Bruce Mines was made in a Scottish newspaper in 1858:

The village looks like starvation and the country around is desolate and barren. A church, a store, an apology for a hotel, almost 50 dwellings and a pile of buildings used for crushing ore, compose the village.

The development of the Huron Bay section resulted in an increase in population of about 10 percent and in 1859, a court was set up. The freeport system which came into operation in January 1861 proved a boon to mining operations, and the Montreal Mining Company encouraged agricultural settlement in the Bruce Mines area. This was given further impetus by the construction of a government road which stimulated farming by making it easier to export produce.

In the summer of 1862, a disastrous bush fire tore through the community, destroying most of the timber frame homes and log cabins, making a significant portion of the population homeless. The West Canada Mining Company sent a subscription of £300 to assist those who suffered most, but the families refused to accept anything and instead requested that the money be put towards a public school fund.

In 1874 it was reported that a small sum of money had been voted by the provincial government to build a lock-up at the Bruce Mines, but it was subsequently discovered that a large number of men had left for the Silver Islet Mine on Lake Superior.

This movement was a mere precursor to the exodus of people following the mine’s closure in 1876. In 1878 a correspondent to Ben Brierley’s Journal reported how he ‘went ashore at Bruce Mines and beheld a well-nigh depopulated village, which ten years ago was a town of 2,000 inhabitants’. W. Fraser Rae, who was travelling from Newfoundland to Manitoba in 1881, noted that the settlement was in decay, with many of the houses standing empty, the church falling into ruins, and the mining machinery deteriorating rapidly. The American Settler newspaper reported in July 1881 that ‘ruin and decay reign supreme… Huge piles of calcined rocks and rugged boulders appear on all sides’. This theme continued with the Gentleman’s Magazine reporting in 1892 that Bruce Mines was a place ‘whose glories have departed’:

Seen from the water it makes a pretty picture, its cottages clustered among the rocks and trees of the shore, and the Gothic roof of a tiny church lifted above the foliage. Higher appear the great heaps of rock and copper ore dug years ago, and the large building of the mining company whose employees lived in a row of houses now tumbling into hovels nearby’.

A year later it was noted that only one of the timber houses in the old village was inhabited. The rest had either collapsed, or had been pulled down for fuel, and the once well-paved road leading to the Mine Manager’s house was overgrown with weeds.

The town’s Cornish legacy is evident in place names such as Tregenza Street, Prout Street and Mitchell Street, and the Plummer Additional Township. Numerous headstones to Cornish settlers can be seen at the Bruce Mines Cemetery off Trunk Road to the east of the town.

Further Reading on Bruce Mines

G Leigh Hornick (ed), The Call Of Copper – a history of Bruce Mines and area (Bruce Mines, 1969).

Anne M Henderson and Arthur M Henderson, Bruce Mines Heritage, Bruce Mines Senior Citizen’s Friendship Club (Bruce Mines, 1984).

Dianne Newell, Technology on the Frontier: Mining in Old Ontario (Vancouver, 1986).

Visit Bruce Mines

The restored mid-nineteenth century Simpson Shaft is open for guided underground tours during the summer months. It displays a fine replica of a horse whim that was used to raise kibbles of ore from the stopes. There are a number of waymarked trails which guide visitors across the Bruce Mine site.

The Bruce Mines museum which contains lots of interesting mining artifacts, was built in 1894 as a Presbyterian Church. It was in use as a place of worship until 1917 when it united with the Methodists, whose church built in 1905 at Williams Street was big enough to accommodate both congregations.

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2023.