The Luganure Mines (Glendalough & Glendasan), Wicklow, Ireland

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2025, and may not be reproduced without permission

‘Mid Mines and a Monastery: The Cornish in the Wicklow Mountains

County Wicklow, famed for being the ‘Garden of Ireland’, was also Ireland’s most important mining county, producing a wide variety of commercial minerals, including gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron, pyrites and ochre. The two main mining areas were the Avoca Valley and the wild, mountain valleys of Glenmalure, Glendalough and Glendasan.

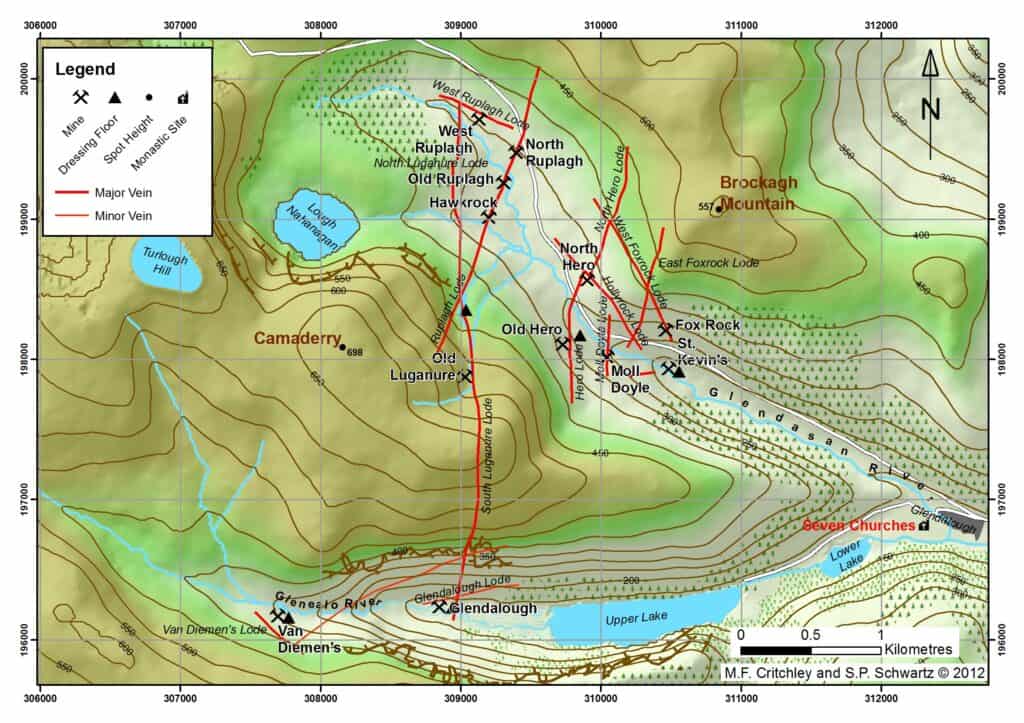

The glaciated valleys of Glendalough and Glendasan run parallel to each other and are separated by Camaderry Mountain. Mines in both valleys were worked in tandem in the nineteenth century by the Mining Company of Ireland (1824-1890), and were known as the Luganure Mines. Today they are located in the beautiful Wicklow Mountains National Park, some 40km south of Dublin, 11km from the town of Rathdrum and 21km from the Port of Wicklow.

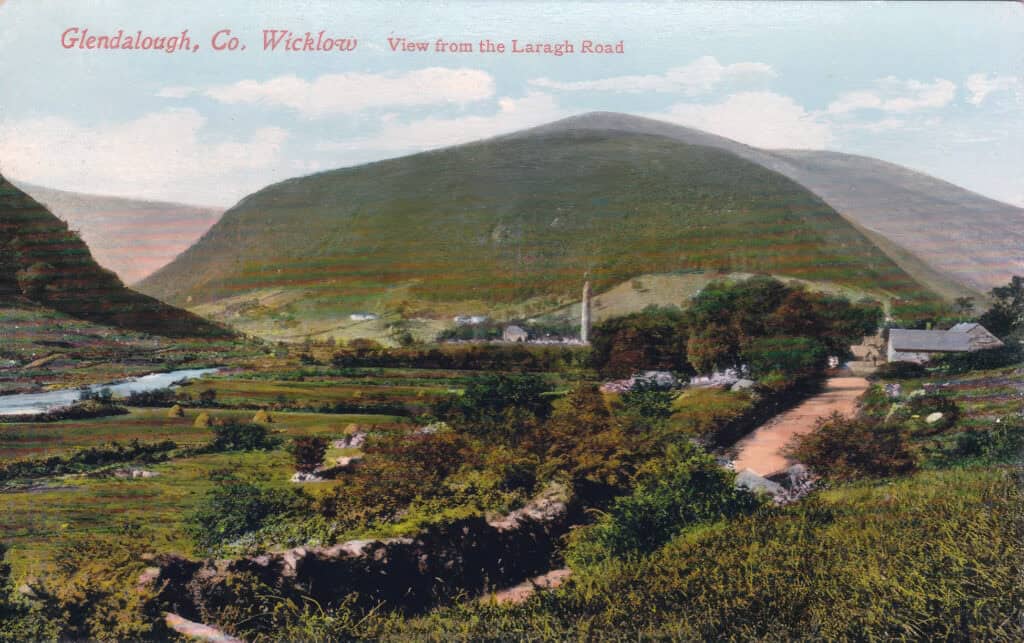

During the nineteenth century, the Luganure Mines were Ireland’s most important silver-lead mining centre, leaving behind an exceptionally well-preserved relict rural-industrial landscape. Very little has been recorded about the mines, although they lay close to the Seven Churches (Glendalough), a famous monastic site which was a tourist trap even in the Victorian period.

Indeed, amusing reports in the Wicklow News-Letter contain incidences of “nice old ladies” near the monastic site begging from respectable visitors under the pretence of selling mineral specimens from the mines, and “errant priestesses of fortune” who carried roulette wheels and preyed upon the miners by “beguiling” them out of their hard-earned wages! Yet, the industrial legacy of deep lode metal mining in the valley remains a largely hidden heritage.

Unlike Avoca which has a relict copper mining landscape dominated by engine houses that screams Cornwall, steam power was not deployed by the MCI at Luganure in contrast to many of their other operations in Ireland, so the Cornish involvement is not immediately apparent.

The area’s geomorphology meant that expensive steam machinery was unnecessary, for the mineral lodes had been exposed by the fortuitous effects of glaciation which scoured deep valleys. For example, the main lode that runs through Camaderry Mountain was accessed via cliff face adits and the water escaped freely at the mouths of various adits. The lodestuff was cheaply hauled to the surface along tramways, principally by mules, then transported to the valley floor by tramway for processing. Fewer deep shafts had to be developed, saving on pumping and winding costs too.

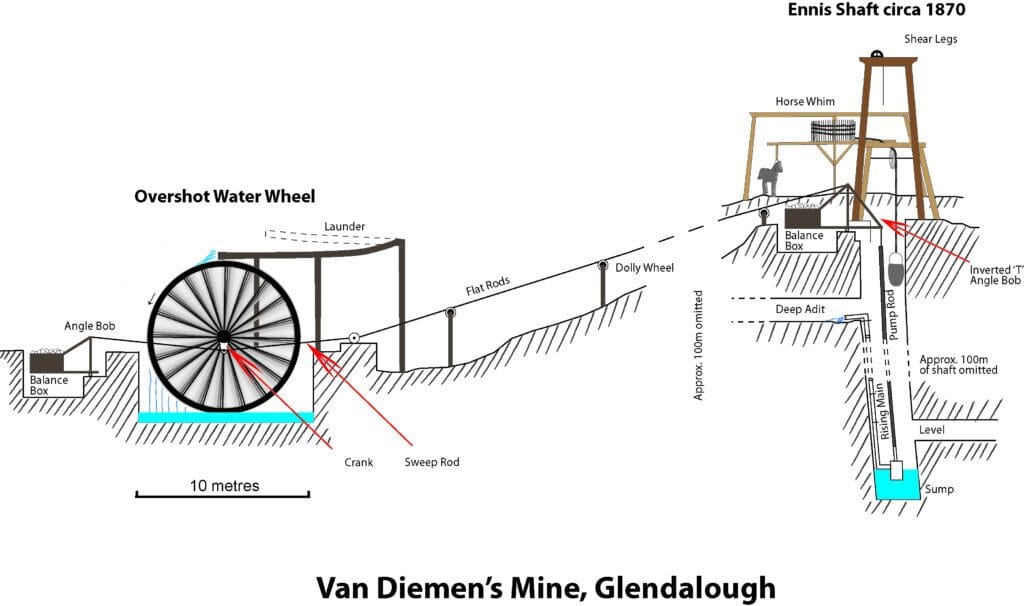

In common with many lead mines in the remote and upland areas of neighbouring Britain, extensive use was made of waterpower at the Luganure mines. The water was obtained from the glacial corrie at Lough Nahanagan, source of the Glendasan River, and the Glenealo River that flows into the Upper Lake in Glendalough.

The water was brought to where it was needed via a sophisticated network of reservoirs, weirs and leats, to power vertical waterwheels. These could transmit power either through an axle or via a ring gear to drive belts or gears for pumping and winding machinery, stamping mills and a host of other appliances.

However, water power had its limitations, such as when the water froze in the leats during the brutal Wicklow winters, or drought caused the waterwheels to stop, such as in 1844, flooding and destroying the Ruplagh Mine.

There was scarcely a lead mine in the Wicklow uplands that did not have a Cornish mining captain sometime in the nineteenth century. Yet, the significant Cornish involvement in the Luganure Mines has not been given due recognition, as much of the recorded history of the mines has focussed on the mid-twentieth century, long after Cornish involvement had ceased.

Monastic Mining, or a Load of Old ‘Ballauny’?

The Monastic City of Glendalough is one of Ireland’s great Insular Christian centres, founded by St Kevin in the 6th century AD, and the extant remains of the city with its iconic round tower attracts over a million visitors each year. Yet, the immediate area witnessed significant industry long before documented history.

The Glendalough area has the highest concentration of ballaun stones in Ireland. These enigmatic artefacts contain one or more artificial circular hollows up to 10cms deep. They might have been used to pulverise grains, nuts, or vegetable fibres, for the preparation of pigments, or even for crushing mineral ores.

Research in other parts of Ireland have determined that some ballaun stones are connected with Iron Age and early-medieval metal working sites. However, as yet, there is no conclusive date for when the Glendalough ballaun stones were in use or indeed, what they were used for.

If mineral ores were being brought to the Glendalough valley to be crushed prior to smelting, the fact that the area was densely wooded and a good source of charcoal was probably of significance. Indeed, there is archaeological evidence dating to the thirteenth or fourteenth century for both charcoal manufacture and iron-working in Glendalough which led to large scale deforestation.

Some 83 identified charcoal burning platforms, thought to date from about 1650-1730, have also been detected. Many of these date to the time the Chamney’s were importing iron ore from Britain for smelting. The need to supply charcoal to their many ironworks resulted in a ‘smash and grab’ operation at Glendalough. All available wood (including large quantities of holly, oak and birch) was felled for cordage, which laid waste to the landscape by denuding it of its deciduous tree cover.

Moreover, iron ore was not just being imported to Wicklow at this time, but also extracted locally (including quite possibly an undocumented working of a vein of iron carbonate at the head of the Glendalough valley). It seems highly unlikely that eagle-eyed mineral prospectors would have missed the tell-tale signs of lead ore mineralisation while searching for iron deposits.

In the medieval period, many monasteries in neighbouring Britain grew wealthy from exploiting galena deposits primarily for their silver content, hence the term ‘silver-lead’. Yet, so far, no documentary evidence has been found to support any monastic involvement in lead mining in County Wicklow.

However, geochemical analysis of a peat core sample taken from a rain-fed blanket bog on Camaderry Mountain has shown heightened lead and zinc levels from 1078 which does not correlate with episodes of tree cover change. This suggests an important contribution from another source other than erosion. And metal mining would seem to be the most plausible source. Future research will undoubtedly determine the provenance of the lead particles.

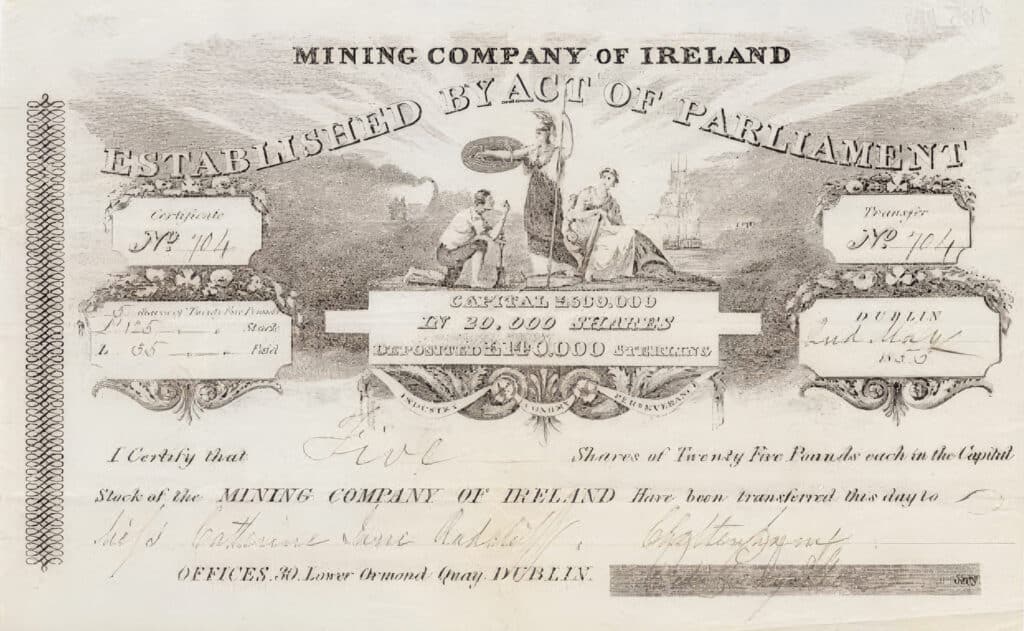

‘Industry, Economy & Perseverance’: The Mining Company of Ireland (MCI)

The Mining Company of Ireland (1824-1891) was set up as a joint stock company of £200,000 divided into 20,000 shares of £10 each (£140,000 issued) during the London stock market ‘boom’ of 1824-25. It received Royal Assent in July 1824. Unlike some of its unfortunate mining counterparts elsewhere, particularly in Latin America, the MCI survived the stock market crash of the mid-1820s and continued to operate until the final decade of the nineteenth century.

The company was set up by a group of philanthropic gentlemen, and took as its motto, ‘Industry, Economy and Perseverance’. Its list of patrons, directors and shareholders read like a roll call of the most eminent Irish landed families, politicians, industrialists and commercial traders for much of the nineteenth century.

The MCI were, on the whole, fortunate in their choice of mines, for they managed to select some of the best prospects in the island, including the Slieveardagh Collieries in County Tipperary, the Knockmahon copper mines at Waterford, and the Ballycorus lead mine near Dublin where they built a smelting works.

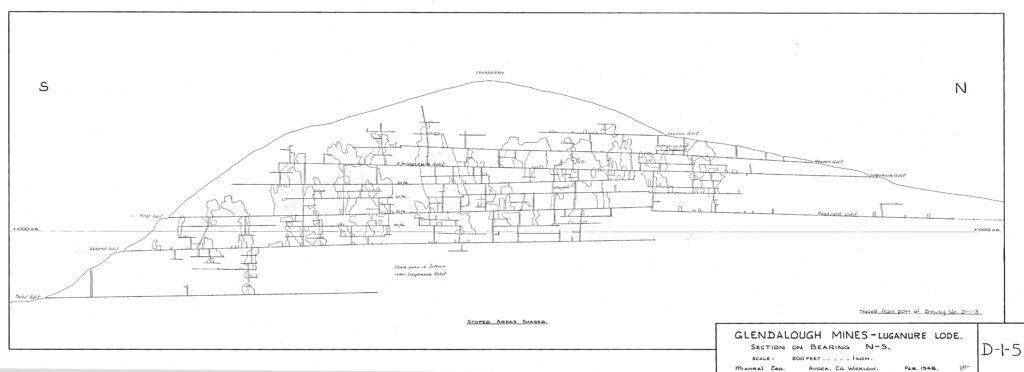

Over the course of the next six decades, the MCI would thoroughly explore their mineral sett known collectively as the Luganure Mines. This company opened numerous workings on several main lodes in Glendasan, including South Luganure, Ruplagh and West Ruplagh, East and West Fox Rock, Hollyrock, Moll Doyle, Hero and North Hero.

In the neighbouring valley of Glendalough, the South Luganure Lode was worked where it continued SW from the Glendasan valley and outcropped high up in the side of the mountain. The Glendalough Lode and those at Van Diemen’s Land were also exploited.

The MCI’s Wicklow mines became the richest and most successful lead producers in Ireland. About 80 per cent of all nineteenth century Irish lead production was accounted for by the Luganure Mines.

The Glendalough Mine Company

In 1801 a lode of lead had been (re)discovered near the Seven Churches in Glendalough, probably by geologist, Thomas Weaver of Cronebane, a shareholder and resident manager of the Associated Irish Mine Company at Avoca.

Weaver had been tasked by the British Government to survey a route through the heart of the rebellious Wicklow Mountains (which became known as the Military Road), and is credited with the discovery of the South Luganure Lode, which he commenced working in 1807.

In 1809 he formed a partnership with the Reverend James Symes of Ballyarthur and John (or Peter) LaTouche of Belview, to sink mines at ‘Glendalough and Shangeen’ (Shangan), with a total investment of £1,000. Each partner held twenty shares.

Intriguingly, on a plan dated 1814, Weaver named ‘an old trial at head of Great Ravine on Luganure Vein’ as well as an ‘old drift’ (located above the First Adit in Glendalough), strongly suggesting that these workings predate his activity in the valley and are thus eighteenth century or earlier in derivation.

In April 1825 the MCI acquired the lead mine and materials of the Glendalough Mine Company:

“Within these few days this Company has become possessed of the richest and most extensive mineral district in Ireland. The Glendalough Mine Company, consisting of a few individuals, had, for about twelve months, worked a part of the mines, situate near the Seven Churches, with considerable success; they, however, came to the resolution to dispose of the valuable possession to the Mining Company of Ireland, for a certain number of shares in that Company. Although a very considerable sum of money was offered, no consideration could induce some of the members to part with their interest, unless they had an opportunity of participating in the profits to be derived from the mines…“

Morning Chronicle, 14 April 1825

The Glendalough company agreed to dispose of their possession to the MCI as a going concern. All materials, ore on hand, and machinery, were transferred in exchange for 900 shares in the MCI. The MCI paid £4943 5s 4d for the Glendalough Royalty and £2375 for the mines and materials.

Their royalty consisted of 63 square miles and included two mines at the Seven Churches (Luganure), another at Brocka (Glendasan) and one further away at Carrigeenduff (the Lough Dan area).

The Luganure Lode, from 8-18 feet wide, had been traced for upwards of a mile at 150 fathoms in depth and was believed to extend to 900 fathoms. The Luganure Mine was 150 fathoms deep, and in full production, and the ores being raised from it were estimated to have given 80 per cent profit.

The MCI’s mines were worked on the Cornish system of tribute and tutwork and it looked to Cornwall not only for skilled labour, but also to supply steam engines, mining equipment and tools, much of which came from Harvey’s of Hayle. It was not long before the first Cornishmen were on the scene at Luganure.

Getting There

Cornish fishermen made frequent visits to Howth, Skerries and Arklow where they traded herring caught in the Irish Sea with Irish buyers, and there was a well-defined maritime trade between Cornwall and the eastern ports of Ireland, including Arklow, Wicklow and Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire).

The MCI smelted much of its own ore at its works at Ballycorus to the south of Dublin from 1828, so it did not need to send its ore to Britain for smelting. But mineral ores from other mines were exported from Ireland’s eastern ports to Liverpool or Swansea. Passages could be readily obtained aboard vessels plying the Irish sea from these ports, and also from Cornwall (particularly Hayle or Falmouth).

Early Cornish Involvement

The Luganure mine rapidly produced 120 tons of ore. This was removed to the mills, then smelted (probably at Ringsend, Dublin) and the first lead products were sold. Within no time at all, the mine had realised, after expenditure, over 20 per cent of the purchase money.

However, it was described as confined and almost inaccessible when assigned to the company. In August 1825, Mr Dodd, the company’s Mine Inspector, gave orders to open, enlarge, and timber an old level. Six men were so employed, in three divisions of two men each, relieving each other at intervals of eight hours. This was a highly skilled job and we learn that two ‘Englishmen’ having been a few yards in advance of the new timber were entombed by a falling in of part of the level’s roof one afternoon.

Three hours after the incident, the next shift discovered the collapse and raised the alarm. Inspector Dodd, the mine Agent, and a great concourse of miners and labourers rushed to the scene of the accident. Several Irish miners from the neighbouring mine of Glenmalure hastened over the mountains. All worked throughout the night and the following day, when, about nine o’clock in the evening, the two men were released without injury and none the worse for being confined for 33 hours without food. These timbermen were undoubtedly Cornish.

Indeed, the company had appointed Captain John Davey (c.1785-1847) of Gwinear, Cornwall, as its Managing Agent. This position meant he had control of not just Luganure, but other company mines such as Knockmahon in Waterford, as did his successors. Several veins had been discovered in the extensive royalty of Glendalough and considerable ore had been raised at rates not exceeding £1 per ton of dressed ore from a new mine named Hero in Glendasan.

Under Davey’s management, the mines were developed in earnest. The Luganure 20 fathom level had been opened and extended, railways were laid from the forebreast to the dressing floors; the 48 fathom level had been driven a considerable distance and was within 50 fathoms from ore bearing ground. The company continued to push the Deep Level (Luganure Adit) towards ore-bearing ground.

Due to the area’s remoteness, additional buildings for accommodation of workmen and agents (especially the ‘English’ employees) were constructed, and more machinery was erected for unwatering and working the Hero Mine (probably a horse whim and pitwork). In order to improve transportation, a road from the mine to the Seven Churches was opened and repaired to admit of cars conveying ore. Prior to this, ore and materials had been carried by men a distance of over a mile.

In addition, a new road from the Seven Churches to Hollywood through Glendasan and the Wicklow Gap that passed close by the mines was being planned. This vital arterial road would have been of great benefit to the mines’ future prosperity. The Commissioners for Public Works advanced to the Treasurer of the County a considerable sum towards completing the works.

Early work was focussed mainly on the Hero Mine and South Luganure in Glendasan. However, by the late-1820s, a series of setbacks stymied development. Work was hampered for a time due to foul air on the Luganure Lode, which was ameliorated by use of a water blast.

A delay in the road building project (contiguous to the mines) was seen as injurious to the company. At the Luganure Mine the workings were retarded and it was thought they would probably remain so until the new road that had reached Hero was extended to the intended point of junction with that from Luganure. The Board of Directors applied to the Grand Jury to gain authorisation to build the road from Seven Churches to Hero for the sum presented by the Commissioner for Public Works to the County Treasurer. It was hoped to have it operational by the 1st of September 1829.

The falling price of lead almost put paid to the mining operations. Some of the works were suspended and tribute rates were reduced to save money. The returns from the Company’s mines at Knockmahon and Luganure were seen as unsatisfactory. Captain John Davey was accused, perhaps unfairly, of ‘picking the eyes out of the mines’ and returned to Gwinear in Cornwall following a personal tragedy when his son, Martin Harvey Davey (born in 1813 at Laity, Phillack, Cornwall), died at Stradbally in 1832.

Gwennap-born John Petherick junior was installed to try and turn fortunes around. He was formerly a Captain at Fowey Consols Mine and had recently reported on the Alten Mine in Norway. His brother Thomas, employed at Fowey Consols, was the inventor of a mechanised hydraulic jig which was used by the MCI, including most probably, at the Luganure Mines. The company also employed his brother William as a Mine Captain.

Petherick had inspected all the company’s metallic mines and had given a favourable report. Expenditure on the Glendalough and Luganure mines were exceeding profit, but he recommended that the suspended works be resumed. A new 31-year lease was granted to the company by his Grace, the Archbishop of Dublin, who commuted his one tenth of the produce to a rental of £92 6s 2d per annum – a sum more palatable to the company.

It was not until the mid-1830s that a slight recovery in lead prices resulted in the opening of Ruplagh Mine and improvements to the main dressing floors at the head of the Glendasan Valley. Even given the continued depressed price of lead, due to their sagacious operations the MCI managed to turn a profit in the late 1830s.

However, establishing an industrial enterprise in a remote and mountainous region with no immediate tradition of mineworking was not easy. It was very difficult, for example, to get sufficient labour for the main dressing floors.

Females were certainly employed at the surface of numerous Irish mines but Cornishman, Captain Richards, grumbled to Frederick Roper, who interviewed him in 1841 as part of the Children’s Employment Commission, that he had tried ‘all in his power to persuade the poor people in the neighbourhood of Luganure to let the children, boys and girls, come to work at dressing the ore.’

He had even offered to advance them money to purchase suitable clothing to enable them to begin work, without effect. ‘A few boys were sent in the summer, but no girls… the girls would not go, and will not work.’ Richards stated, ‘they are too proud’ which he attributed to laziness ‘and this too although they have but a bare subsistence’.

It appears, at least in the early 1840s, that mainly adult males were employed on the Luganure dressing floors ‘on contract work’ and Richards states that they were constantly changing hands, highlighting the problems of promoting an industrial enterprise in what was, a largely agrarian area and among a peasantry not accustomed to this type of labour.

These floors were modernised in 1850-1 with a set of stamps (probably imported from Cornwall). These were erected to pulverise the accumulated halvans (poorer ores) and proved to be a great success. The bed of this stamps battery can still be seen on the dressing floors.

The company correspondence is fairly silent during the famine years where the Luganure mines are concerned, but the mining areas of Wicklow were far less hard hit than many other parts of the county, and the country at large. Miners remained a largely homogenous group divorced from the agricultural world. According to evidence given at the 1844 Devon Commission, many of them were used to migrating back and forth between Ireland and Britain, highlighting the mobile nature of the mining population.

But the company would not have been insensitive to the needs of the poorest. In Knockmahon John Petherick paid £10 towards famine relief from his own wages, and in 1846 Richard Purdy (the company secretary) left Dublin to obtain emergency help for the workforce at the Waterford Mines.

Captain Clemes and the Glory Years

The mines attained their zenith in the 1850s and 60s when the price of lead was high. A new mine at Glendalough was opened in 1853. However, initial progress was hampered by the vexatious harassing of local tenants who attempted to thwart any development.

The company had been unable to erect crushing machines for fear of damage, was refused permission to create roads and miners’ accommodation, and had resorted to conveying the ore by boat across the upper lake at Glendalough, presumably to the main dressing floors in neighbouring Glendasan. This had prompted the company to purchase the lands held by these tenants for £4,000. Interestingly, the greater portion of the ruins of Glendalough Monastery then came into the company’s possession, and they mooted plans for their restoration, possibly to placate the local population.

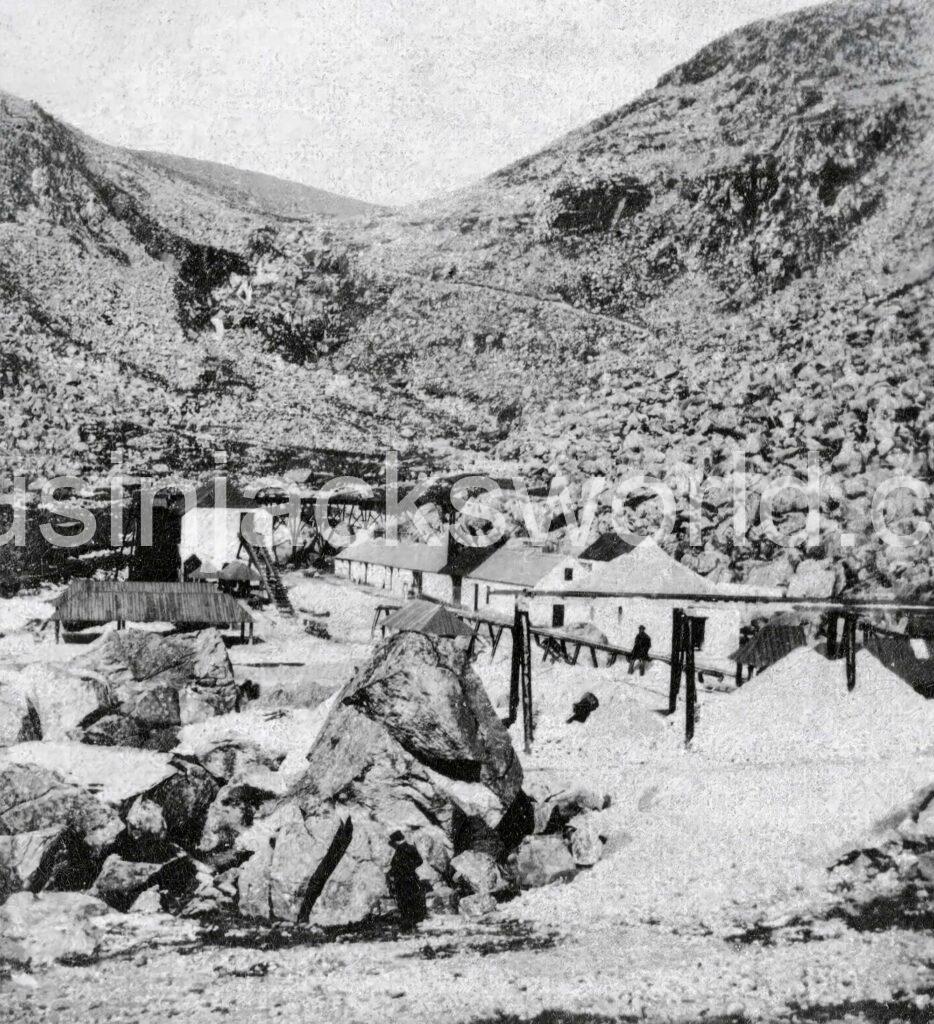

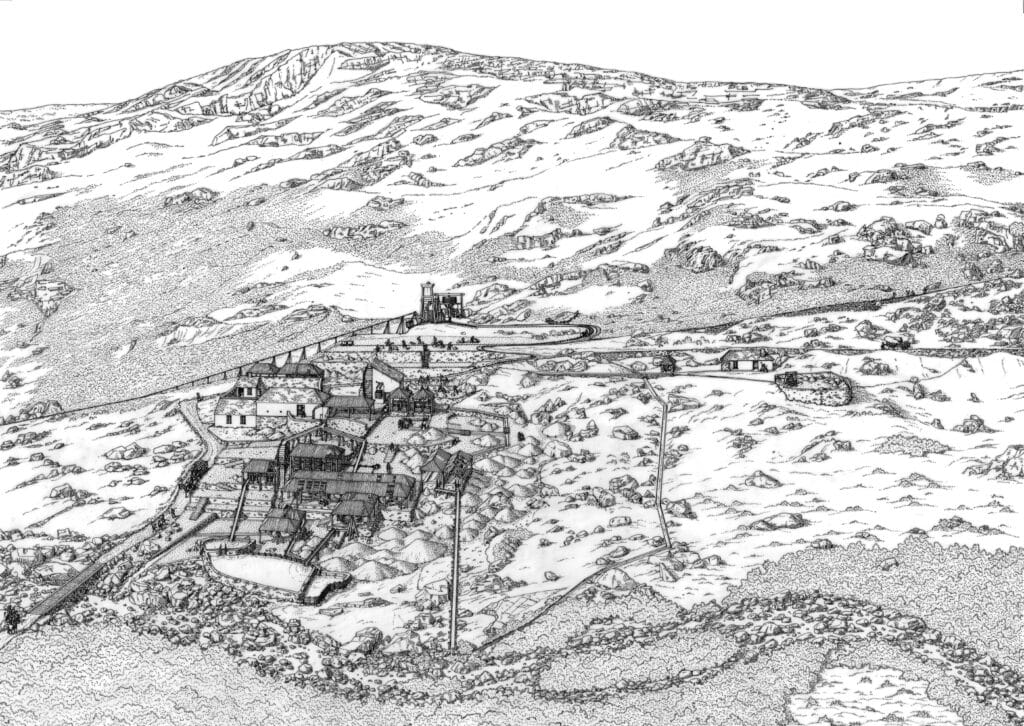

The purchase of the land cleared the way to develop new dressing floors above the Upper Lake in Glendalough which cost over £1,000. Work commenced in 1855. The works were situated immediately below the beginning of the Glenealo ravine amid numerous large glacial boulders, and were surrounded on all sides but the east “by frowning precipices, 1000 feet high.” These dressing floors are now erroneously named the ‘Miners’ Village’. The buildings were for industrial, not residential use.

These new dressing floors were described by Cornishman, William Brenton Symons, in 1866:

“They are thus so secluded and hid from observation that they are quite invisible until you actually enter them; once there, you will find them compact and well laid out. There is a crusher worked by a water wheel; there are also stamps, and several patent jiggers. The most interesting machine on the floors is a new round buddle, similar to some used in Wales, which itself rotates, and separates the ore into three parts, each part falling into a separate receiver. This avoids the usual labour required to empty the buddle, as heretofore done and enables the machine to work constantly. There are 70 hands employed on the floors and 250 in the ends and stopes.”

In 1856 the workings in Glendalough and Glendasan were connected by an adit driven 2.5 km through the heart of Camaderry mountain. This was the brainchild of Cornishman, Captain John Clemes, whose 1854 report on the mines pushed for their extensive development, including the setting up of the new dressing floors. His father James (1797-1871), a native of St Austell, was the Agent at the company’s Knockmahon Mines in County Waterford, where his son had first cut in teeth in the mining industry.

Captain Clemes had completed this undertaking ‘of magnitude and difficulty’ by connecting the First Adit high in the glaciated cliff face of Glendalough, with Richards’ Adit (later known as Hawkrock Adit) which had been driven from the neighbouring valley of Glendasan, the portal of which was over 2.5 kilometres away.

The majority of the ore stoped in the workings within Camaderry Mountain could then be sent along First Adit in Glendalough and/or dropped by chutes into the Second Adit level, to be trammed from either level by mule and transported down to the dressing floor via an inclined tramway. This was cheaper and more convenient than having to transport the lodestuff by cart to the Hero dressing floor from either Richards’ or Luganure Adits.

By 1861 the main gallery was some 300 feet in an almost perpendicular line above the works, connected with the gallery by a gravity tramway “up and down which rush, with a velocity terrible to look at, the wagons containing the ores, the ascending train ensuring the empty one to ascend.”

In August 1861, the Luganure mines were visited by members of the Social Science Association, who were ably conducted through the works by Captain Clemes, who kindly gifted some of the members several excellent specimens of ore from his personal collection.

Glendalough was popular with invalids who came to the mountains for their health, and many stayed at Jordan’s Hotel which had a nice pleasure gardens. But Clemes’ handiwork at the head of the valley did prove aesthetically pleasing to a Victorian walker who, descending the dale-head past the mines in 1879, thought that the works “rather spoiled it.” Symons was kinder in his description:

“[it is] an interesting and novel sight to stand at the bottom of the ravine or barranco, and, on looking up, to see the wagons appear at the mouth of the levels, which come out in the face of the cliff… It is curious to watch the wagons going up and down the nearly perpendicular and seemingly aerial tramway, and observe them deposit their burdens and immediately rush up the rails again. This tramway goes up the cliff to the height of 600 feet, bringing down the whole product of the mines.“

B. Symons, 1866

With production soaring, additional housing was required to accommodate the workforce attracted to the mines. Between 1858-60, cottages built to the specifications contained within the Cottier Act were constructed. The company planned to add 10-12 cottages a year, as they believed that by promoting the comfort of the people working for them, they did a great deal to improve the interest of the company. This paternalistic approach was reported on favourably by the Wicklow-News Letter in July 1864:

“The Mining Company have also borne a helping hand in the task of improvement, for the hillside is dotted with neat cottages instead of the old tumble-down cabins formerly there, and hardly distinguishable in the distance from the broom heather around them.”

Clemes’s development of the mines helped to offset the slump in lead ore prices during the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, and he was also more successful than Captain Richards had been in getting female labour (aged 14-20) for the dressing floors, even though one shareholder voiced his concern about the suitability of this work for females. Their labour was essential as productivity soared after the connection had been made between the two glens.

We know that there were local women working there, because on the 5th of May 1873, 15-year-old ore dresser Catherine Hennessey caught her hair in a revolving shaft and was so injured that she died on the 13th of May at the Rathdrum infirmary.

Mining was undoubtedly a dangerous occupation, both above and below ground, and the company operated a sick fund: 1s per month was deducted from the workers’ wages and applied to the afflicted in case of serious illness or injury.

For some time, Clemes and the company had been subjected to litigation by a fractious tenant occupying land on Camaderry Mountain contiguous to theirs. In order to prevent further vexation, in 1861 they purchased his 1/6th of the mountain for £1,000, which they then had to themselves.

However, local opposition to the mining did not cease there. In echoes of previous problems the company had suffered due to legal proceedings against them for alleged lead poisoning of cattle, in 1863 there was mention made to fish being poisoned in Glendalough.

This perhaps prompted the company to create a square reservoir below the new works to capture the fine material in suspension that had escaped the dressing floors and thus prevent lead from escaping into the lough.

This purchase of the remaining land on Camaderry Mountain led to the planting of larch and fir, which was commenced at Glendalough in 1863. About 180 acres were quickly afforested, and it was estimated that there were around 70,000 trees and over 200 acres more to plant, so a nursery was established in the valley to effect this. The cost of afforestation was about £8 per acre including fences, but the company considered the expenditure to be worth it, as free wood would be had for future stullwork (timbering) in the mines and they also planned commercial sales. Over a million trees were planted by the MCI and this forest may still be seen in Glendalough.

One of Captain Clemes last duties was overseeing the erection of some new buildings in 1865 on the company’s Glendalough Estate, in consequence of giving up a portion of the property. Over £170 was spent building new cottages for the miners and steward.

In October 1865 he was enticed away from the MCI by a group of British mining adventurers who offered him big money to go to Sonora, Mexico, with Captain John Petherick. He accepted their offer. The MCI acknowledged that he was one of their best officers, and duly presented him with an address and a testimonial consisting of a valuable gold watch and silver goblet on his retirement from the management of the Luganure Mines after a service of 19 years with the company. By 1872, Petherick was trying to promote a mining company in Wyoming, to work a lode aptly named the ‘Irishman’.

To replace Clemes, the MCI brought Nancekuke-born Captain Charles Thomas Crase (1823-1871) over from Halsetown, St Ives, in Cornwall. He was one of a well-known Camborne-Illogan mining dynasty, and was recommended to the company by Captain Charley Thomas, who had been on the management of Cooks Kitchen Mine. His brother, James Crase, was manager at the Knockmahon Mines.

Captain Crase goes to Van Diemen’s Land

Captain Crase took over a mining enterprise in good order, and he instituted several trials seeking new prospects to develop the mines further. Orders flowed into Harvey’s of Hayle for waterwheels, gearing, windbores, pumps, tram wheels and a variety of tools, which had to be marked ‘MCI-D’ and delivered at Dublin (or Wicklow).

Luganure and Glendalough were by then old mines, and their working had necessarily to be confined to side lodes and unwrought ground; but Crase was confident that large quantities of ore was yet to be found in them.

Indeed, Luganure had witnessed some falling off in its produce, but it was not the only string to the company’s bow. Three new places were at work. Ruplagh, which had been flooded and abandoned during a time when company’s fortunes were low, had received new interest. Original drawings made of the mine were inspected and information was obtained from some of the ‘old men’ who had been employed in it. Consequently, it was thought worthwhile to reopen it. At Foxrock, a mile and a half away, another valuable mine was opened and began raising 50 tons of ore a month.

But the most stunning prospect was the amusingly named Van Diemen’s Land Mine, which was opened in 1867-8. It must have felt like being dispatched to the Antipodean penal colony, for the new mine lay in remote windswept bogland high above the Glenealo ravine, and a zig-zag road had to be constructed to reach it.

Things did not get off to the best start, as Ennis Shaft (named after a distinguished member of the board, Sir John Ennis), fell in. Works were impeded and it had to be re-timbered all the way down, at a cost of £600. Crase pushed on undeterred, buoyed by the fact that the company’s mines were reported to have had plenty of reserves (3,600 tons of ore) and could thus absorb the unexpected cost.

Van Diemen’s Land had been working for some 18 months and a large quantity of ore had been discovered and was within the miners’ sight. Captain Crase had inspected it with renowned geologist, metallurgist and mining engineer, John Arthur Phillips F.R.S., F.G.S., (1822-1887), a native of Polgooth, Cornwall, and another Cornish captain named Bryant.

Captain Bryant was impressed by what he saw, believing Van Diemen’s to be rarely equalled for a young mine:

“I have no hesitation in saying that it will, in my opinion, make a good, if not a better, mine than any previously worked this district.”

However, he cautioned that it was important not to overlook the fact that there must be time to sink a shaft and open levels, and to prepare dressing floors and develop transportation networks, before large returns could be made.

The biggest impediment to progress was the fact that the mine was very high and inaccessible, and a long distance from the dressing floors, and the steep metalled zig-zag road took a long time to reach it and was awkward for heavily laden ore carts to traverse. The Board therefore decided on constructing a tramway for their trucks to run down the surface of the mountain, the full truck bringing the empty truck up, as was the case with the Luganure workings.

This was going to cost a pretty penny, and full consideration was given to the expenditure. Captain Crase calculated the saving in bringing down the ore in sight, if they never discovered another pound, would cover the expense of constructing the tramway, which he thought would cost £1,400 or £1,500.

Phillips believed the sum would be rather more than that. The Board assented to the proposal and in 1870 the tramway to Van Diemen’s Land was completed at a cost of £2,300. The lodestuff was washed and roughly dressed up at the mine first, where a small dressing floor and bouse team (ore store), as well as a cottage can be seen. It was then conveyed down the tramway to the main dressing floors at 2d per ton, instead of several shillings by horse and cart.

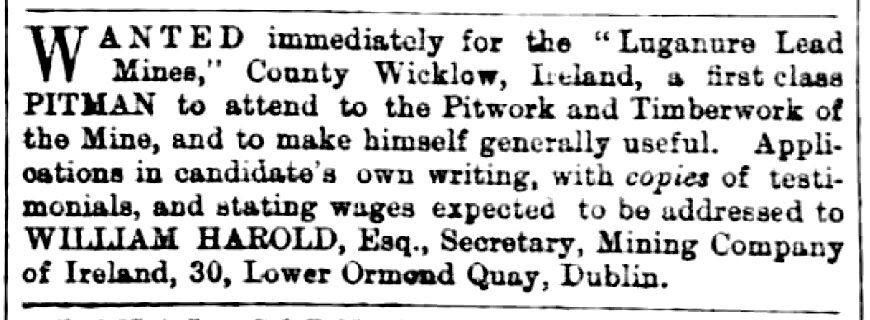

The mine was then rapidly developed and an advertisement in Cornish newspaper, the Royal Cornwall Gazette, is undoubtedly in relation to putting in the pitwork (pumps) for the new mine:

The success of the mines swelled the local population, but the fear of Fenianism meant that some newcomers were viewed with suspicion. In January 1867, six passengers who had arrived at Dublin on the Iron Duke steamer from Liverpool were arrested on suspicion of being Fenians. One was carrying an American passport. When questioned, the men stated that they were miners and natives of the Seven Churches district who had been working in Lancashire, but had returned home in the hope of finding better employment at the Luganure mines.

However, the mines’ success had also drawn the attention of the Rathdrum Union which wished to revaluate the rates that had been set for Luganure property in 1868. It appeared that the mine was formerly valued at £2,500, but had been reduced to the sum of £1,500 by the Commissioner of Valuation upon statistics furnished by the MCI.

The Guardians objected on the ground that the facts did not warrant reduction at all, or least not such great a reduction, especially since the property of the mining company was increasing in value. The value of the ore raised in the year amounted to £18,000, the working expenses were £13,000, which left a profit of £5,000 a year.

The plant of the company used in working the mine was estimated £20,000, and the floating capital necessary to work it £3,000 to £5,000. In 1854, the mine was rated at £1,000, a valuation against which the company unsuccessfully appealed. In 1859 the rating was raised to £2,500 at which it had continued up to the present year, when, on the representations of the company, it was reduced to £1,500.

Several witnesses were examined, including Mr. William Harold, Assistant-Secretary to the mining company, Mr. Daniel Johnson, and Mr. Charles Crase, Captain of the Luganure Mine.

The court had very little evidence to guide them upon the matter and after some discussion, in which several Acts of Parliament were reviewed, it was ruled by the Chairman, and conceded by the counsel for all parties, that the criterion under which the rating value of a mine must be determined, was the rent likely to be obtained from a solvent and prudent tenant.

The Chairman then announced the Court’s decision: the mine was to be rated at the sum for which it could be reasonably expected to be let. If either party thought they could produce further evidence, he would gladly let the case stand over, but being pressed for a decision he reminded the court to remember that the onus of proof lay on the appellants—the Guardians of the Union. He was inclined to think that rent of £1,500 was too low and that of £2,500 was plainly too high.

No material had been placed before them in evidence to enable them to fix on any sum above £1,500, and they had therefore no alternative but to accept that the valuation must be assumed as correct until the contrary was shown. The appeal was therefore dismissed and the rating affirmed.

The Rathdrum Union was unhappy with the verdict and challenged it, stating that an unfair proportion of the support of the poor of the Brockagh electoral division would be thrown the other rateable property of that division, as well as on the resources of the union at large.

At their invitation in the autumn of 1869, Cornish Captains, William Bishop and John Dower from Avoca, were ordered to inspect the Luganure mines which took them nine days. They valued the mine plant at £7,000. The matter was held in abeyance and we hear no more of it in the company records or the press, suggesting that the company prevailed over the Union.

‘The Brightest Feather in the Company’s Cap’: The Mines’ Last Hurrah

The 1870s opened with a falling off in the productiveness of all of the mines in the district. Van Diemen’s Land proved not to be as rich as hoped and the mines were registering a loss of over £1,000 per annum. The amount of ore raised declined for another reason too: the emigration of many of the mines’ best tributers. The majority of these migrated to the burgeoning iron mines of North West England, especially Cleator Moor, and could not easily be replaced.

In February of 1871, Captain Crase died aged just 39 of diphtheria at Bunmahon. He was interred in the Church of Ireland graveyard at Knockmahon where his memorial headstone may still be seen. Things were looking so gloomy that the MCI considered abandoning the Luganure District altogether.

Crase’s replacement, Cornishman, Captain James Mitchell, who had enormous experience of mining in Chile and other parts of the world, saved the day. Under his management, Luganure was reported to have been looking better and the raisings had increased.

Moreover, a new mine on the Hero Lode had been discovered in virgin ground, close to where the company had been working some 20-25 years before. The Luganure mines again became the most profitable and best part of the company’s business, and were described as ‘the brightest feather in the company’s cap.’ Captain Mitchell was even told not to raise above a certain tonnage of lead!

Mitchell was a moderniser and completely overhauled the dressing operations. He took advantage of the modifications that had been made at the Glendasan dressing floors in 1869, which cost over £1,744 and saw the installation of new buddles fed by a new watercourse, which was cut following an alteration of the dam at Lough Nahanagan. This also ensured a continuous supply of water-power to the machinery in summer time.

In 1874 he invented a new mode of dressing that increased the quantity of ore which was the most complete and successful the directors had ever seen. The main dressing floors were entirely remodelled and new and improved dressing machinery was erected at a moderate cost. Two or three boys now did what it took nine men to do before and much less space was required. These were probably self-acting buddles.

In 1877, expenditure on making a new road through the plantations and repair to watercourses and compensation for surface damage by mine operations since 1852 amounted to over £440. In addition, damage had been caused by the overflow of Lake Nahanagan which suppled the the water power to the Glendasan machinery. Consequently, a siphon was erected at a comparatively small cost, to prevent the recurrence of flooding and consequent damage.

New experiments were being tried in the mines which were performing well, given the depressed condition of trade, as lead ore had decreased in value £25 per ton in two years. However, in 1878, low lead prices coincided with a reduction on the amount of ores raised. To mitigate against this, over £212 was expended in erecting a new crusher house, a jigger and machinery for the more economical dressing of the halvans ore at Glendasan.

In 1879, the dressing floors and other works were in an improved and satisfactory state, yet no new discoveries had been made and the company had had encroached on their lead ore reserves to meet the demands of the Ballycorus smelter. A total loss was recorded at the Luganure Mines, and prospecting for new ore yielded nothing of value. The only bright prospect was that the price of lead had begun to increase.

In 1880, over £336 was spent on installing a waterwheel and other machinery on the North Lugaure Lode, and further expenditure came in the form of £1,200, paid to the Commissioners of the Irish Church Temporalities. This was for the mining royalties of the manors of Glendalough and Shangan which had hitherto been held by the company on a terminable lease at a yearly rental of £96 18s 6d.

About 12.5 years of the lease remained still unexpired when the lessors’ interest in the lease and the reversion of the royalties at the termination of it were offered for sale. This was brought by the MCI to prevent it falling into the hands of strangers. The company obviously still had confidence in the Luganure Mines. However, a shareholder ominously pointed out that in the last six and a half years, they had made a loss of £6,351.

Indeed, by 1881, the financial situation had worsened with another loss of over £3,000. The Board took immediate action to effect a material reduction in the establishment.

The poor outlook of the mines had prompted the directors to authorise an inspection of the workings by Captain William Kitto, the mining engineer of the Foxdale lead mines in the Isle of Man. He was a Cornishman, born at Rose, Perranzabuloe, in 1828.

Consequently, Cornishman Captain Bayley (Bailey) was invited to the Foxdale mines to inspect the most improved methods of working and came back with various practical suggestions for improvements which were carried out at Luganure. A remarkable improvement in prospects were noted, with many of the former poor pitches and branches becoming very valuable.

However, this was something of a false dawn. The death of the Luganure Mines was a drawn out affair. They made a loss of over £2,500 the the first half of 1883 due to a drop in the price of lead ore and the only prospect of success was economy of working and charges in management, resulting in lay-offs. By the end of 1883, there were hints that the company might withdraw from Luganure.

By 1884 the severe depression in the lead ore market was causing mines in Wales to shut up. Consequently, no large expenditure of capital was entertained. As if to compound matters, the company had to deal with the non payment of rent by a small tenant who had been let the shooting and grazing rights on the Glendalough Estate. He had got himself into business difficulties and had been unable to meet his rent. The company was forced to order an eviction.

In 1887, it was noted that the company was doing well at sheep grazing and selling rabbits on Glendalough Estate. But this, along with the commercial forestry, was hardly likely to compensate for falling lead ore sales.

In 1888, Captain James Hore, formerly of the Knockmahon mines, surveyed the Luganure mines and completed cross sections and plans that looked suspiciously like abandonment plans.

Luganure was once again turning a profit in 1889, but rumours were abroad that some of the shareholders had ‘ventilated’ their anxiety about the MCI’s future, and had been talking about winding it up. By now, the writing was on the wall, and in mid-1889, the inevitable occurred.

There was no prospect of successfully continuing lead mining at the Luganure property, as the rich deposits had been exhausted and the cheapness of supply of foreign producers rendered it impossible to raise lead on the property at a profit. There were plans to close the Ballycorus smelting works. The Knockmahon Mines, long a mainstay of the company, had suffered greatly from decreasing tonnages and the low price of copper ore from the mid-1870s.

In the summer of 1889 it was agreed to liquidate the company. The Glendalough Estate was valuable independent of its mineral produce, and in the summer of 1890 an advertisement for the sale of the Estate and Mines of Luganure was published. It marked the end of an era, for the MCI had worked the mines since 1824, had provided employment and sustenance to many hundreds of families, and its royalties extended over 30,000 acres. The sale included waterwheels, the siphon, the dressing floors and dressing machinery, and all the appliances for carrying on mining.

The auction was to be held by Messrs Battersby & Co. on 29th July 1890. It was planned to commence bidding at £5,000 but someone offered one tenth of that price which was instantly doubled. The mines eventually went to Mr Wynne of Ballybrophy for £3,450. His intention was to work the mines and continue the industry.

The ‘Wynner’ Takes it All

The Wynnes stated their intention to continue mining, but as their plans were continually stymied by a lack of finance, the workings were on a far smaller scale than during the MCI era. In fact, far from continuing serious mining, they ransacked the mines in their quest to claw back some of the purchase money. They sold off anything that was of mercantile value, including horse whims, pitwork, tram rails, waggons and waterwheels.

Work initially focussed on the White Rocks (Third) Adit in Glendalough and also the Foxrock Lode in the neighbouring valley of Glendasan, but operations soon foundered due to lack of capital. In 1900, in an attempt to raise capital to further explore and develop the mines, they set up the Wicklow Mining Company Ltd., but their ambitious plans were shelved due to a lack of capital investment.

In 1913, a small plant had been set up at White Rock (Glendalough) to crush and retreat the MCI waste dumps for their lead and zinc content. In 1917, the Glendalough Mines Ltd., was set up to develop the mines as well as to take over working this small treatment plant.

In August 1917, at the height of WW1, the Ministry of Munitions sent Cornishman, Henry F. Collins, to inspect the Luganure Mines in order to report whether these were vital to the war effort and therefore worthy of reworking with capital aid. The Wynne’s small dressing plant formed a part of his report. Collins, the son of mining engineer, J. H. Collins, noted the plant to have been powered by a horizontal suction gas engine and producer which had possibly been manufactured by Cornish firm, Tangye’s of Birmingham.

He recorded the maximum capacity of the plant to have been 15 tons per day and about 75 tons per week, the yield being about 12 cwts of dressed galena and 1¼ tons of blende per week. He considered that better results could have been obtained by a much more extensive picking out of waste rock that existed in large quantities in the old MCI dumps. He also observed that the jigs were underloaded.

Collins concluded his report by stating that reopening the Luganure Mines was unlikely to tempt investors, but he noted,

“From the point of view of developing Home Mineral Resources, the government may legitimately assume risk and invest capital to establish a dead industry in a deserted countryside to produce a raw material vital to the war effort.”

The Ministry of Munitions, however, declined to invest in the Luganure Mines, and the White Rock plant made a loss of £19 on the four months prior to November 1919. The Wynne’s mining operations were continually hampered by bad air and flooding due to a lack of proper machinery.

Mining ceased and the treatment plant closed in 1921 due to the falling price of lead and zinc concentrates in the post war period and the chaos unleashed during the Irish War of Independence, making it impossible to procure explosives for blasting. Collins was probably the last Cornishman to have any involvement with the Luganure Mines.

The Irish-Canadian Wicklow Mining Company Ltd.

In 1943, following a small grant by Mianraí Teoranta, some exploratory work was undertaken by John B. Wynne in Glendasan. A sum of £25,000 was required to develop new workings as the MCI era ones were in poor condition and reopening these was deemed unviable, but the State refused capital aid for this venture.

Spurred on by high lead and zinc prices in the post-WW2 years, mining resumed once more in May 1950 and the Wicklow Mining Company Ltd. was incorporated by seven local investors. Work centred mainly on the Moll Doyle and Foxrock Lodes in Glendasan.

Initially, the company rented a flotation plant from Mianraí Teoranta at Avoca, the ore to be milled being conveyed daily by truck, which ate into the company’s profit margin. A gravity mill capable of treating 50 tons of ore a day was erected at Foxrock to treat the ore in 1953. Wynne tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain financial aid from the Industrial Development Authority to modernise and more fully develop the mines, as well as building a much needed froth flotation plant in Glendasan.

In 1956, the Wicklow Mining Company Canada was created to lease the mining rights from the Wicklow Mining Company Ireland in order to solve the financial crisis that threatened to halt operations. A subsidiary, the St Kevin’s Lead and Zinc Mine Ltd., was set up to do the mining.

It was a short-lived affair. The Canadians found that the prospects that had induced them to take on the mine proved to be less favourable than anticipated; tunnelling costs were far higher than expected and the ore reserves that had been established were not sufficient for mining on the scale envisaged. A fatal accident sounded the death knell for the company in 1957.

In the early-1860s, the government finally stepped in with an offer of a £10,000 loan which financed an unsuccessful drilling venture centred on New Hero. In 1963 the Wicklow Mining Company met for the last time and an auction of materials was carried out in about 1965. The Wicklow Mining Company was finally removed from the companies register in 1975, ending a long history of lead mining in the area.

The Cornish at Luganure

There was never a discrete Cornish community in the Seven Churches area; indeed, the numbers living there were far smaller than at Avoca. Moreover, they were widely dispersed; some lived in the well-built housing provided by the company on the mines, while others lived at Seven Churches and Annamoe. Few lived at Laragh.

This was just as well, because the villages of Rathdrum and Laragh were less than salubrious, with the former described as full of pools of filthy water and dung heaps near entrance doorways. “If King Cholera should unfortunately visit our shores,” opined a letter writer dubbing himself ‘Prevention,’ in the Wicklow News-Letter in September in 1865, “he would make this village one of his resting places.” In September 1866, cholera broke out in the area. By October there had been 35 fatal cases in Wicklow and the unsanitary condition of Laragh caused alarm:

“The whole village of Laragh, situate in the townland of Brockagh, is in a filthy and unwholesome condition as to be a nuisance and injurious to the health of the occupiers of the houses thereat.”

Entertainment was likely to have been rather limited, although events such as the celebration of the Prince of Wales’s wedding in 1863, when Brockagh Mountain was said to have been illuminated with tar barrels sent up by Mr Jordan of the Royal Hotel, were undoubtedly enjoyed.

There was no Methodist chapel in the vicinity of the mines, so most of the Cornish would have worshipped at the Church of Ireland, if at all. Indeed, the Protestant mineworkers contributed to the building costs of St. John’s Church in Laragh in 1843.

In common with Avoca, the neighbourhood was rough, and not all of the population was honest. In 1874, a number of shopkeepers near the Luganure Mines were fined for keeping faulty weights and measures, and the court spoke in strong terms of the conduct of shopkeepers “who would thus treat the poor miners by cheating them out of their just rights when purchasing meal, flour etc.”.

Moreover, fighting and rioting caused by drunkenness often broke out, much of which took place on the Sabbath. Many of the mineworkers made their way to the public houses of Rathdrum where they were noted, “to drink and sing songs up to a late hour of night, then come into the streets and raise rows and fights.”

In 1862, at the height of the mines’ success, a constable stationed at Laragh remarked that “the people were more like savages than men”, and his colleague swore that he never saw Laragh and its neighbourhood in so frightful a state of fighting and drunkenness as it was on the Saturday and Sunday.

There was even a case of men employed by the MCI to cart ore from the mines imbibing rather too freely in whiskey while resting their horses in Rathdrum. Being incapacitated, they caused one of the cars to leave the road and plunge down a bank.

In answer to the scourge of intemperance, the Good Templars Society began to flourish in Wicklow, which was supported by the Cornish, many of whom were teetotal Methodists. Indeed, at Avoca, a Good Templars soiree in November 1874 was presided over by Captain Henry Trezise and Brother Barkla, with Miss Trezise playing the harmonium.

But the organisation did not meet with the approval of everyone, with accusations of it being a secret society, or what one angry letter writer called, ‘a national disgrace’: “The Scotch, the English, the all conquering German drink more than the poor Irishman, and yet we scarcely hear one word spoken in depreciation of the habits and customs of those countries.”

But riotous behaviour fuelled by drink became so bad at Brockagh in the fall of 1876, especially at the public house belonging to Richard Mahon who was a notorious drunkard himself (and who had his license taken away), that Magistrate Frizell urged his fellow magistrates at the Rathdrum Petty Sessions to adopt stringent measures for its suppression. Shortly afterwards, a piece was published in the Wicklow News-Letter which got in a snide dig at the Luganure Cornish management, which of course, did not condone drunkenness among its workforce:

“…farewell my merry miners, with your neat cottages who despise beer and whiskey and calls for your bottle of wine o’ pay-nights…”

As in their efforts to provide good housing for their workforce, the company also manifested its benign paternalism with its regard to the provision of education, a move much-supported by the small Cornish community.

“No man would not be found to contend that property had not its duties as well as its rights. No duty was more important to be performed by those who desired to benefit their fellow-creatures than to improve their material and mental position. We do the one by giving a fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work, and the other by providing schools and the means of education for the children of our workmen.“

MCI Chairman, January 1863

The National School system was established in Ireland in 1831, and St. Kevin’s School, the earliest non-denominational school in the area, was founded in 1831 in Brockagh.

It was built with donations from the poor of the area plus £1 10s from Henry Grattan and £1 each from Laurence Byrne, Cronybyrne and Richard Purdy of the MCI. The building was plastered and thatched with three windows and measured 40’ by 16’. It joined two pre-existing schools in the area that catered for Catholic children.

Among the Church of Ireland signatories to the June 1832 application was Cornishman, John Andrewartha, who was born in Gwinear parish in 1799 and married an Irish woman named Annie O’Neill. The couple had at least five children at Seven Churches before Andrewartha took his family back to his native parish in Cornwall in the mid-1850s. Another was Abraham Halman (Holman) who was probably Cornish too.

Elementary books with Catholic and Protestant Catechisms were supplied by the parents. The hours were 9am-4pm, six days a week. Attendance was 40 boys and 40 girls in the winter, and 30 boys and 20 girls in the summer. Up to 90 children could be accommodated. Take-up was slow at first, but improved after the schoolroom was made more comfortable through the provision of desks and chairs. Students paid 1-2s per quarter. The school got off to a rocky start, opening and closing several times, and the standard of teaching left much to be desired.

In about 1866, St Kevin’s female National School was opened with an emphasis on music, and attained an average attendance of 64.

Several of the Cornish mineworkers children received their education at St Kevin’s Schools. This included Edwin Lemin, who was born at Glendalough in 1875. He entered the boy’s school aged three. Edwin was the son of Cornish miner John Lemin of St Blazey and his wife, Maria Prowse, whom he had met and married in 1857 while working at a silver-lead mine in Christow, Devon. Following the death of his mother in 1878, Edwin was eventually sent to live with his paternal grandparents at Polgooth near St Austell.

Another family with Cornish links was called Caddy. William Henry Caddy, the son of James Caddy of St Breock Cornwall, and his Cornish wife, Grace Charles, was born in Ferrey Foreyon, Cumberland, England. He married Frances Jolly and between 1867-1871 the family lived near Annamoe, before moving to Ulverston in Lancashire, illustrating the highly mobile nature of the Cornish (and Irish) mining population. Their son Samuel J. Caddy was enrolled at St Kevin’s School in October 1878. Interestingly, there is a Caddy’s Adit on the Luganure Mines at Glendasan, probably named after William Henry.

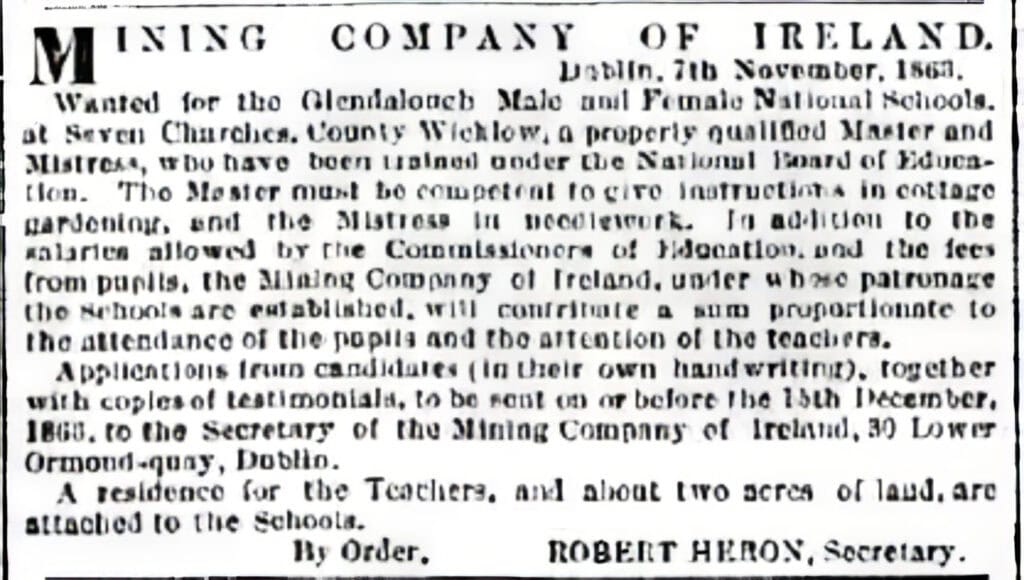

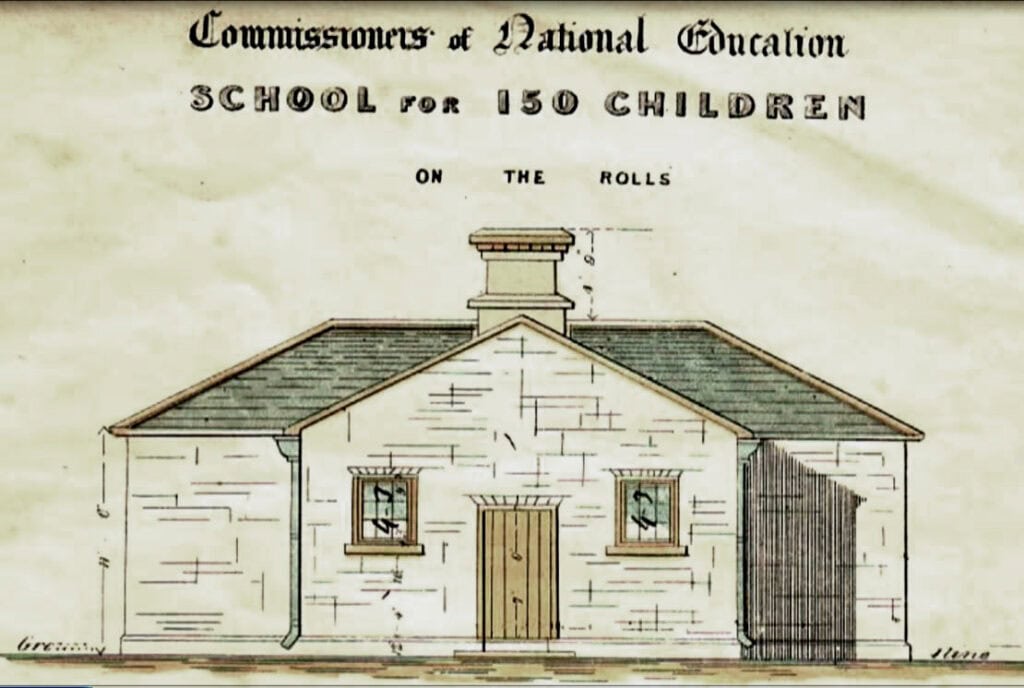

By the mid-nineteenth century the mines were booming and population had grown rapidly. So, in 1862 the Commissioners of National Education granted the sum of £327 for the purpose of erecting schools at the Seven Churches, able to accommodate 150 children. The MCI agreed with the Commissioners of National Education to establish a school in the most central part of the Seven Churches. It was argued that St. Kevin’s was too far away and the only other was the Laragh school run by the Church Education Society.

The application to build the school house was made by Captain Clemes in April 1864. The provision of the new school was not without its detractors and he argued vociferously as to the relative merits of it, as he did not believe it conflicted with St. Kevin’s school.

A plot at Derrybawn was made available by the MCI who pledged to contribute one-third of the building costs. The number of probable students, largely the children of the company’s mineworkers, was 142, but it was thought that this would probably increase. The Board granted £204 out of the £306 for the total construction costs, and the salary for Martin Quinn aged 28, from Galway Model School, who was the successful applicant of the above advertisement for position of master of the Boy’s School.

Quinn taught at the school until the unforeseen migration of the MCI workforce, largely to the iron mines of Cumberland, resulted in an average of around 20-25 children. It was struck of the rolls in 1872 and the MCI refunded the Board of Works £327 10s and handed over the lease. The schoolhouse is now a private residence.

In 1890 largely due to the closure of the lead mines and subsequent migration of miners and their families, St Kevin’s boy’s school was permanently closed and amalgamated with St. Kevin’s female school.

Industrial Legacy

The mining activity in the valleys of Glendalough and Glendasan has left a rich industrial legacy. The dressing floors in particular offer the finest example of nineteenth century lead ore dressing methods and technology in all of Ireland.

Further Reading on the Luganure Mines

Wicklow County Council (ed. Martin Critchley) (2008) Exploring the Mining Heritage of County Wicklow. Download it here

Schwartz S P and Critchley, M F (2012) ‘The Lead Ore Dressing floors at Glendalough and Glendasan, County Wicklow, 1825-1923: A History, Survey and Interpretation of Extant Remains’, Journal of the Mining Heritage Trust of Ireland 12, 5-52.

Visit the Luganure Mines

Under the aegis of the EU-funded InterReg transnational project Metal Links: Forging Communities Together (2011-2014), mine sites in both valleys were recorded and the dressing floors were surveyed. Interpretation boards were added at key sites including Van Diemen’s Land, and the Glendalough and Glendasan Dressing Floors.

The Glendasan dressing floor has recently undergone consolidation works to help to protect its fragile archaeology. All sites lie within the Wicklow Mountains National Park which maintains a fine network of walker’s pathways which pass close to much of the important archaeology.

The Miners’ Way is a a way-marked trail with start/finish points in the Glendasan and Glenmalure valleys. It is approx. 19km in length and takes in the remains of old mine workings, processing plants and touches upon the rich mining heritage of the area.

Watch the aerial film in 4K showcasing the relict mining landscapes of the Wicklow Mountains (and Avoca mines):

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2025.